“Don’t do it, Jimmy. Your presence will only dignify his position.” This was the advice Norman Podhoretz gave to his friend James Baldwin when he was invited in late 1962 to debate arch-segregationist James Jackson Kilpatrick on the NBC talk show The Open Mind. Baldwin did not heed Podhoretz’s advice. Although Baldwin did not relish the opportunity to sit across a table from Kilpatrick, he felt duty-bound to do so and his example can teach us something valuable about the nature of our duty to confront racism in our own time.

Kilpatrick was, in the words of his biographer William Hustwit, the country’s leading “salesman for segregation.” As editor of the Richmond News Leader, he had established himself as the chief propagandist for the state of Virginia’s “massive resistance” campaign in response to court-ordered school desegregation. In addition to spreading his gospel of segregation in the columns of the News Leader, Kilpatrick used the issue as a lever to catapult himself into the national spotlight. He wrote books on the subject and he penned articles about it for leading conservative publications including National Review and Human Events. He also appeared on television often to participate in interviews and debates. Prior to his encounter with Baldwin, Kilpatrick had twice debated Martin Luther King Jr., and he found himself a frequent guest lecturer and debater on college campuses across the country. About a year after his encounter with Baldwin, Kilpatrick would write to his close friend and collaborator William F. Buckley Jr., “I’m off to Bryn Mawr-Haverford tomorrow, to do battle with James Farmer of CORE (and six other colored gen’mun) on questions of civil rights. It’s a tough way to make a living.” By the time he met Baldwin, Kilpatrick was well on his way to earning the nickname Buckley would give him later: “Number One,” which signified, Buckley explained, Kilpatrick’s status as “one of the primary editorialists on our side of the fence.”

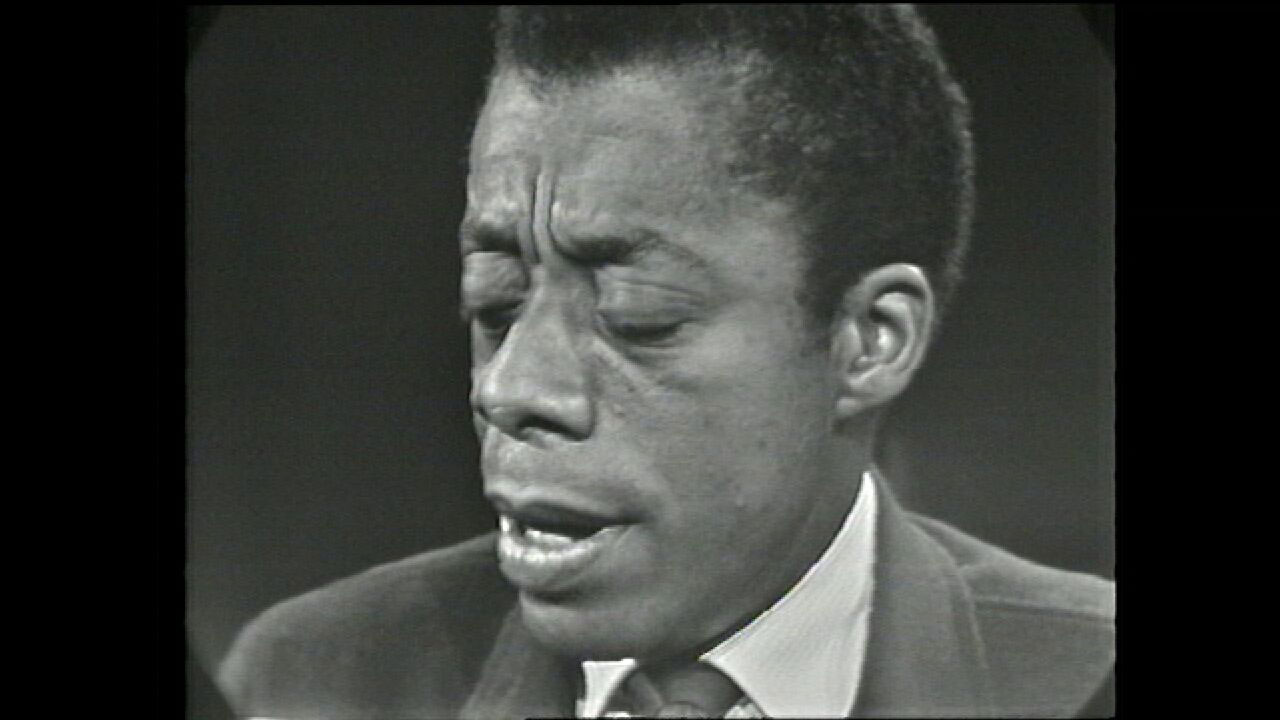

Baldwin, for his part, had spent the decade and a half prior to his meeting with Kilpatrick climbing a very different ladder. After ascending the ranks first as a literary critic, short story writer, and essayist in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Baldwin began to garner significant literary attention with his first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, which was published in 1953. His 1955 collection, Notes of a Native Son, established him as a serious essayist and his 1956 novel, Giovanni’s Room, proved to be an international sensation. In the years prior to his encounter with Kilpatrick, Baldwin traveled through the South to report on the burgeoning civil rights movement and many of his essays based on his experiences there were collected in Nobody Knows My Name (1961). His bestselling third novel, Another Country, was published in 1962.

By the time he met Baldwin, Kilpatrick was well on his way to earning the nickname Buckley would give him later: “Number One,” which signified, Buckley explained, Kilpatrick’s status as “one of the primary editorialists on our side of the fence.”

In the weeks leading up to his meeting with Kilpatrick, Baldwin was working out the contours of his moral and political philosophy in a work that would eventually become his most famous. The project, which was due to be published in The New Yorker in November 1962, was called “Down at the Cross” by Baldwin, retitled “Letter from a Region in My Mind” by the editors at The New Yorker, and eventually published (along with a short piece) as “Down at the Cross: A Letter from a Region in My Mind” in the book, The Fire Next Time. The long essay was a tour-de-force in which Baldwin blended autobiographical writing with reportage, moral philosophy, and political theory. In it, Baldwin used his own experiences growing up in Harlem in the 1930s, his encounters with the Nation of Islam (NOI) in the early 1960s, and general reflections on the “moral history” of the West as the basis for complex meditations on the relationship between identity and power. Baldwin’s essay culminated in a bold call to liberate ourselves from the delusions inspired by “totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, [and] nations” and to focus on what really matters: the dignity of each human being.

• • •

The last time Baldwin had appeared on The Open Mind, in April 1961, he had occasion to work out some of the ideas that would end up in his New Yorker piece. On the program with Baldwin that night was C. Eric Lincoln, a philosopher who had just published a book on the NOI; the black conservative newspaper columnist George Schuyler; and none other than Malcolm X, who was widely considered the NOI’s second-in-command. It is worthwhile to consider this 1961 appearance on The Open Mind because Baldwin’s message that night—particularly in response to Malcolm—would have a direct bearing on how he viewed Kilpatrick.

During the first several minutes of the discussion, Baldwin sat back in silence as Open Mind host Eric Goldman queried his guests on the nature of the “Black Muslim program” while Schuyler attacked the NOI as a delusional and racist organization. After some back and forth with his other guests about NOI doctrines, Goldman invited Baldwin to join the conversation. What, Goldman asked, was his “understanding of the purposes of the movement?” The “Muslim movement,” Baldwin responded, ought to be understood in terms of “power,” “morality,” and “identity.” What the NOI promised its followers, he explained, was the acquisition of power in exchange for the acceptance of its separatist and supremacist morality. The experience of injustice that marked the lives of African Americans, Baldwin argued, was what provided the NOI with fertile ground in which to grow. When an NOI minister tells a would-be recruit in one of the nation’s ghettoes or prisons that he is being oppressed, Baldwin said, the minister has “all the evidence” on his side.

This comment caused Schuyler to direct his indignation, for the moment, from Malcolm to Baldwin. He thought Baldwin’s suggestion that “all the evidence” was on the side of the NOI was absurd and he worried that such concessions could be seen as justifications for their anti-white propaganda. Baldwin actually found himself in some agreement with Schuyler on the issue of the NOI’s racism. The NOI, Baldwin had said earlier in the conversation, had a great deal in common with the Southern segregationists. What the NOI had done, Baldwin argued, is simply taken the ideology of white supremacy, reversed the racial power positions, and dressed it up in their theological and moral doctrines. As Baldwin explained it that night, “What the Muslim movement is doing is simply taking the equipment or the history really of white people with Negroes and turning [it] against white people.” Baldwin could not have declared any more clearly how deeply he was opposed to this approach. The NOI may be able to make people feel more empowered, but their doctrines were a recipe, on Baldwin’s view, for moral disaster. Black Muslims should remember, he insisted, that white supremacy had “done more to destroy white men in this country … than it has done to destroy the Negro.” Baldwin made this point while acknowledging the obscene history of violence against people of color in the United States. This violence had destroyed the bodies of many, but NOI doctrines promised to destroy the souls of many more. From Baldwin’s point of view, there had to be a better way.

Baldwin’s nuanced position on the NOI—his simultaneous concession of the truth of their diagnosis along with his condemnation of their prescription—perplexed his white liberal host. “Mr. Baldwin,” Goldman said, “now you confuse me. One can have two aims if one is a Negro…”: integration or separation. The NOI was clearly for separation; what was Baldwin’s view? Baldwin shrank back in frustration and was silent for several minutes. Goldman’s response was, unfortunately, the typical one for “white liberals,” who Baldwin assailed about as often as any group. In the face of the NOI, liberals like Goldman tended to dwell on details and asked all of the wrong questions. During the Open Mind episode, Goldman obsessed over the minute specifics of the NOI’s economic and political program.

Just how would this separate economy work? Did the NOI intend to use violence to accomplish its goals? For Baldwin, these questions missed the forest for the trees. The specifics of what the NOI was up to, Baldwin saw—and his host clearly did not—were really of minor importance in comparison to the details of American life that made the rise of the NOI possible in the first place. How is it, Baldwin wondered, that such a peculiar group could gain any sort of a foothold in our society? We cultivated the ground in which this movement grew. What can the NOI, Baldwin wanted folks like Goldman to ask, reveal to me about my role in our racial nightmare?

The question, Baldwin told Goldman, is whether white people are ready to take responsibility for the part they have played in the rise of groups like the Nation of Islam. The despair that the Nation of Islam exploited was real and until the entire society was ready to do something about the roots of that despair, there was little cause for hope.

When he came back into the conversation, Baldwin confronted Goldman on these matters after the host admitted that what he—and presumably his mostly white audience—really wanted “to find out is whether the Muslim movement does hate me or not, and whether it proposes to use force to satisfy that hatred.” Baldwin could not contain his disappointment with the narrowness of Goldman’s view. “It is not important,” he told Goldman, whether they hate you or not; “that is not at all the question … that’s irrelevant.” The question, Baldwin told Goldman, is whether white people are ready to take responsibility for the part they have played in the rise of groups like the NOI. The despair that the NOI exploited was real and until the entire society was ready to do something about the roots of that despair, there was little cause for hope.

In the weeks just prior to Baldwin’s encounter with Kilpatrick, the “Battle at Ole Miss” marked the latest front in the civil rights revolution. The battle was sparked by the attempts of a black Air Force veteran named James Meredith to register for classes at the segregated University of Mississippi (Ole Miss). Meredith’s attempts to enroll at the institution, which had been authorized by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, were blocked by Governor Ross Barnett who called on “every public official and private citizen” in the state to resist the “moral degradation” of integration. After Barnett blocked Meredith’s attempts to enter Ole Miss to register on two occasions, President Kennedy federalized the Mississippi National Guard and sent Meredith—accompanied by Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach and four hundred federal marshals—back to campus. As Attorney General Robert Kennedy and Gov. Barnett attempted to bargain behind the scenes, a mob of whites gathered on campus. Former Army Major General Edwin Walker, who had been relieved of his command for attempting to indoctrinate troops with far-right political ideas, had put out a call for 10,000 volunteers to descend upon the state in order to resist integration.

On the evening of September 30, the Ole Miss campus was racked by violence as protesters and marshals clashed in a sea of bricks, bats, tear gas, and gunfire. At one point in the melee an Ole Miss student who had been sent to negotiate with the marshals, reported to the mob: “Here’s the deal. The marshals will quit using tear gas if we’ll stop throwing rocks and bricks.” In response, someone shouted: “Give us the nigger and we’ll quit.” Walker—who had become a hero to many on the American right wing—stood tall in his Stetson cowboy hat and urged the protesters to keep fighting the tyrannical Kennedy administration.

Meanwhile, Gov. Barnett huddled with advisors in Jackson, including leaders from the racist Citizens’ Council, which had been aptly described by one journalist as the “uptown Klan.” In his conversations with members of the Kennedy administration, it was clear that Barnett was looking for a way to diffuse the situation without losing face with the most ardent of his segregationist supporters. Kennedy decided he had waited long enough for Gov. Barnett to pull off this feat so he ordered federal troops stationed in Memphis to quell what one marshal called the “armed insurrection” at Ole Miss. When the dust settled, two people were dead, more than 300 were injured, and Kennedy ordered General Walker to be committed for a 90-day psychiatric evaluation.

Kilpatrick was in Mississippi to witness “The Battle at Ole Miss.” Reporting from campus before all hell broke loose, Kilpatrick waxed philosophical about the tragic “struggle” between two sides convinced that their point of view was the right one. After Kilpatrick “surveyed the mood on campus” and “predicted violence,” he made his way to the capital in Jackson, where he met with Gov. Barnett and Citizens’ Council leader William J. Simmons, who Kilpatrick counted as a friend and sometime-collaborator. The two segregationists looked on with pride as a mob gathered around the Governor’s mansion to protect Barnett from federal marshals. “They won’t give up,” Simmons told Kilpatrick. “They won’t ever give up. They’re the finest people on earth.” By the time they did indeed give up, Kilpatrick was back in Oxford to see several protesters—including General Walker—arrested.

• • •

As Baldwin and Kilpatrick settled into their seats on the set of The Open Mind, the tension in the air must have been palpable. The recent events in Mississippi were undoubtedly on their minds as were events in Cuba, where Soviet nuclear missiles had been discovered just days before. In addition to these general reasons for tension, Baldwin and Kilpatrick had more personal reasons as well. Not only had Kilpatrick recently published The Southern Case for School Segregation, but to add insult to injury, he had just tried his hand at literary criticism with a scathing review of Baldwin’s latest novel, Another Country. The stage was set for an intellectual brawl.

As Kilpatrick and Baldwin sat back and lit up their cigarettes, they likely sized each other up from across the table between them. Kilpatrick looked through his horn-rimmed glasses at a small man in his late thirties with large “frog eyes” and a pronounced gap between his two front teeth. Baldwin looked back at a pale man of average height and build, with a weak chin and a receding hairline. Between them sat Goldman, a ruddy-faced historian from Princeton University, who looked and acted the part of the liberal professor.

After Goldman welcomed the television audience, Baldwin mentioned the moral “bankruptcy” manifested in recent events in Mississippi and then went straight for Kilpatrick’s jugular. “You may think that there’s a distinction between a man who writes a book like your book,” he said to Kilpatrick, “and the people who castrate Negroes in the streets. But from my point of view, it is men like you who write those books who are responsible for those mobs.” With this opening statement, Baldwin was declaring his primary reason for agreeing to appear with Kilpatrick: He was there to tell the world that language has power, some men were abusing that power, and it was his duty to use the weapon of language to fight back.

Over the years, Baldwin had shown remarkable empathy for what we might call “reflexive racists,” the men and women who had been raised to believe in racial hierarchy and hardly devoted a moment’s thought to why they held these views. These unthinking racists, he argued, were among white supremacy’s greatest victims. These folks had been taught to believe that their whiteness was their primary source of power and that they ought, therefore, to do all they can to maintain the racial caste system. Baldwin thought that the reliance on one’s racial identity as a source of power was nothing short of disastrous. He had made this much clear in his reflections on the NOI and the doctrine of white supremacy was every bit as worthy of condemnation. In both cases, Baldwin argued, the reliance on race as a lever for power was rooted in despair and delusion. Faced with a feeling of powerlessness, the average white person clings to the delusion that his whiteness has moral value. This idea did not come down from God on high; it was preached by men like Kilpatrick for generations. The doctrine of white supremacy had been created by particular human beings for particular reasons and Baldwin was about to expose Kilpatrick for what he really was.

Over the course of their hour together, Baldwin played the role of cross-examining prosecutor while Kilpatrick attempted to defend his white supremacist views. On the surface, the core of Kilpatrick’s case went something like this. White people are intellectually superior to people of color. This superiority is rooted in both “hereditary characteristics” and “characteristics of environment.” White intellectual superiority led to greater white contributions to “Western values” (e.g., in “law, philosophy, art, morality, and architecture”) and white people are “better equipped in every way to preserve those values.” Racial apartheid and white supremacy were justified, Kilpatrick concluded, in order to “preserve whatever it was from civilization that was worth preserving.”

As Baldwin interrogated Kilpatrick, he was interested in doing more than simply refuting the Southerner’s “case for segregation.” What interested Baldwin was what was hidden beneath the surface of that case. “The question of color,” he had written in the introduction to Nobody Knows My Name, “operates to hide the graver questions of self.” His task was to reveal not only why Kilpatrick was wrong on the question of color, but also to expose what Kilpatrick’s views revealed about the state of his soul and the souls of all those in thrall to the racial mythology he peddled on a daily basis.

On the question of color, Baldwin pushed Kilpatrick to produce evidence to support his claims of white superiority. When Kilpatrick listed the names of several racist pseudo-scientists, Baldwin was unimpressed. What had these men proven? Kilpatrick argued that they had proven white men had made superior contributions to “Western values.” Suppose these men really did establish a meaningful way to differentiate and measure these contributions on the basis of race, Baldwin said, what would this demonstrate? For one thing, Baldwin insisted, the racial categories would be constructed, not real. For another thing, Baldwin posited that the differences they were able to identify probably had a great deal more to do with “power” than they did with “innate inferiority.” The “characteristics of environment” that had done so much to shape racial disparities in academic and social outcomes were the products of power differentials, not nature. “The reason I can’t be President now,” Baldwin told Kilpatrick, “is not because I’m inferior to Bobby Kennedy. It is because the fact I was a slave once in this country is written on my skin.”

But what about those “Western values”? What if Kilpatrick conceded to Baldwin that racial hierarchy was more a product of power than it was innate inferiority? Could he not still make the case that white supremacy might be justified to “preserve whatever it was from civilization that was worth preserving”? Baldwin did not think so. In the first place, Baldwin said that even if one accepted Kilpatrick’s theory of racial hierarchy, “you would still have no right to do what you do. Maybe I am inferior to you, let us say, but I’m still a human being.”

Furthermore—and perhaps even more damning to Kilpatrick’s case— Baldwin contended that white supremacists were doing far more to undermine “Western values” than to protect them. Kilpatrick’s “very profound error,” Baldwin argued, was to assume that “we have two civilizations” and that the only way Kilpatrick could protect his civilization was to exclude people of color from it. “Don’t you see that if there is an American civilization,” Baldwin asked Kilpatrick, “what happens to me in it is happening to you?” Men like Kilpatrick claimed to be “protecting Western values,” but in fact they were “destroying them.” If “you really take seriously,” Baldwin said to Kilpatrick, such things as “the Bill of Rights” and “the Western journey,” then you are under the obligation … the necessity… the duty” to include all people in the best this journey has to offer.

Baldwin’s argument on this issue was nuanced. His point was not only that white supremacy undermines the dignity of its victims. This would have been damning enough, but there was more to his case than that. In addition, Baldwin wanted Kilpatrick—and all those watching—to see that white supremacy was undermining the dignity of its supposed beneficiaries. Kilpatrick and his fellow race peddlers were in the business of propagating a false sense of identity to those desperate to find power in a world in which they often felt powerless. This was the “grave question of self ” that rested behind the “question of color” for the supposed beneficiaries of white supremacy. Kilpatrick and NOI leader Elijah Muhammad were, for Baldwin, two sides of the same coin. Folks who accepted their messages of racial pride may have found themselves feeling more powerful, but that power came at the price of their dignity. This was far too high a price to pay.

As Baldwin interrogated Kilpatrick, he was interested in doing more than simply refuting the Southerner’s “case for segregation.” What interested Baldwin was what was hidden beneath the surface of that case. “The question of color,” he had written in the introduction to Nobody Knows My Name, “operates to hide the graver questions of self.” His task was to reveal not only why Kilpatrick was wrong on the question of color, but also to expose what Kilpatrick’s views revealed about the state of his soul and the souls of all those in thrall to the racial mythology he peddled on a daily basis.

For Baldwin, it was obvious enough why “the poor white people of the South”—“the porter, the farmer, the sharecropper”—might be tempted by white supremacy’s promise of power. But what about a man like Kilpatrick? What grave “question of self ” was lurking behind his obsession with the “question of color”? For Baldwin, the answer had to do with self-interest and fear. The matter of self-interest was straightforward enough. The primary thing Kilpatrick wanted to conserve was his own career and there was a strong market for his genteel brand of racism.

The fear that haunted Kilpatrick’s sense of self was a bit more complex. As Baldwin had explained a few years earlier in a piece on the Southern writer William Faulkner, “real change implies the breakup of the world as one has always known it, the loss of all that gave one an identity, the end of safety.” The black man had moved out of his place, a place that had served as “a fixed star” and an “immovable pillar” in the white man’s world. This, Baldwin acknowledged, must have been disorienting and “terrifying.” If he is no longer there–where he belongs–then where does that leave me? If he is not who I thought he was, then who am I? The breakdown of the illusion of race supremacy forced a man like Kilpatrick to confront many realities that must have frightened him to his core.

“The real terror,” Baldwin explained, was “that you have described me for so long” and “now I can describe you. That is what you are afraid of.”

But there was more to Kilpatrick’s fear than this. “The real terror,” Baldwin explained, was “that you have described me for so long” and “now I can describe you. That is what you are afraid of.” Whites like Kilpatrick had worked so hard over the years to create and perpetuate mythologies to hold together the fortress of white supremacy and now those mythologies were under attack on a scale that was without precedent in American history. The civil rights revolution promised to bring about not only a radical new chapter of self- definition for marginalized people, but also it threatened to empower oppressed people to tell the stories of their oppressors. As Baldwin had explained early in his conversation with Kilpatrick: “You think I see you as you see you. But I don’t. I see you another way …. My life has been in your hands for so long, that I’ve had to watch you.” Baldwin and his brothers and sisters had been forced by circumstances to watch men like Kilpatrick closely for a very long time and with liberation would come greater opportunities to describe what they’d seen. For men like Kilpatrick, this must have been a “real terror” indeed.

• • •

Baldwin’s encounter with Kilpatrick over half a century ago can be instructive for us today. Contemporary American democratic life is haunted by many of the same demons that were in Baldwin’s midst. Although Baldwin and his contemporaries did a great deal to batter the fortress of white supremacy, it still stands and we are reminded of its strength every day. White nationalist authoritarianism is resurgent in American politics. The “color line” is still evident in so many aspects of our social, political, and economic lives. Black people are more likely to be incarcerated, sick, and victims of police brutality and less likely to receive adequate education, health care, or economic opportunity. NOI ministers, Baldwin might say, still have plenty of evidence on their side.

In the midst of our racial nightmare, marginalized people and their allies are confronted day in and day out with plenty of Kilpatrick-like characters. The Kilpatricks among us are not just the intellectuals and pundits who apologize for explicitly white supremacist politicians like Donald Trump. The Kilpatricks among us also pop up on our television screens and on our campuses in much more subtle forms. With smooth rhetoric, dog whistles, and coded language, our Kilpatricks know that they can get to the same ends Trump seeks without using his boorish means. They recognize one need not build a wall to exclude “others”; theirs is a politics of exclusion far more insidious and perhaps therefore more dangerous.

So what might Baldwin have us do in the face of our Kilpatricks? One thing Baldwin would insist upon is that we confront them and that when we confront them we seek to get beneath the surface of things to reveal what is really animating their moral lives. It is precisely because the arguments of our Kilpatricks are so insidious that it is incumbent upon each of us to expose the “graver questions of self ” that lurk behind their exclusionary politics. All of us, Baldwin would remind us, hide behind masks of power because we do not think we can survive without them. But love, in its deepest sense, requires to help one another remove those masks and confront our true selves.

This sort of existential detective work is also what Baldwin would prescribe for our dealings with the Goldmans among us. When Goldman was confronted with Malcolm X and James Kilpatrick, he stayed fixated on the surface of things. Just what was it that Malcolm proposed to do? Just what did Kilpatrick really think of black people? These questions, Baldwin insisted, were worse than unhelpful; they were ultimately harmful to the quest for racial justice. In both cases, Goldman was—implicitly—offering himself and his viewers invitations to maintain their innocence. Yes, things are bad for black people in this country, Baldwin imagined a typical viewer thinking, but that Malcolm X has taken things too far. I am disgusted, this same viewer might have thought, by segregationists like Kilpatrick. Have not we moved on from such reactionary views?

It is precisely because the arguments of our Kilpatricks are so insidious that it is incumbent upon each of us to expose the “graver questions of self ” that lurk behind their exclusionary politics. All of us, Baldwin would remind us, hide behind masks of power because we do not think we can survive without them. But love, in its deepest sense, requires to help one another remove those masks and confront our true selves.

Both of these responses allow the viewer to place himself outside of the problem. Baldwin thought it was imperative that we stop engaging moral questions in this way. The moment we start feeling self-righteous, Baldwin counseled, we had better start examining ourselves a bit closer. The vices of the Kilpatricks, the Goldmans, and the Malcolms were but manifestations of a deeper sickness of the American soul. So it was then, and so it is now.

When we are confronted by those “respectable racists” who, like Kilpatrick, are willing to defend white supremacy with smooth rhetoric and measured tones, it is tempting to turn away and, as Podhoretz put it many decades ago, refuse to “dignify” them with a response. When we do respond, we all too often do so with soothing indignation that merely bounces off the walls of our echo chambers. But this, Baldwin’s example teaches us, is an abdication of our duty. It is men like Kilpatrick, as he said that night, who bear the greatest responsibility for the racial nightmare that haunts this country and it is our obligation to expose this fact. The reason Baldwin could not heed Podhoretz’s advice is simple and profound: our duty in the face of racism is not to turn away, but to engage it, expose it, and defeat it. As we do so, we should follow Baldwin’s example and not Goldman’s because Baldwin saw so clearly what Goldman clearly did not see at all: that “the question of color operates to hide graver questions of self.” In the hearts of the racist demagogues, their apologists, and even some of their critics, there are many secrets. Our job is to expose those secrets. Our moral lives depend on it, and so do theirs.

Note: Elements of this piece are adapted and expanded from my forthcoming book, The Fire is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate Over Race in America (Princeton University Press, forthcoming, 2019).