Chuck Berry’s Blues

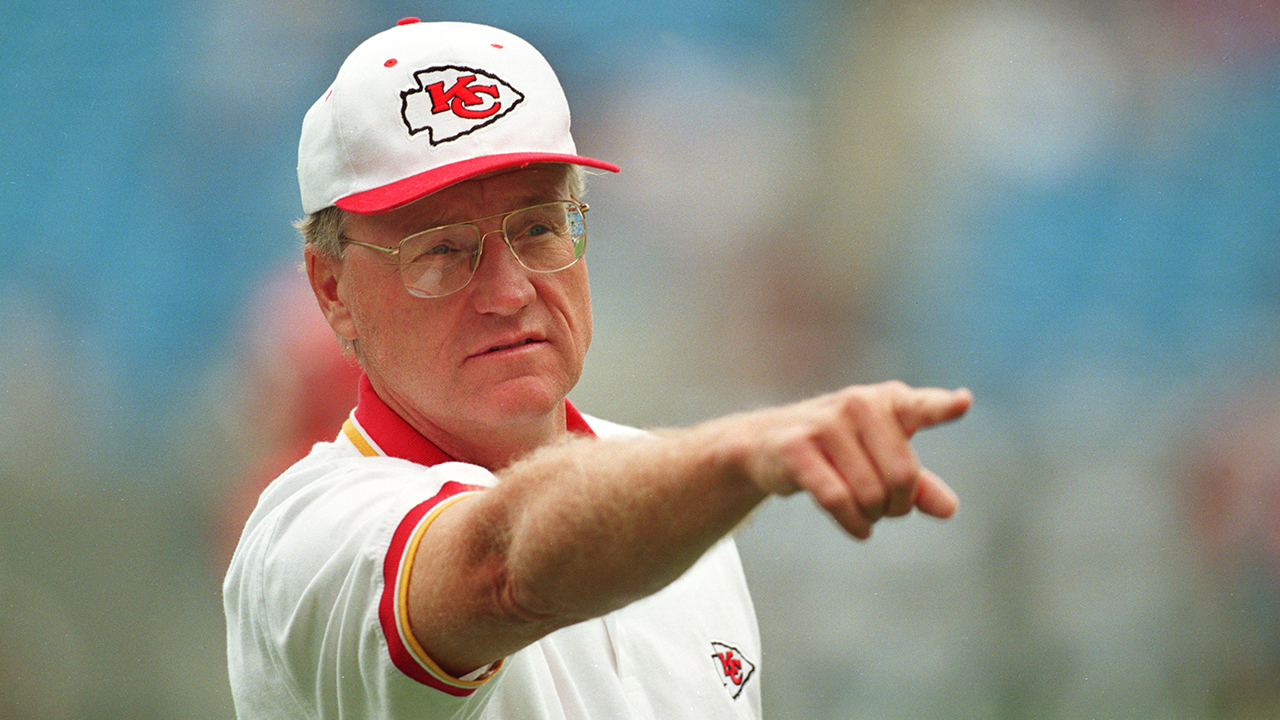

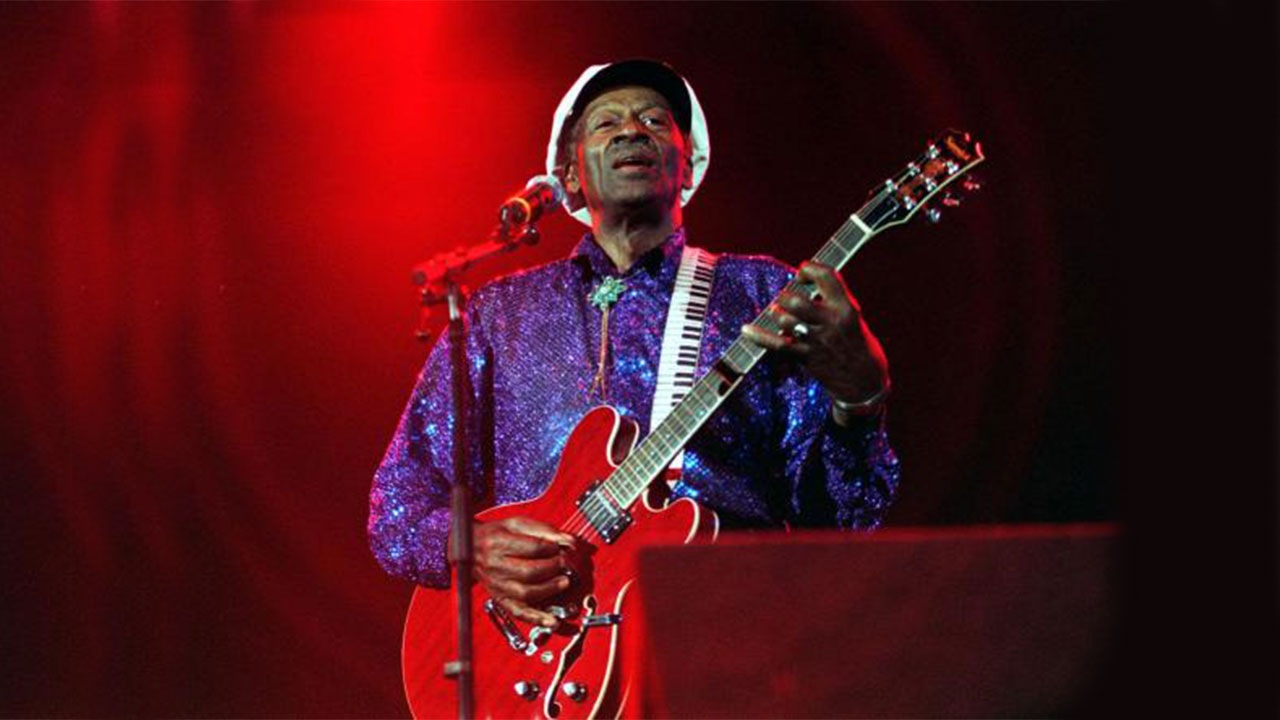

Hail! Hail! Rock 'n' roll's founding figure, 1926-2017.

March 20, 2017

“Talking to Chuck Berry about his music is a little like meeting God and finding out He doesn’t remember making the Earth or care what people did there.”

—Bill Flanagan, Written in My Soul

There are at least two great mysteries about Chuck Berry. The first is why the father of rock ‘n’ roll, the consummate striver who worked tirelessly for his shot at stardom in the ’50s, the master craftsman whose songs exhibited so much lyrical precision, became so cavalier and dismissive about his work once he achieved that popularity. To look at Berry’s career from any angle, be it musical, personal, financial or psychological, is to see a man increasingly embittered and alienated from the outside world, even as he keeps flashing his signature smile. That dichotomy leads to the second mystery, which is how someone so deeply scarred as Berry could continue, at least for a period in the ’60s, to create music infused with so much joy, feeling, whimsy, and bristling intelligence.

Elvis Presley will forever remain rock ‘n’ roll’s totemic, galvanizing figure. But without Berry to further refine and define the musical form, it may well have withered on the vine. His seminal double-string guitar style provided an unshakable sonic foundation upon which generations of others would build. Through his astonishing lyrical gifts he had a similarly powerful impact, not merely expanding the vocabulary of popular music but codifying the idea of rock ‘n’ roll.

Berry was 29 years old when he completed his first composition, and for the next decade his songwriting distilled modern American urban youth culture in all its seductive trappings. “They’re really rockin’ in Boston, and Pittsburgh, P-A/ Deep in the heart of Texas, and round the ‘Frisco Bay,” he sang. This was not merely a call for something as inconsequential as a fad or a new musical style, but something more profound and lasting, a social revolution that would resonate across the country and the decades. What Brown v. Board of Education did for American schools, rock ‘n’ roll would do for American culture: It set the country inexorably on a path where it would have to reconcile itself to its own egalitarian ideals. Roll over Supreme Court, and tell George Wallace the news …

After watching the three discs of behind-the-scenes extras, it seems clear that in the event the filmmakers were not being unfair to Berry; if anything, they soft-pedaled the prickly nature of his persona.

After too long of a wait, the excellent 1987 documentary Chuck Berry Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll has been released on DVD, in a lavish four-disc boxed set that includes nearly eight hours of additional footage, ranging from the obligatory—and in this case, highly informative—documentary about the making of the film to several hours of largely unedited interview footage with many of the founding fathers of rock ‘n’ roll (including an inebriated, edgy and only occasionally coherent Jerry Lee Lewis), who were interviewed for the picture. Next to Berry’s music itself, director Taylor Hackford’s intimate, engrossing, flawed film may well remain the most lasting testament we have to Berry’s revelatory artistry. As an insight into the true nature of the enigmatic, confounding man himself, the package raises as many questions as it answers.

highly informative—documentary about the making of the film to several hours of largely unedited interview footage with many of the founding fathers of rock ‘n’ roll (including an inebriated, edgy and only occasionally coherent Jerry Lee Lewis), who were interviewed for the picture. Next to Berry’s music itself, director Taylor Hackford’s intimate, engrossing, flawed film may well remain the most lasting testament we have to Berry’s revelatory artistry. As an insight into the true nature of the enigmatic, confounding man himself, the package raises as many questions as it answers.

Much of the movie was shot during a week in the fall of 1986, culminating with two concerts held at the Fox Theater in St. Louis. In the days prior to the show, Hackford filmed Berry in and around the city, spending long hours at the singer’s Wentzville home, where Berry rehearsed with an all-star band led by his greatest disciple, the Rolling Stones’ indomitable guitarist Keith Richards. It was Berry’s rote, pedestrian live touring shows—sloppy, stingy hourlong affairs, always with a hired local band of complete strangers—that convinced Richards he owed it to his inspiration to “set Chuck up with a proper band.”

This much he clearly did. The concert material shot at the Fox that made it into the film is almost uniformly strong, with Robert Cray sweetly leading the band through “Brown-Eyed Handsome Man,” and an energetic Linda Ronstadt pairing with Berry on “Livin’ in the U.S.A.” Time stands still during the lone clinker, Berry’s duet on “Johnny B. Goode” with a shrill, green Julian Lennon (looking disconcertingly like the singer k.d. lang). But even this is redeemed by the show-stopper, in which Berry and Etta James give a joyous rendition of “Rock ‘n’ Roll Music,” with James’ powerful voice and formidable presence raising stakes which the beaming Berry gladly calls.

More interesting than the songs themselves is the footage documenting the rehearsals to prepare for the performance (perhaps the only conscientious rehearsing with a band that Berry had done in decades), during which we see the inevitable, titanic clash of wills between Berry and Richards—what the director Hackford describes as “the alpha male thing between Chuck and Keith.” The pair is shown arguing loudly, first over the way Berry sets his amp for recording the rehearsal, then over the style in which Richards plays Berry’s signature opening guitar riff on “Carol.” We begin to get a sense just how obstinate the star has become, and how hard he can make it on those who care about him.

The proud gypsy Richards proves equal to the task. He moves through the film like a prodigal son returning home to celebrate the life of a father who might have grown too bitter and crotchety to abide a proper celebration. There are moments in the rehearsal standoffs when Berry is so maddeningly obdurate that if Richards had literally bitten his tongue, he surely would have drawn blood. Instead, he takes another swig of beer and glares meaningfully at one of his bandmates, steadfastly fulfilling his mission, tolerating Berry’s willful behavior for the greater good.

The interview with Richards, which we see glimpses of throughout the film, occurred in the hours following the second and final concert at the Fox, when he had been awake for more than 36 hours. Working on an ever-present cigarette, hair disheveled, the famously careworn face looking all the more lined, Richards sits back regally in a chair, a bottle of bourbon in a nearby sink, recounting the experience. And in these moments, he becomes the conscience of the film, the man willing to speak the hard truths that no one else at the time had the nerve to utter. Crucially, Richards—a man as famed as Berry for living life on his own terms—saved those truths until after the concerts, for he must have realized that if he had said them to Berry’s face during the week of rehearsal, the picture might never have gotten made.

It nearly did not get made anyway. In the movie, Berry is by turns vibrant and wistful, modest about his talents and yet justifiably proud of all he has accomplished. But he also comes across as a domineering, disingenuous, licentious, money-hungry, philandering bully, who could get away with this and more because of a combination of genuine charm, a commanding presence, and a darkly Machiavellian streak.

After watching the three discs of behind-the-scenes extras, it seems clear that in the event the filmmakers were not being unfair to Berry; if anything, they soft-pedaled the prickly nature of his persona. This is certainly the only The Making Of… documentary I have ever seen in which the film’s producer (Stephanie Bennett) recalls throwing a bagful of cash at the star and telling him what she really thought of him, or mentions rather wearily that if he had not made a pass at her, she would have felt insulted, “because he made a pass at every other woman on the set.”

Through his astonishing lyrical gifts he had a similarly powerful impact, not merely expanding the vocabulary of popular music but codifying the idea of rock ‘n’ roll.

Those who have followed Berry’s career closely will not be surprised at any of this. We hear about him showing up for a pre-production meeting at a chic restaurant in the Hollywood Hills with a sack from McDonald’s containing a hamburger, soda and an apple pie. His apoplectic host stammered that he would certainly be glad to buy Berry dinner. “I know what I like to eat,” Berry responded. “Now let’s get down to business.” His penchant for keeping outsiders off balance is well known, but there is something more at work here, an undeniable coldness to the man. The documentary about the making of Hail! Hail! relates that Berry led a contingent including two women to a visit to the grounds of the Algoa Correctional Center (where he served time) in Missouri, then nearly prompted a riot by walking away and leaving the two females (one of whom was the producer Bennett) unaccompanied in a prison yard full of hundreds of inmates. The various descriptions of the effort to get those women to safety—through the jeering, groping mass of inmates—is harrowing, as is the account of how indifferent Berry was about the whole matter afterward.

We also learn that Berry held the entire production hostage, calling upon the first day of shooting, demanding $10,000 more in cash before he would deign to show up. This would be a recurring theme during the week of shooting. Despite all of this, Hackford remains warmly admiring of Berry and his artistry. This echoes a sentiment that Richards delivers near the end of the film: “He’s caused me more headaches than Mick Jagger, but I can’t dislike the man.”

• • •

“The music was so dead at that time that all you had to do was back the hearse up and bring the coffin. Rock and roll to me was like an explosion … like a great big explosion.”

—Little Richard

The third and fourth discs of the DVD package are dominated by interview segments with many of the crucial personalities who figured prominently in the berth of rock ‘n’ roll. The seminal figures seem as in the dark as anyone else about the true genesis of the form. Roy Orbison comes closest, citing a New Year’s Eve night he and his combo spent at a West Texas honky-tonk, where they tried to comply with a request for Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” The strong backbeat kicked in and, in Orbison’s words, “that was when the rhythm caught up with the blues … it was terrific.”

That Berry would play such a pivotal role in the revolution is something of a miracle. His first stint in prison, for stealing a car, came in 1944, before the 18-year-old had graduated high school. Consider the prospects of a young man who, in the midst of World War II, is convicted of a crime. Berry would have been serving time on both VE and VJ day, and its hard to think of a greater sense of disconnection than being a black American behind bars on the days when the United States successfully saves the free world.

But America, as ever a land of reinvention, offered Berry a second chance, first through physical labor, then cosmetology school and later music. In turn Berry, in so many ways the archetypal self-made man, seized upon the opportunities at hand. The hard work he did during his first time in prison (earning his high school equivalency degree and reading poetry) eventually paid off, as he took his guitar to the Cosmopolitan Club in East St. Louis, where he joined and eventually took over the trio that had been fronted by Johnnie Johnson, a top-level boogie-woogie piano player who would become Berry’s longtime friend, foil and, in many eyes, silent collaborator.

Keith Richards posits in the film that it was not Berry who wrote the music to his hits at all, but instead Johnson. There is enough circumstantial evidence to support this theory. Berry’s music is written in unusual keys for a guitar player, and he hadn’t written any musical compositions of his own prior to his audition with Leonard Chess (he had written plenty of poems and verses, and he had adapted some of this doggerel to other people’s songs, including a reworking of “South of the Border” into a song with a risqué punchline, “That Louse of a Boarder”). In the week after his first meeting with Chess, Berry returned to St. Louis, spent time making some demos with Johnson, and returned to Chess with four new songs. “He ain’t copying Chuck’s riff on piano,” argues Richards. “Chuck adapted them to guitar, and put those great lyrics behind them. But without somebody to give him them riffs—voila!— there’s no song. Just a lot of words on paper.” The film then cuts to Johnson, looking utterly guileless, taking pains to explain, “No, I didn’t write the music with him, I’d just sometimes be in the room with him while he was writing.” Johnson then proceeds to describe a process that sounds exactly like the collaborative one used by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones and other groups in which multiple composers share songwriting credit.

When Johnson finally sued Berry for royalties and songwriting credit in 2000, a court dismissed the case on the grounds that too much time had passed since the songs were written. But even if Johnson were granted full partnership in those compositions, there is still the unmistakable signature Chuck Berry guitar riff and, of course, those glorious lyrics. You could have every other element in place—the rock ‘n’ roll myth, the prison time, the trademark duck-walk and the ringing guitar solos—and it is still not half as interesting without the magnificently idiosyncratic lexicon of Chuck Berry’s poetic rock ‘n’ roll lyricism. While Berry’s subject matter was oft-imitated, his distinctive lyrical style was pitched at such a high level of originality—with “Cool-a-rators,” “botheration,” and “motorvatin’,”—that it has proved in many respects impossible to follow.

In short, not enough attention has been paid to the sheer brilliance of Berry’s lyrical wit, and the deft, darting sound of those words in the air. In “Nadine (Is That You?),” behind a swaggering bass line and Johnson’s dancing piano, he sets off for the object of his affection:

“I saw her on the corner when she turned and doubled back

And started walking toward a coffee-colored Cadillac

I was pushing through the crowd trying to get to where she’s at

And I was campaign-shoutin’ like a Southern diplomat”

At one point in the film, Bruce Springsteen commends Berry’s evocative imagery, noting with a look of sincere amazement, “I’ve never seen ‘a coffee-colored Cadillac,’ but I know exactly what one looks like.”

Repeatedly, Berry seized on the metaphor of a car as representative of the pure instinct for American freedom. “No Money Down” neatly captures the vast scope of postwar American optimism (and consumerism), as a man drives down to an auto dealership, to trade in his Ford for a newer, slicker, faster, more luxurious ride:

“Well Mister I want a yellow convertible

Four-door de Ville

With a Continental spare

And wire chrome wheels

I want power steering

And power brakes

I want a powerful motor

With a jet off-take

I want air conditioning

I want automatic heat

And I want a full Murphy bed

In my back seat

I want short-wave radio

I want TV and a phone

You know I gotta talk to my baby

When I’m ridin’ alone”

Though Berry often censored himself for radio airplay (“Brown-Skinned Handsome Man” became “Brown-Eyed Handsome Man,” and Johnny B. Goode’s “colored boy” became a “country boy”), he probably deserves extra credit for getting a song played on the radio in which the protagonist—an African-American no less—boasts of a foldout bed in the backseat of his car.

Even in an apparent one-off like “Dear Dad,” in which the hapless student imploring his father for a new set of wheels turns out in the last line of the song to be Henry Ford’s son, Berry elevates the joke in a blizzard of idiomatic language and keenly-wrought imagery:

“Last week when I was driving on my way to school

I almost got a ticket ‘bout a freeway traffic rule

It’s now a violation driving under forty-five

But if I push to fifty this here Ford’ll nosedive

Dad I’m in grave danger, out here trying to drive

The way this Ford wiggles when I’m approaching 45

I have to nurse it ‘long like a little stubborn pup

The cars go whizzin’ by me dad look like I’m backin’ up”

Berry possessed an arsenal of songwriting talents, and did not always have to be verbose, or comic. In “School Day” there are 24 lines of sparsely constructed narrative tracing a typical day in the life of a high school student, through a morning of studies and drudgery, a bustling, hurried lunch and an afternoon of more classes. The three o’clock bell sends the students out to the streets and to the nearest diner, where they put their money into the jukebox, all leading up to the ringing declamation of “Hail! Hail! Rock ‘n’ Roll/Deliver me from the days of old….”

Certainly, Berry was not the only gifted songwriter in the rock idiom at the time. But even among his celebrated contemporaries—Lieber & Stoller, Buddy Holly, Doc Pomus & Mort Shuman, Fats Domino & Dave Bartholomew—his lyrics stand apart. At a time when rock ‘n’ roll was being dismissed as little more than juvenile delinquency set to a backbeat, Berry instilled the music with heart, an understated playfulness and an uncompromising intelligence. One could not hear the phrase “campaign-shouting like a Southern diplomat” without realizing that rock ‘n’ roll could contain multitudes.

And because of that, Bob Dylan could write “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” John Lennon could write “Imagine,” and Bruce Springsteen could make The River, which reimagined a rock ‘n’ roll album as the Great American Novel. Incontrovertibly, none of those things happen without Berry.

• • •

We’ve got to find a lawyer in the clique with politics

Somebody who can win the thing or get the thing fixed.

—Tulane, Chuck Berry

If Berry was an ambassador for the Brave New World, the signal frustration of his early career is that it could not arrive as fast as he had hoped. He was the first black performer to put a rock ‘n’ roll record on the pop charts, with “Maybellene” reaching the Top 10 in the summer of 1955. Yet that victory was muted by his discovery that disc jockey Alan Freed had taken a portion of the songwriting credit, part of the payola scandal that further sullied the reputation of rock ‘n’ roll music in the late ‘50s. Later, Berry performed on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand, reaching a much larger audience than he might have otherwise, but thirty years later, talking with Little Richard and Bo Diddley in a segment for Hail! Hail!, Berry still bridled at the restrictions placed on him because of his skin color, recalling “We couldn’t dance with the audience.”

Hackford chose to focus on Berry’s long racial struggle, filming a segment outside the box office at the Fox Theater, where Berry recalls he and his father being turned away when they tried to buy tickets to see A Tale of Two Cities, and later inside the theater, where he eloquently testifies to the grace and splendor of the theater, then reflects on the irony of his headlining performance later that night at the Fox, not far from the county courthouse, “where my ancestors were sold on the courthouse steps.”

He was the first black performer to put a rock ‘n’ roll record on the pop charts, with “Maybellene” reaching the Top 10 in the summer of 1955.

There is all this race consciousness, and yet Hackford neglects to feature what is arguably Berry’s greatest work, “Promised Land,” a road song that serves as an epic metaphor for the journey of black slaves out of the South and into the mainstream of American culture (in an apposite coincidence, the song was recorded on the very same day—Feb. 25, 1964—that Cassius Clay beat Sonny Liston for the heavyweight title). The song takes its narrator from Norfolk, Virginia, through the strife-torn South, where the Greyhound bus on which he is riding breaks down, prompting him to board a train that works its way “across Mississippi clean,” then down into the Southwest and, finally, traveling by plane now, into the promised land of California, in a final verse that pointedly evokes the Negro spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” Like many of his other songs, “Promised Land” works both as a standard rocker, but also as something far more complex and ambitious.

Berry’s personal journey proved problematic. After his first wave of great success, as his star and rock ‘n’ roll were both rising in the late ‘50s, he opened a club in St. Louis called Club Bandstand, which was unique in being one of the few interracial public nightclubs in the city in that era, serving as an oasis from the onerous racial segregation that troubled blacks and whites alike. Bo Diddley recalls in the full-length interviews on Hail! Hail! the absurdity of playing some concerts in the ’50s in which a rope ran down the middle of the audience, separating blacks from whites. “Stupidest thing I’d ever seen,” he muttered. It would not last much longer. Rock ‘n’ roll hastened the demise of Jim Crow, through its rebellious mythos, the tremendous value it placed on personal freedom, and the inclusive nature of its revolutionary spirit.

But the racial reconciliation did not work fast enough for Berry. He returned to prison in the early ’60s, after being convicted on a specious Mann Act charge, for transporting a 14-year-old Mexican girl named Janice Escalanti across state lines, while he was operating Club Bandstand. He must have begun his second stint feeling a keen amount of despair for all that had not changed. He earned his CPA degree this time around, and came out of prison in 1964 vowing he would not be fooled again.

Upon his release, he put out a string of magnificent rock ‘n’ roll songs—“Promised Land,” “Nadine (Is It You?),” “No Particular Place to Go,” “No Money Down,” “Dear Dad,” “Tulane”—that together suggested he had grown as an artist, and could keep doing so indefinitely. But none of these songs approached the commercial success of his earlier hits, and Berry soon tired of the studio process. While his work became the catalyst for a generation of British bands like the Beatles and Stones (Richards speaks with wonder in both his eyes and his voice of “the total sound” of Berry’s songs when needle touched vinyl), it was a far different story domestically, where Berry was dismissed as a ’50s anachronism, whose contributions were not celebrated so much as taken for granted. People bemoan the Caucasian rapper Vanilla Ice as a poseur for his heavily-sampled hit “Ice Ice Baby,” but what the former Robbie Van Winkle did to the Queen & David Bowie hit “Under Pressure” was no different than what Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Famers the Beach Boys, in “Surfin’ USA,” did to Berry’s “Sweet Little Sixteen.” After legal action, the band finally was forced to give Berry a co-songwriting credit on the song. (One of the songs for which, nearly 40 years later, Johnson would sue Berry for co-songwriting credit.)

Today Berry, at 81, is a hearty survivor, outliving his contemporary Elvis by more than three decades, and still playing a monthly gig at Blueberry Hill’s Duck Room in the St. Louis Loop. In the summer of 2007, he sat for a radio interview with Bob Costas, who asked the father of rock ‘n’ roll for the secret to his longevity. Berry, genial and elusive, chalked it up to “cool water and long walks.”

There is a touching moment near the end of disc three in the Hail! Hail! package, in which Berry, accompanied by a reverent Robbie Robertson on guitar, recites a lengthy poem he composed about the passing of time, of all the things that cannot be reclaimed, of triumph and tragedy and mortality. Hackford did not use any of it in the film, and one can see why—at several minutes long, it would have interrupted the flow of the picture. Yet it is a moving vignette, and watching the plaintive, unguarded Berry in these moments, we see his love for the language and sense some of the hard-earned wisdom of a man who came so far, and learned so much on the way.

In the end, there is something profoundly conflicted in Chuck Berry. His strict diction, formal dialect and lyrical rectitude (asked to name the song he wished he had written, he once cited the Everly Brothers’ “Wake Up, Little Susie”) make him seem, at times, almost prim. Yet this is countered by Berry’s alleged fondness for scatology, his reputation not merely as a philanderer but a dehumanizing one (who stooped to placing a secret camera in the women’s restroom at one of his restaurants) and an inordinate fascination with juvenile humor. It is one of the great ironies of music that Berry’s only No. 1 hit on the Billboard pop charts was the novelty ditty “My Ding-A-Ling.” Recorded in 1972 in London, at the height of hippie chic, the song at one point finds Berry, voice full of innuendo, remarking that he hears “two girls over here singing in harmony.” He then offers a kind of leering encouragement: “This is a free country! Live like you want to live, baby!” During that period, Berry embraced hippie culture, and began dressing in wide flared pants and loud, huge-collared silk shirts that he still favors onstage today. During their interview this past summer, he mentioned to Costas that he was fascinated with the hippies, but ultimately frustrated by them. “They were always trying to find out who they were,” said Berry. “And that mystified me. I always knew exactly who I was.”

Surely he did. But he has had better luck than the rest of us. Berry remains opaque, unknowable. One thing is clear. In the long struggle to get to the Promised Land, something deep inside Chuck Berry was broken—maybe it was heart, maybe it was his spirit, most probably it was his capacity for idealism —and the wound is perhaps too deep, even for the healing powers of rock ‘n’ roll. Which is a shame, because Berry’s music has sustained so many others. And his life itself has been a quintessentially American triumph.

Editor’s note: This essay was first published 2007 in Belles Lettres, a former publication of Washington University in St. Louis’s Center for the Humanities.