The Show of Shows

Flip chronicles America's most influential, but least remembered, black comedian

By Gerald Early

October 1, 2014

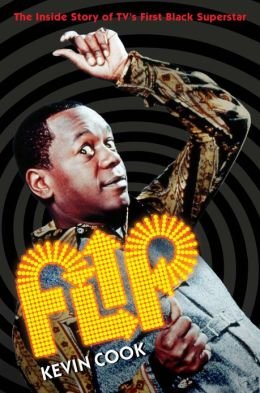

Flip: The Inside Story of TV’s First Black Superstar

Comedian Flip Wilson did something neither singer/dancer Sammy Davis, Jr. nor singer Nat King Cole could do: become the first black entertainer to successfully host a TV variety show. Cole’s show aired Monday nights on NBC during the fall 1956-spring 1957 television season (thirty-four 15-minute programs) and on Tuesday nights from July-September 1957 (nine 30-minute shows). Cole was never able to attract a national sponsor, all of whom were afraid of offending white Southerners and bigoted Northern whites by sponsoring a black show. The best NBC could do was attract a few local businesses like Rheingold Beer and angels like Frank Sinatra. Cole was one of the most well-known and well-liked black entertainers of the era, a stylish vocalist and fine jazz and cocktail pianist. His recordings received a great deal of radio-play and sold well. If a variety show with a black host was to succeed, Cole was a good bet to do it as he had a huge white following as well as loyal, ardent black fans. Earlier efforts by singer/pianist Hazel Scott (1950) and singer Billy Daniels (1952) died almost as soon as they were born. Only trumpeter Louis Armstrong would have been a better bet than Cole. But either Armstrong wasn’t offered or, more likely, he knew better.

“For 13 months, I was the Jackie Robinson of television,” Cole said in the February 1958 Ebony magazine interview. And so he was, but with a lot less success than Robinson. Few blacks were featured on television at the time; Amos ‘N’ Andy, the televised version of the wildly popular, Depression-era radio comedy show about two black buddies and their various misadventures in Chicago had been protested off the air by the NAACP, on the grounds of being a degrading stereotype of blacks, after running from 1951 to 1953. Blacks appeared so infrequently on television then that black households made a big deal of any guest black appearance, no matter how minor. Cole’s show was never able to attract a large enough audience to entice a sponsor to take a risk, or, more precisely put, a large enough audience for a black host, which almost certainly had to be larger than a white host would need to get sponsors. Blacks watched in great numbers (although their ownership of televisions at the time was lower than whites) but whites, by and large, were not nearly so inclined. This was still the age of Jim Crow in the United States, despite the 1954 Brown decision that desegregated public schools, despite Jackie Robinson’s integration of major league baseball in 1947, and despite the integration of the American military by presidential executive order in 1948. It was the age of the horrific murder of Emmett Till, the nonviolent defiance of the Montgomery bus boycott, and the violent, determined resistance of Southern whites to integration with the rise of white citizens’ councils, the Ku Klux Klan, and the steady flight of whites from cities to the suburbs. It is not surprising that Cole’s show could not sustain itself but that it lasted as long as it did.

Sammy Davis, Jr.’s attempt in 1966 seemed more likely to guarantee a success. If anything, Davis, who was then at the height of his fame, was even more popular than Cole had been. (Cole died of lung cancer in 1965. Both he and Davis were heavy smokers and Davis would die of throat cancer in 1990.) By this time, although the United States was in the middle of the fires of the Civil Rights movement—with the Selma March, the March on Washington, and the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts on the one hand that broke the back of legalized segregation, but with the rise of Black Power, the 1965 Watts riot and greater urban unrest, and the rise of “law and order” conservatism on the other—there was far more interest in having blacks appear on television. Rock ‘n’ roll had succeeded in breaking down some of the racial barriers in teenage dance music; Motown’s girl act, The Supremes, had become the most successful crossover act in the history of American music; Sidney Poitier had become America’s most successful and honored black dramatic actor. Change had accelerated.

He filled hundreds of legal pads over the course of his life making wry observations and generating random analysis about “the funny.” His first stand-up routine which he performed while in the Air Force was the sex life of coconut crabs. It went over very well.

Davis was a popular recording artist and a highly successful nightclub act, particularly as part of Frank Sinatra’s Rat Pack that included Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop. Davis managed to come back from losing an eye in an automobile accident in 1954; he converted to Judaism, married a white woman (Swedish actress May Britt), and seemed as assimilated, as integrated as a black performer could possibly be. He would surely bring a huge white audience with him to the hour-long show, which had national sponsors. At the time the show aired, Davis had published a best-selling autobiography, Yes I Can, starred in a major drama film about a jazz trumpeter, A Man Called Adam, and starred in the Broadway musical version of Clifford Odet’s Golden Boy, which opened in 1964 and ran for more than 500 performances. As Davis himself was later to admit, he was, at the time of television show’s debut, overcommitted and under contractual obligations that worked against his show. The show was doomed to failure as Davis only hosted one time in the first four weeks, using Johnny Carson, Sean Connery, and Jerry Lewis as guest hosts. Any hope of Davis establishing a rapport with an audience, building an audience, was gone. Once Davis finally began to appear regularly, the quality of the show improved but it was too late. Davis was a magnetic performer and a gregarious, if occasionally unctuous or obsequious, host. He did not last as long as Cole; The Sammy Davis, Jr. Show ran from January to April 1966, a total of fifteen broadcasts.

“Money Won’t Change You …”

So why did a modestly-talented comic, Flip Wilson, succeed in 1970 where two men who were more gifted artistically did not? Kevin Cook’s biography, Flip, offers some answers. For instance, when NBC was developing a show for him, “Audience research showed Flip Wilson topping the charts in a factor called likability. As Richard Pryor told Flip, ‘You’re the only performer who goes onstage and the audience wants you to like them.’” There was something both guileless and wily about Wilson, a combination that made him appealing in such troubling times. After all, by 1970, the United States was torn apart by protests over the Vietnam War; whites were fatigued and increasingly impatient with the demand for black rights and seemingly endless cycles of urban violence; the assassinations of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy, and the attempted assassination of segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace, made many feel the country was resorting to bloodshed to resolve its political differences. Yet with the War on Poverty and the creation of Medicare, there was a sense of hope, even of social mission in American national politics.

Blacks, by this time, were being courted as a taste public and as a consumer group. In 1965, red-hot comic Bill Cosby co-starred with Robert Culp in the action television series, I Spy, which ran for three seasons. In 1966, former football star Jim Brown had a significant supporting role in The Dirty Dozen and by 1969 was starring with the era’s sex siren, Raquel Welch, in One Hundred Rifles. In 1968, Diahann Carroll starred in Julia, the first primetime television program to feature a black woman in the lead who was not a domestic. (Carroll played a widowed nurse.) By 1970, there were the first stirrings of Blaxploitation cinema with the premiere of Cotton Comes to Harlem, a film based on a novel by African American writer Chester Himes. During Flip Wilson’s time on the air, Blaxploitation films would have their full flowering with the emergence of Sweet, Sweetback’s Badass Song (1971), Black Caesar (1973), Cleopatra Jones (1973), Foxy Brown (1974), and other such fare.

From this cultural and political cauldron, Wilson was especially winsome; he seemed like the sort of black person, wide grin, pleasant personality, that any white person would want for a friend; yet the twinkle in his eye made one feel as if he knew something that you didn’t, but that you should. He seemed personable but shrewd. As Cook writes:

“The January 31, 1972, cover of Time magazine showed Flip under a halo of stage lights and a banner that dubbed him ‘TV’s First Black Superstar.’ Roland Flamini’s cover story hailed a comedy idol whose show was ‘regular Thursday night fare for an estimated 40 million Americans.’ Flip had five million more viewers than any president has gotten votes. …Flamini thought he knew Flip’s secret: ‘He has the talent to make blacks laugh without anger and whites laugh without guilt.’”

Wilson was the right person at the right moment. Distinct from Bill Cosby in that Wilson’s persona was not the all-American dad or the all-American big brother telling jokes that seemed raceless, Wilson neutralized his race by being the hip, slightly funky black comic, aware of his race, slyly ethnic, to be sure, with his characters Reverend Leroy, the black preacher, and Geraldine, the sassy black woman, but who made blackness acceptable, even middle-American, by making himself, to use comic actress Lily Tomplin’s phrase, “loveable and cute.”

Cook’s biography tells the story of Clerow Wilson, born in Jersey City, New Jersey in 1933. The man he believed to be his father made fun of his dark skin color (“You’re as black as burnt toast.”) His mother ran off with another man and took no interest in him. (He grew up hating his mother and being generally distrustful of women.) He did not distinguish himself in school, for the most part, seeming very ordinary, except for two aspects of his personality. He loved to talk and he liked making people laugh. As he was not a physically imposing person, making people laugh was a way to disarm people who might be disposed to harm him; so it was for him, as for many other comics, a method of survival. From the time he was taken to see a stage show as a child, he wanted to be an entertainer. Nothing else in his life seemed to matter and he had nothing else going for him in his life.

It was during his stint in the Air Force (he enlisted in 1950) that Wilson discovered, first, that he had remarkable clerical skills; second, that he could be a successful stand-up comic; and, third, that he loved dope, a love he would cultivate his entire adult life with marijuana and cocaine in large quantities. Wilson was serious about being a comic; he read books on the art of being funny. He studied other comedians, taking copious notes, not stealing their material but noting their technique: what worked for them and why. “I analyzed [other comics] to find out what made them great,” he said later, “and fund that most of them had one special characteristic. With Bob Hope, it was his timing. With Jerry Lewis, his dynamics—the way he moved. George Burns was effortless. Rochester and Butterfly McQueen had unique voices.” He filled hundreds of legal pads over the course of his life making wry observations and generating random analysis about “the funny.” His first stand-up routine which he performed while in the Air Force was the sex life of coconut crabs. It went over very well. Wilson knew he had something. He honed his craft as an itinerant nightclub comic, traversing the country (exhibiting a wanderlust he would never lose), making friends with other comics, developing his technique, his stories, his characters. He had an incredible range of knowledge about what made people laugh. It was not so much what a comic said as the way he said it that could make the difference between laughter and indifference. He distilled Max Eastman’s Enjoyment of Laughter (1936) down to one maxim: Be Interesting, Be Effortless, Be Sudden. One night, doing his stand-up before his fellow servicemen, he spoofed Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. During the applause, someone called out “He flippeth his lid.” Flip Wilson was born.

After years of being in the entertainment wilderness or the entertainment woodshed, Wilson got three breaks in fairly quick succession: first, he was a hit at the Apollo Theater, the Harlem Mecca of black popular culture, which led to his being regularly featured there; second, he got a gig at the Village Gate, a hip New York nightclub that catered to the Café Society-type crowd, where his act was more edgy and “dirty”; third, in 1964, comic and long-time friend Redd Foxx, while doing a guest bit on The Tonight Show was asked who was the funniest comedian on the scene at that moment. He answered, “Flip Wilson.” Wilson’s first appearance on The Tonight Show was a success (Johnny Carson loved him) and his career was made.

The Flip Wilson Show ran from 1970 to 1974. During those years, Wilson was one of the highest paid black entertainers in the world. The show’s ratings were astronomical in its first year; very good in its second year; good in its third year, and declining rapidly by the fourth and final year, when Wilson announced he was quitting rather than have NBC cancel the show for insufficient ratings. The excitement the show generated was partly what Wilson called his “fruit salad” mix of guests, white and black, from the controversial like Muhammad Ali to the up-and-coming like Michael Jackson to the professional stalwart like Tim Conway, who was something of a semi-regular, and Australian singer Helen Reddy. The writers included not only Wilson himself but older pros that had written for Milton Berle and Jack Benny as well as drugged-out young guns like George Carlin and Richard Pryor, who would become major stars, in part, because Wilson used them. Despite contributions from others, Wilson was the auteur of his show. He controlled every aspect of it. Choreographed it right down to the flubs and bloopers which were planned and rehearsed. Even having the performers laugh out loud as they were performing the skits, seemingly amused by their own lines, as was common on the Carol Burnett Show, the Dean Martin Show, and the Red Skelton Show, was rehearsed and calculated, not spontaneous at all. He worked 18-hour days for four years, fueling himself with dope to keep going. His children rolled his marijuana cigarettes for him.

He achieved his dream. He was rich, famous, had his own hit television show, was one of the most admired men in America. He had become the perfection of himself. All that was left was life and the undoing of everything he thought had meaning.

“But Time Will Take You Out”

After The Flip Wilson Show, Wilson never enjoyed any comparable career success. It was unclear whether he wanted any such success again. It was as if he had realized his dream with the show and there was really nothing left for him to do. Unlike Cosby, Carlin, and Pryor, he never became an actor. He starred in a sitcom entitled Charlie and Company, with singer Gladys Knight in 1985, an answer to Bill Cosby’s highly successful sitcom that was ruling the rating roost at that time. Cosby’s show lasted eight years, Wilson’s only lasted one. His heart was never in it because he never wanted to be an actor. He had a love/hate relationship with his children, who found him generous, overbearing, self-centered, guilt-ridden, and neglectful, as successful show business parents can often be. He took up one fad after another. One of them, motorcycling, led to his son David becoming a quadriplegic as a result of freak accident. Wilson continued during these years to use large quantities of dope while deluding himself that he was not an addict, while memorizing Kahlil Gibran, and taking road trips to nowhere in particular. He gave all the appearances of a man who wanted to escape himself but could not figure how to do so. His success, for which he, like all of us, hoped would be a key to liberating his true self, only made him more restless, bored by his old desires, and optimistic that his newest craving may be true at last. He had too much time on his hands. As he faded away from the limelight, he was forgotten by his audience, was unknown to the audiences who came after. He became a footnote in American racial and cultural history. One of his last public interviews was on the Howard Stern radio program one year before he died. Wilson talked about a medical procedure where he had a pump implanted in his penis. “So many women, so little time,” he said. He then dropped his pants to demonstrate the device. For a man who boasted that one of his most important accomplishments was having sex with six women at the same time, the fear of impotence must have been great. The fear that having sex with six women at the same time was meaningless, even absurd, was even greater. Living one’s fantasies may be a greater source of torment than constantly desiring to live them with no real chance of doing so. He died on November 25, 1998, of cancer. The only real show of shows is life itself and that gets canceled too, whether or not the ratings are high.

“Flip set ratings records and helped bring dozens of worthy performers, many of them black, into the American mainstream at a time when other variety show hosts played it safe,” writes Cook. “You could say that Flip was the first and last of his kind.” He brought a new, fresh, respectable black humor to the mainstream which became dated almost as quickly as it bloomed. “[He] was a man of his time who changed his time,” writes Cook. Some years from now, there will be a deeper, richer book on Flip Wilson, but Cook’s effort is informative, insightful, sprinkled with good examples of Wilson’s jokes throughout. It will do for now.