black or Black (adj.): of or relating to any of various population groups having dark pigmentation of the skin

My mom incredulously asks me why the doctors would suggest taking my grandfather off the ventilator if his heart and brain are still working. My mind marquees “bed shortage,” “medical violence,” “Black lives matter.” I respond “I don’t know” instead. My grandfather is not dying of coronavirus, but my grandmother might if she goes into the hospital to see him.

In the suburbs of St. Louis, two friends, one black and one white, are taking a walk in the night six feet apart. A police officer pulls up and tells the black girl she is walking too close. Only the black girl. He says he is responding to a report of a suspicious person. He is an essential worker. He has been essential since 1704.

• • •

black (adj.): marked by the occurrence of disaster

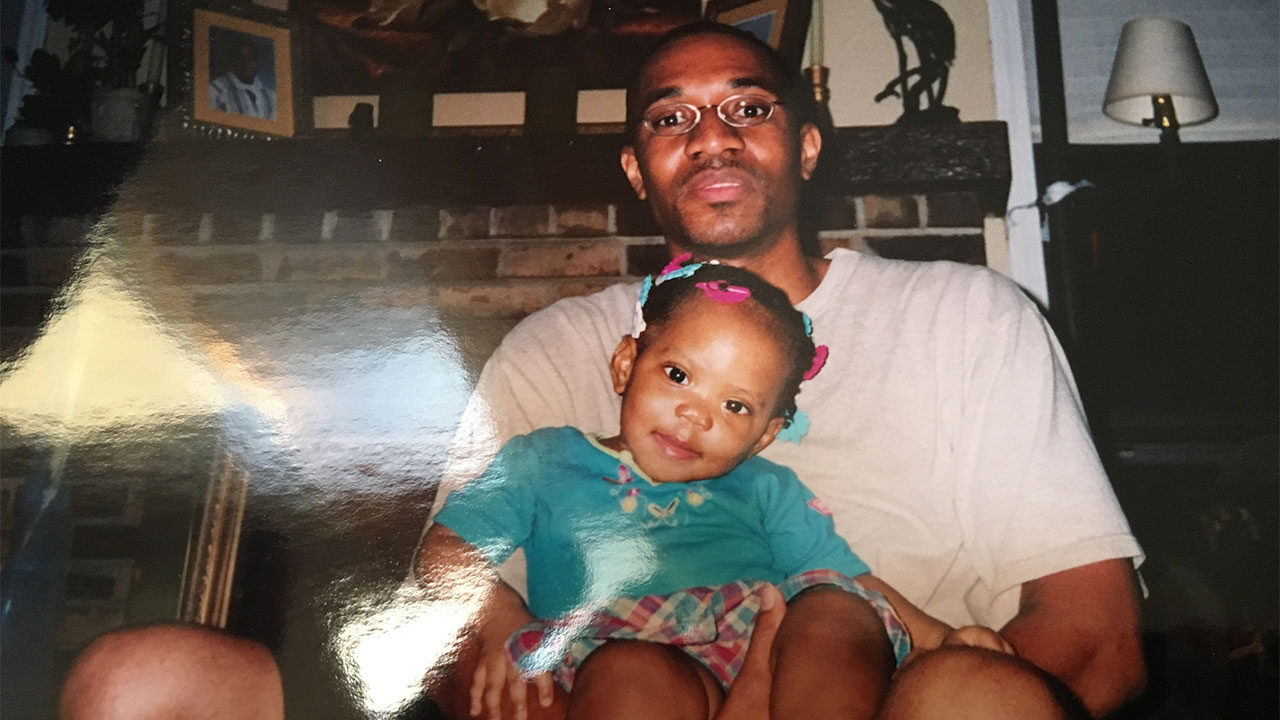

The distance I feel from my grandfather is greater than the 700 miles between Kansas City and Birmingham. It entails expanses, decades, religion, alcohol, dementia, fear, anger, and giving up. The distance from my father, however, as his shoulders sag lower and his eyes hang heavier, is sudden, new, and scarier than the texts I keep receiving: “dire condition – life support – blood clot – resuscitate – FaceTime – do.” My father’s week is marked by closed doors, long phone calls, and quick emergences to the kitchen for food. I do not know how to share with him in his grief. My father’s sister puts it best: “I have already been mourning my father for years.” There is no mourning for my grandfather left inside me. There is only guilt as I look into my father’s tired face, guilt as I scroll quickly past a COVID headline. My father is so, so far away from me now, just across the hall.

• • •

black (adj.): very sad, gloomy, or calamitous

I have just finished an essay over which I have agonized for days. I am walking into the kitchen. I am congratulating myself on my completion, feeling proud and relaxed. I see a pot of white flowers on the table—my grandfather is dead. How odd.

On Wednesday I help my father reschedule his flight: he must mourn with his family in July. It took five people and three days to convince him that April is too risky to fly. We do not know if it will be safe by July.

On Thursday I endure an exercise in convincing five elderly black religious relatives to stay at home: “God is our covering,” they argue. “Is He not other people’s covering?” I fume. I don’t need to have a philosophical debate on faith and religion right now. “I need you to stay at home.”

On Thursday I endure an exercise in convincing five elderly black religious relatives to stay at home: “God is our covering,” they argue. “Is He not other people’s covering?” I fume.

The brief, teary-eyed video appeal that my mom films and sends to my father’s family seems to work: my aunt texts us saying that they will not gather to observe Passover. But my other aunt has been going to the grocery store every day, sometimes twice daily. And just a week prior, several elderly relatives, one severely immunocompromised, had gathered in my grandmother’s house to mourn my grandfather. And two days after that, a group of relatives met for Bible study with another immunocompromised person. “We have to hurry and get home!” my aunt texts. “The stay-at-home orders take effect at 5:00!” My family thinks they can outrun, outdrive, outpray a virus.

• • •

black (n.): a person belonging to any of various population groups having dark pigmentation of the skin; African American

“Fifty percent of people testing positive for coronavirus in Kansas City are black.” The Star’s headline stares back at me. I look away, gazing out the window at my neighbor’s house; the nurse is checking in again on Ms. Cookie and her husband. I remember Ms. Cookie stumbling out the house, hand over her chest, paramedics in masks spaced six feet away from her. I remember the four emergency vehicles at a different house on our street the week after an ambulance carried Ms. Cookie away. I remember the text which confirmed that Ms. Cookie and her husband had contracted coronavirus. I remember that my neighborhood is 37 percent black.

• • •

black (n.): total or nearly total absence of light

When I pull on my mask before getting out of the car, I smile at how I have accidentally put it on upside down. When I finally exit the car, my smile fades at how quiet the parking lot is. How empty the Walgreens is. How I will have to disinfect my change, the groceries, the bags, my clothes when I get home. How many police cars I have seen on the way here—more than usual.

I lay on my back and listen to Therapy for Black Girls, go through my third meditation, skim a short devotional reading. None of it is working.

I know I see police in my neighborhood more often now than I used to: one day two officers walk away from the house across the street from mine, another day officers walk around the back of a neighbor’s house before talking with him on the porch and leaving, another day an unmarked car cruises down our street. Ahmaud Arbery’s death was not COVID-related, but it is yet another burden that I try to press away, another headline I try to scroll by. I lay on my back and listen to Therapy for Black Girls, go through my third meditation, skim a short devotional reading. None of it is working.

Maybe this will make more sense when it is over. Maybe it will make less.

Note: all definitions taken from Merriam-Webster.