The 1970s had a lot in common with youth. When we’re young our optimism and idealism reach levels they may never see again; if our actions leave a little to be desired, our intentions are never better. And while the 1970s, on a national level, may have brought everything except cause for optimism—Watergate, the tragic, slow-drag end of the Vietnam War, long lines at the gas pump, the Iranian hostage crisis—our personal bent, perhaps in reaction to all that, was toward the feel-good, the loving acceptance of ourselves and those around us for who we were. If all that our 1960s activism had brought were the killings of two heroes (Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy) and the ascendance of a villain (Richard Nixon), well, maybe it was the personal rather than the political that mattered. The 1970s were famously described as the Me Decade, but the ethos was less about personal gain (that’s what the 1980s were for) than about being happier and better people. This was the decade that gave us Free to Be … You and Me (a 1972 recording with accompanying book, followed by the same-named 1974 television special, which promoted gender neutrality) and made a best-seller of Thomas Anthony Harris’s 1969 book I’m OK, You’re OK. Today the language may make us cringe, but it’s a dried-up and withered heart that doesn’t retain just a little of the sentiment.

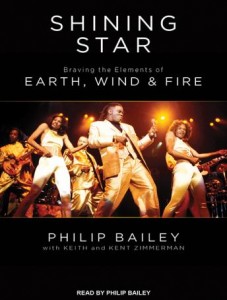

If you’re like me—that is, if your youth and the 1970s happened at the same time (I was six when the decade started, sixteen when it ended)—you may have a particular soft spot for the period. You may also feel that nothing captures that time better than the music of Earth, Wind & Fire. (The band took its name from the classifications of their members’ astrological signs: there are three earth signs—Taurus, Virgo, and Capricorn; three water signs—Cancer, Scorpio, and Pisces; three air signs—Gemini, Libra, and Aquarius; and three fire signs—Aries, Leo, and Sagittarius. No one in the original band had a water sign.) In my all-black neighborhood in that era of the 45-RPM single, a time and place in which soul and funk ruled, my first album—and EWF’s most celebrated work—was That’s the Way of the World, which represented something different in its music, lyrics, and general feeling. Here was a black group whose addictive melodies featured African sounds and jazz/rock fusion guitars (I couldn’t have put it that way at the time, but I knew something was unusual); other black acts encouraged us to think (Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” Stevie Wonder’s “Living for the City”), and many of them encouraged us to feel good, mainly through love songs too numerous to mention, but Earth, Wind & Fire did both. The fold-out cover said it all: black-and-white photos of the group’s members in the Afros and the bell-bottom pants of the day, each one just being himself. According to the very enjoyable autobiography Shining Star: Braving the Elements of Earth, Wind & Fire, by EWF lead singer Philip Bailey with Keith and Kent Zimmerman, each member was photographed while on a trampoline, the images (minus the trampolines) set side-by-side. One of the few standing still is the bearded leader and drummer, Maurice White, who holds his hands apart with a glowing smile that seems to say, What a joyous thing. And then there were the songs’ lyrics: “Be a giant or grain of sand/Words of wisdom: ‘Yes I can’”; “Stop! Look what’s behind you/Fame and love gonna find you/We’re just here to remind you/Yearn and learn is what you do.” Who wouldn’t want to think so? If a day passed in the summer of 1975 when I didn’t play that album, it’s a day I don’t recall.

Other black acts encouraged us to think (Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” Stevie Wonder’s “Living for the City”), and many of them encouraged us to feel good, mainly through love songs too numerous to mention, but Earth, Wind & Fire did both.

Nothing comes from nothing. (Nothing ever could.) The thoughtful lyrics and sheer musical invention of Stevie Wonder probably had an influence on Bailey and the rest of EWF, despite Bailey’s writing, “As I sought to forge my own musical identity, I made a conscious decision for the time being not to listen to one artist I dearly loved: Stevie Wonder. So deep was my admiration for him that I was sure that if I listened to him too much, his styles would rub off on me and I would end up perceived as a pale imitation.” While there was arguably some rubbing-off anyway, I would contend that it possibly worked two ways: the exuberance of tunes like “Sir Duke” and “I Wish” from Songs in the Key of Life, released the year after That’s The Way of the World, just may have owed something to EWF. The Isley Brothers’ work of the era, which boasted equally innovative melodies and had lyrics just as thoughtful as EWF’s, if not more so, may have exerted some influence, too (Bailey doesn’t say); but while the Isleys could tend to admonish (“You ain’t me and I ain’t you/Check out the difference between the two”), Earth, Wind & Fire stood out with their positivism.

EWF had many good years—some of the best, in fact, of any band that ever played. Bailey, who wrote or co-wrote many of EWF’s biggest hits and shared principal singing duties with White, details those years in Shining Star, which covers both his own story and the history of the group. Bailey was born in 1951 in Denver, the son of Elizabeth Crossland, a single, loving but emotionally unstable mother. From a young age he witnessed his mother’s equally unstable relationships with a number of men, including Bailey’s father. Eddie Bailey was already married when his affair with Elizabeth produced Philip Bailey’s older sister, Beverly; after Eddie’s wife rather magnanimously invited Elizabeth and Beverly to live with her, Eddie, and their kids, Eddie and Elizabeth continued their affair, and along came Philip. Eddie wavered between his two families before moving out of the state with his wife and their children and dropping out of Philip’s life. That romantic chaos would be mirrored in Philip Bailey’s own adulthood.

Bailey was sickly and nonathletic as a young boy. But he discovered early on that he was gifted musically, and he sang and played percussion in the church choir and other groups, with his mother’s blessing, beginning when he was a preteen. While performing with a Denver-based group called Friends & Love, whose music mixed soul, rock, and jazz, the 19-year-old Bailey caught the attention of the deejay and record promoter Perry Jones; Jones later recommended Bailey to the leader of another multi-genre group: Maurice White of Earth, Wind & Fire. (White had been a jazz drummer with the commercially successful Ramsey Lewis Trio, which is surprising only until you consider EWF’s fusion leanings. Indeed, Lewis recorded an album called Sun Goddess in 1974 with White, Bailey, and other members of EWF.) EWF, which had released its eponymous debut album in 1970 and a successful follow-up, The Need of Love, the following year, was suffering growing pains. White had what he called a “Concept” in mind for the band—“one that would signify universal love and spiritual enlightenment,” in Bailey’s words—but he suddenly had no band to carry it out, since (in a sign of things to come) most of the other members had walked out, complaining of White’s autocratic style. Taking on new members, most notably Bailey, EWF released more albums, including Head to the Sky (1973) and the gold record Open Our Eyes (1974), along the way enlisting the invaluable services of the producer Charles Stepney and getting hard lessons about performing. (“Getting our asses handed to us” by Parliament Funkadelic, who took the stage after EWF one night in Washington, D.C., “was the best way for us to learn to toughen up our sound,” Bailey writes.)

Already successful, EWF became a legend with That’s the Way of the World (1975), which went double platinum, won a Grammy for best R&B performance by a group, produced a single (Bailey’s “Shining Star”) that topped both the R&B and pop charts, and included the signature ballad “Reasons.” (The album fared considerably better than the same-titled movie, starring Harvey Keitel, for which the songs provided the soundtrack.) The group’s great run continued with Gratitude (1975), the live album that introduced the hit “Sing a Song”; Spirit (1976), including “Getaway”; All ’n’ All (1977), with “Serpentine Fire”; The Best of Earth, Wind & Fire, Volume 1 (1978), which introduced “September,” possibly the sentimental favorite among the group’s songs; and I Am (1979), with “Boogie Wonderland” and “After the Love Is Gone.”

There was real joy in those songs. They were danceable, yes, but not in the way of the many disco hits of that era that were calculated to get you on the floor. (Donna Summer’s work comes to mind.) “When you feel down and out/sing a song, it’ll make your day”—who couldn’t get behind that sentiment, or respond to the good will at its heart? With EWF songs, dancing was not so much the point as it was a by-product of their infectious good feeling. I remember being at a junior-high dance when “Sing a Song” began to play, and a shout of pure happiness went up from the kids on the floor, one that was no doubt echoed at parties around the nation.

Things could not have been going better for Earth, Wind & Fire, which is usually the time—though few ever do it—to start worrying.

Like youth, the 1970s could not last forever, actually or metaphorically. In our quest for self-acceptance, we may have found certain things about ourselves hard to take, and perhaps we discovered that in some cases, accepting who others were meant realizing that we didn’t want to be around them. Meanwhile, fame didn’t find us, as the song promised it would—didn’t, in fact, seem to be looking particularly hard. Love may have found us, decided it had the wrong person, then left again, repeating the mistake once or twice before coming back for good, or not.

Bailey tells the story mostly with mature self-awareness but occasionally with a breathtaking lack of it. He recalls having to learn, once his own stature within EWF grew, not to be so hard on other members.

For Earth, Wind & Fire, the 1980s brought difficulties from within and without. Beginning with the financially unsuccessful album Faces (1980), released four years after Stepney’s death, “technology would profoundly influence Maurice’s methods of production, and the new era of drum machines and polyphonic synthesizers would greatly affect our communal vibe as a studio band,” Bailey writes. Between that and the release of several more flops, EWF’s camaraderie fell apart, as “the band had effectively become glorified session players for Maurice in the studio.” Another issue was that “EWF was an archetypal band of the 1970s, and yet we didn’t understand the dynamics of the 1980s. Michael Jackson understood the 1980s.” (So did Prince, who was an EWF admirer but whose work had less to do with love than with sex.) “Maybe the Concept didn’t apply anymore,” Bailey muses. “The world wasn’t about peace, love, and positivism. The 1980s were about economics and music for cold hard cash.” The Concept certainly didn’t apply to other members of EWF: after keeping most of the cold hard cash for himself, in 1983 White basically told the band to get lost. Subsequent attempts at reunion albums and tours were disastrous, and many years would pass before Earth, Wind & Fire was a successful band again.

Bailey tells the story mostly with mature self-awareness but occasionally with a breathtaking lack of it. He recalls having to learn, once his own stature within EWF grew, not to be so hard on other members. That honest self-appraisal goes missing when he recounts flatly telling his wife, who was pregnant with their third child, that he was having a baby with another woman: “Janet threw a huge fit, so I put her out on the front porch to cool off.” Of course you did! The nerve of that woman! (This, by the way, was after Bailey became a born-again Christian.) He does write later that he is “not proud of my past extramarital exploits,” and the end of the book finds the twice-divorced Bailey, with a slew of solo albums under his belt, making a seemingly genuine attempt to face his shortcomings.

Meanwhile, as younger listeners discovered the music of Earth, Wind & Fire, the band found its footing again. EWF has since toured successfully (though without White, who announced in 2000 that he has Parkinson’s disease) and released more albums, most recently Now, Then & Forever (2013), which features new material. “A new generation of music lovers had been getting turned on to us,” Bailey writes, though no doubt there are plenty of older ones, too, hoping to recapture something of their optimism, their idealism, their youth.