Connecting Flights

Under American skies

May 24, 2023

1.

Joe, though impetuous, was quick-witted and dependable. Frank, more serious-minded, was inclined to think out a situation before taking action. They worked well together.

—Franklin W. Dixon, The Shore Road Mystery

The wording varied from book to book—“Frank, who was a year older than his brother and less impetuous…” (The House on the Cliff); “Dark-haired, eighteen-year-old Frank, and blond impetuous Joe, a year younger . . .” (The Secret of the Old Mill). But the idea was always the same in the original Hardy Boys series, young adult novels by Franklin W. Dixon published over a span of fifty-two years beginning in 1927: Frank and Joe Hardy had qualities that complemented each other, and their differences made them a good team when it came to their shared passion, which was solving mysteries.

For my tenth birthday, in 1973, an older cousin gave me a copy of the fifth book in the series, Hunting for Hidden Gold. Before that, and for a number of years afterward, my reading consisted mainly of comics, but I liked Hunting for Hidden Gold well enough to seek out other titles in the series. Those mysteries were the first novels I read.

2.

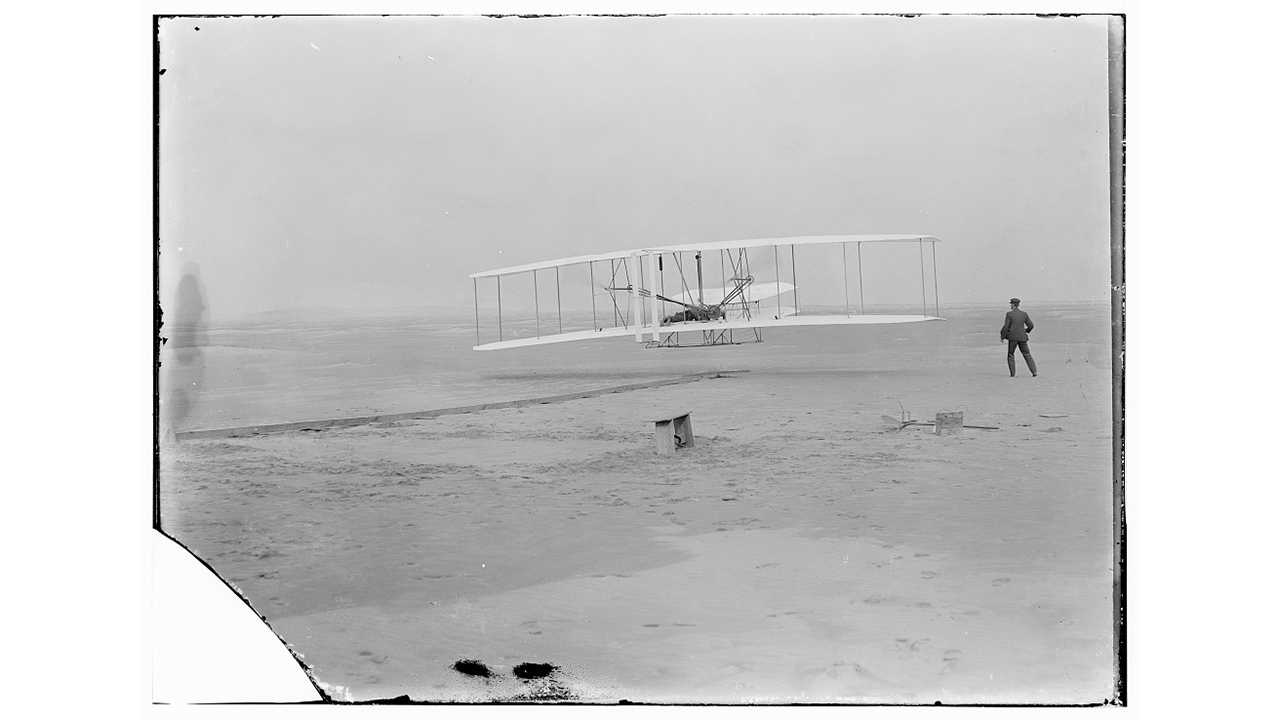

From The Wright Brothers, by David McCullough: Wilbur, the older brother, “was more serious by nature, more studious and reflective. His memory of what he had seen and heard, and so much that he read, was astonishing. ‘I have no memory at all,’ Orville was frank to say, ‘but he never forgets anything.’ . . . . Orville was the more gentle of the two. Though talkative and entertaining at home, often a tease, outside the house he was painfully shy, something inherited from their deceased mother, and refused to take any public role, leaving all that to Wilbur. But he was also the more cheerful, the more optimistic and naturally entrepreneurial, and his remarkable mechanical ingenuity figured importantly in all their projects.”

The Wright family house in Dayton, Ohio, which the brothers shared with their father and younger sister, Katharine, was filled with books. The whole family read constantly. Wilbur became even more devoted to reading as a young man, following a bizarre episode that appears to have significantly altered the course of his life. A gifted athlete, he was playing hockey one day when he was struck in the face with a stick, losing most of his upper front teeth; a passage in his father’s diary from years later refers to the “man who threw the bat that struck Wilbur,” the man being Oliver Crook Haugh, who was executed in 1906 for killing his parents and brother and who, according to McCullough, “was believed to have killed as many as a dozen others besides.” Following the bat incident, Wilbur suffered from physical problems and a bout of depression, and all talk of his attending Yale University—or any college—ended forever. That tough period coincided with his mother’s decline in health, and the housebound Wilbur became his mother’s caretaker.

The Wright family house in Dayton, Ohio, which the brothers shared with their father and younger sister, Katharine, was filled with books. The whole family read constantly. Wilbur became even more devoted to reading as a young man, following a bizarre episode that appears to have significantly altered the course of his life.

A few years later his reading took a new direction after he learned about Otto Lilienthal, a German gliding enthusiast who had recently died in an accident. Wilbur read aloud about Lilienthal to Orville, who was recovering from typhoid. The more Wilbur and Orville learned about Lilienthal, the more an old interest of theirs—flight—was revived. The brothers began putting their minds to solving a mystery as old as humanity.

3.

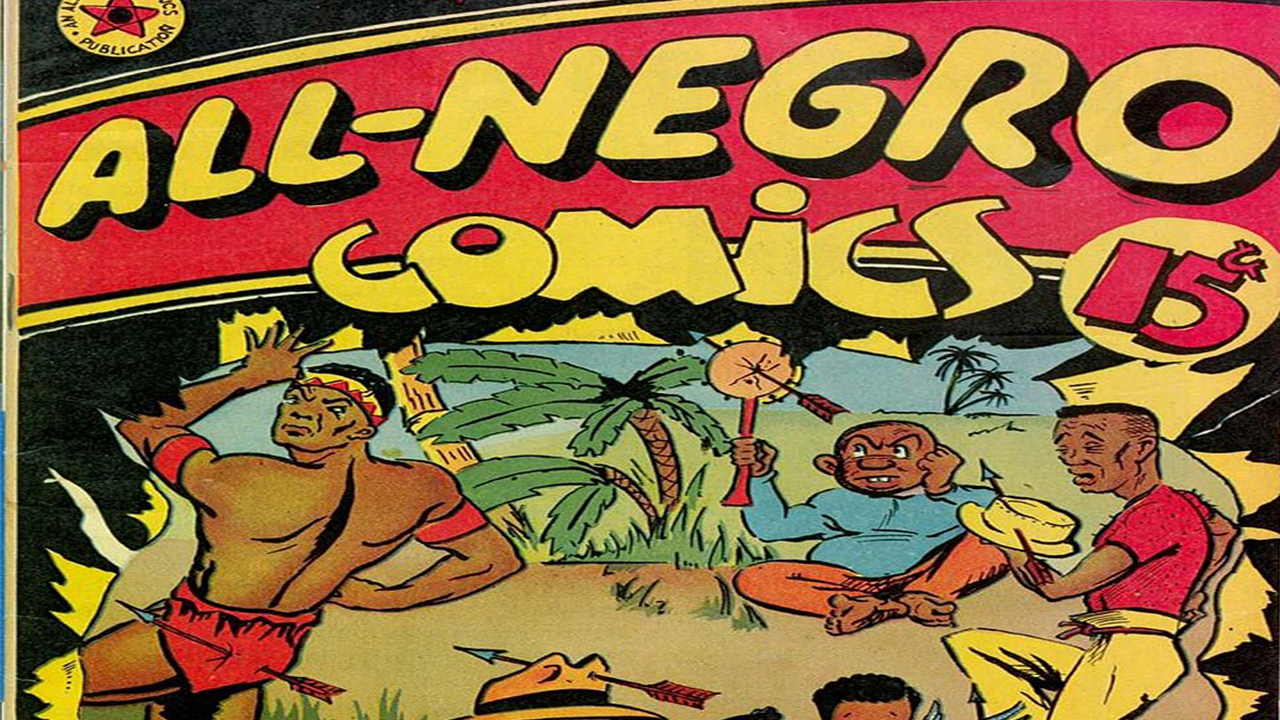

Some mysteries are technical in nature; others are about who did what. Still others have more to do with one’s philosophy. For example: millions of people are taken forcibly from their homes in Africa and sold into bondage in what eventually becomes known as the United States of America. This fact significantly alters the course of their descendants’ lives. Generations of these enslaved Africans live and die before slavery ends in their adoptive home, which becomes the only home they know. For nearly a century after the end of slavery, segregation of these people from other Americans remains the law of the land, and the descendants of the enslaved Africans are subjected to all manner of hardship because of their lineage. In part for these reasons, a culture and set of traditions grows among the descendants of the enslaved. Finally there comes an end to legal segregation; discrimination against the descendants, at least officially, also comes to an end. While many of these descendants continue to suffer from the ramifications of what was done to their ancestors—including poverty from lack of accumulated wealth, a fatally biased law-enforcement system, and other forms of ongoing discrimination—many others are, at least comparatively speaking, able to thrive.

Part of the mystery, for those concerned with it, is how to maintain one’s equilibrium: How does one balance knowledge of wrongs committed in the past with the necessity of living in the present?

The mystery, then, for those descendants who are not focused on mere survival and have the luxury to think about such things, is: what is the proper attitude to take toward their country and fellow countrymen? Is it, in fact, the descendants’ country? Or are they really Africans, by virtue of (1) descent and (2) the fact that the United States of America does not always afford them the comfort, emotional and otherwise, that one associates with one’s home? How should they feel about Americans who are not of African descent, who—as they are quick to say—never made anyone sit at the back of the bus, but who nevertheless benefitted in all kinds of ways from a society built on the backs of the enslaved?

Part of the mystery, for those concerned with it, is how to maintain one’s equilibrium: How does one balance knowledge of wrongs committed in the past with the necessity of living in the present? How does one live among Americans of all stripes without simply being angry all of the time?

What separates philosophical mysteries from other kinds is that, when they are solved at all, they are solved in different ways, resulting in the discoveries of different “truths,” depending on who is doing the solving. For example: one writer, a descendant of enslaved Africans, decided—inspired largely by the writings of descendants before him—that his tie to the United States of America was determined by his pride in the achievements of other descendants in this adoptive country. For him, these achievements are symbolized by jazz, one of whose most significant figures was nicknamed Bird.

4.

“Equilibrium was the all-important factor, [Wilbur and Orville] understood. The difficulty was not to get into the air but to stay there, and they concluded that Lilienthal’s fatal problem had been an insufficient means of control—‘his inability to properly balance his machine in the air,’ as Orville wrote. Swinging one’s legs or shifting the weight of one’s body about in midair were hardly enough.

Wilbur’s observations of birds in flight had convinced him that birds used more ‘positive and energetic methods of regaining equilibrium’ than that of a pilot trying to shift the center of gravity with his own body. It had occurred to him that a bird adjusted the tips of its wings so as to present the tip of one wing at a raised angle, the other at a lowered angle. Thus its balance was controlled . . . ”

—David McCullough, The Wright Brothers

Balance was maintained, then, paradoxically, by coming at things from an odd angle.

5.

Among African Americans who have achieved fame, many have done so by coming at things from odd angles. Perhaps a notable Black American is, by definition, one concerned with an odd angle on things. In any case, examples abound in jazz. Louis Armstrong essentially invented the jazz solo, blowing trumpet lines that stood apart from what the rest of the band was up to. He altered the course of singing, too, that gravelly voice of his introducing a certain knowingness into the proceedings.

Fashioning music out of those higher intervals was akin to dancing on air—or, you might say, flying.

Then there was the alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, also known as Bird. Bird’s innovation began with a mystery: how to make audible the sounds in his head. Before Bird, jazz had been situated on a traditional set of chord changes. His innovation was to play melodies, in his signature thin, metallic tone, based on the higher intervals between notes in chords, with corresponding chord changes. Fashioning music out of those higher intervals was akin to dancing on air—or, you might say, flying.

6.

Relationships are mysteries—why they work, why they do not, what is at the heart of them. One’s relationship to one’s country can constitute a mystery. So, of course, can one-on-one relationships, those between friends, or parents and children, or siblings, or romantic partners. McCullough’s biography of Wilbur and Orville Wright has very little to say about their relationships with anyone outside their family; what it does say, though, is fascinating, perhaps chiefly because it raises more questions than it answers, creating a mystery one is almost reluctant to have solved. Neither brother ever married, and there is nothing in the biography to suggest that either Wilbur or Orville ever so much as kissed anyone. That is what makes the presence in their lives of their younger sister, Katharine, so darkly fascinating. Katharine Wright was, like Wilbur and Orville, a down-to-earth—so to speak—person who fully supported her brothers’ efforts. In 1908, Orville survived a crash while flying with one passenger (the passenger represented the first fatality in the history of powered flight); Orville suffered grave injury and had a long recovery, during which Katharine never left his side.

Katharine lived with her brothers in Dayton. That changed the year that Katharine—a high school Latin teacher who had graduated from Oberlin College and served as an active alumna—announced in 1926, at age fifty-two, that she was marrying an Oberlin classmate. At this news, in McCullough’s words, Orville was “furious and inconsolable.” (Wilbur had been dead for fourteen years by that point.) Feeling betrayed, Orville did not attend the wedding, and when, three years later, he learned that his sister was dying of pneumonia, it was only at the last moment that he decided to see her.

7.

I graduated from Oberlin College in 1985. That year my romance with a fellow Oberlin student, who was in the class behind me, became long-distance. During one visit to see her that fall, I learned about a betrayal. That news did not bring about our breakup, which occurred months later, though it could be called a harbinger.

One thing that I remember about that trip, and that struck me at the time as a little too metaphorical, was the return journey to my home in Washington, D.C. I traveled by airplane, one of the smaller planes I had ever been on. The flight was memorable for turbulence that was worse than any I had experienced before or have since. A flight attendant, standing near me, fell down. When we reached the ground, a woman across the aisle told me she had been scared. I told her she was not alone.

8.

Relationships can be vexing. They are also, of course, necessary to human life, and they can be quite productive. The fictional Hardy Boys combined their talents to solve mysteries; the real-life Wright brothers combined theirs to give the world the first sustained powered flight, in the process altering the course of human history.

Even jazz was the result of a partnership, or partnerships, not only between people but between peoples. Important elements of jazz include African-derived rhythms; they also include European-derived melodies, which African Americans, coming in from an odd angle, bent to their own purposes. And so, for some of us, the key to solving the mystery of our relation to our country lies in a collaboration of sorts between our ancestors and our oppressors. Some would rather die than embrace this idea; others of us find it endlessly fascinating. We will file this under P for “philosophical mysteries.”

The fictional Hardy Boys combined their talents to solve mysteries; the real-life Wright brothers combined theirs to give the world the first sustained powered flight, in the process altering the course of human history.

Collaborations abound, meanwhile. I had been a fan of the Hardy Boys series for at least a few years before I discovered that there was no such person as Franklin W. Dixon—that the mysteries were the collective work of ghostwriters.

9.

The Hardy Boys series did not make me into a particular fan of mystery novels. I have loved a few, though, including books by Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Chester Himes, and Walter Mosley. Some young adult books bear re-reading as an adult; the novels in the Hardy Boys series are not such works, since, if memory serves, they are not concerned with any mysteries behind the mysteries. The best detective novels, by contrast, have as their ultimate, unspoken mystery how one should live.

If we think of it that way, perhaps every good novel is a mystery. I think of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, which makes mention of legends of Africans who could fly . . .

10.

When I was a boy, Alex Haley’s years-long dive into the mystery of his own African ancestry resulted in the publication of his book Roots (1976). That runaway best-seller was followed by a television miniseries of the same name, which set records for viewership. It later surfaced that the African Kunta Kinte was likely not, as Haley had claimed, the same man as the enslaved figure Toby, from whom Haley was descended. For the purposes of Roots, as with the case of Franklin W. Dixon, different people had become one. (With that discovery, Roots went from the nonfiction to the fiction column on best-seller lists.) It hardly mattered: Roots (book and TV show) sent untold numbers of Black Americans in search of their African roots.

That search became much easier with the advent of DNA-based heritage-tracing services, of which many people have made use. One of those people is my sister, who discovered that our ancestors are from southern Africa. She has decided that we come from Botswana, mainly because that is the home country of Mma Precious Ramotswe, the main character of the novels in Alexander McCall Smith’s series No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency, which my sister loves.

11.

As I write this essay, I am listening to Bird’s records. I love the inventiveness, the breakneck pace, and the flights of fancy of his melodies. I admire his daring and ingenuity, just as I do the Wright brothers’ daring and ingenuity: over a century after they occurred, it is thrilling to read accounts of their first successful powered flights.

Later, I will read a book—a longtime habit whose seeds were planted by my cousin’s gift of Hunting for Hidden Gold—while listening to jazz and sipping whiskey. I often read without drinking, though, unless I am with other people, I almost never drink without reading. The combination of good music, a good book, and good bourbon sends my imagination, and my optimism, into flight. Such is often the process: mysteries, so essential to human progress, are hatched, as are their solutions, in the human mind.