Late 20th-century American suburban lore dictates that if the oldest, or only, child of any family is introduced to cool music, it is the cool older brother of a friend who makes introductions. In the case of my introduction to David Bowie (1947-2016), however, the single mother of a best friend did the deed.

Rough-housing in the middle of her living room, she asked that we pipe down so she might hear the strains of “A Space Oddity” over the radio.

“This is one of my favorite songs,” she said. “One day, it might be yours!”

Was it ever. It would be a lie to say that, listening to the story of Major Tom in that dusty, sun-lit room, my heart was first won. It took a few years afterward for the introduction to gel, for a 10-year-old kid to hear that same song three or four more times for the hook to latch firm. Few of us grow up in an instant.

But it is God’s truth that, once the testosterone-fueled haze of boyhood wore off and rock music came into adolescent view, I seized every Bowie album in the then 1978 catalog. I would have also dyed my hair shock-red and pierced my ears, had not my mother threatened to throw me out of the house if those fashion threats were carried out.

… because you knew David Bowie, you learned that rock music never stood still. Because you knew David Bowie, you could tolerate the schoolyard bullies who called you “fag” for owning a copy of Ziggy Stardust or Station to Station. Because you knew David Bowie, you bought albums like Eno’s Here Come The Warm Jets after buying Low. Because you knew David Bowie, you had an education.

Growing up in late 1970s Salt Lake City meant you knew very little of the outside world. But because you knew David Bowie, you learned that rock music never stood still. Because you knew David Bowie, you could tolerate the schoolyard bullies who called you “fag” for owning a copy of Ziggy Stardust or Station to Station. Because you knew David Bowie, you learned that being gay or bisexual was a point of creativity and celebration, not shame. Because you knew David Bowie, your mother could take you (oh so reluctantly) to your first R-rated movie to see Christiane F (1981).Because you knew David Bowie, you learned about modern European history through a song like “Heroes.” Because you knew David Bowie, you bought albums like Brian Eno’s Here Come The Warm Jets after buying Low. Because you knew David Bowie, you had an education.

Where you lived did not matter. What mattered was where your mind was in relation to the artist who arguably did more to alter, even invent, modern rock and pop culture than almost any other figure.

Since the icon’s Jan. 10 death, there has been no end of praise for the ways in which Bowie made the world a safer place for weirdoes, freaks, misfits and miscasts. Dick Cavett said it best, introducing the star to his television show’s November 1974 studio audience:

“He’s the only person I know who has appeared the same year on the best-dressed-men list and the worst-dressed-women list. Rumors and questions have arisen about David such as ‘Who is he? What is he? Where did he come from? Is he the creature of a foreign power? Is he a creep? Is he dangerous? Is he smart, dumb, nice to his parents, real, a put-on, crazy, sane, man, woman, robot? What is this?!’ His fans have seen him do almost everything but sit and talk, which they will see tonight. It will be a first for them. On this concert tour here is still another ‘David Bowie’ … ladies and gentlemen, David Bowie!”

All true. But it is not just cliché to remind people that Bowie was a shape-shifting “chameleon” with a penchant for theater, that every detail of his changing persona was integral to his seamless, flawless whole. It is painfully clichéd.

There is great fun to be had arguing with fans about the relative merits of Ziggy vs. Thin White Duke vs. “Plastic Soul.” But not as much fun as arguing over which colleagues and collaborators best fueled Bowie’s creative engine. Was it the masterly, yet raucous, finesse of Mick Ronson, the greatest—nay, only?—Mormon alcoholic guitarist to grace a stage? Or did the funk influences of Chic’s Nile Rodgers bring out Bowie’s most honest, relaxed—not to mention lucrative—persona for the worldwide 1983 smash LP Let’s Dance? The sure way to end any arm wrestle over the matter was to throw down Brian Eno, if not Bowie’s finest artistic collaborator then surely his best known. Then there is the persuasive contingent in favor of producer Tony Visconti, who did more than anyone to shape the sound of Bowie’s “Berlin Trilogy” albums, all while maneuvering around, over and under the star’s voracious cocaine appetite.

Yes, all great fun.

For a decade in which rock music was reaching its zenith as a profitable business—the 1970s—it is staggering to consider the sheer number of risks Bowie took, without any hint or appearance that he was risking anything at all. When Michael Jackson, for a time Bowie’s only serious commercial competition, did or said something eccentric or offbeat it seemed cause for concern, even crisis. It is worth remembering the shock sent throughout the music world when Bowie proclaimed in 1972 “I’m gay and always have been.” That alone, at that time, was more shocking than saying you were, in fact, an alien from outer space. But Bowie had claimed that too, of course. Because Bowie’s sexual identity was declared in the musical and theatrical context of his own making, the impact was seismic, but at the same time strangely muted. Maybe it lost him fans. There’s no question it branded his middle-America fans “fags” by association. But it implicated and announced “queer” culture for the better, in ways felt ever since. Regardless, and true to form, Bowie switched identities soon after. No longer strictly gay, he took up the (at that time) almost equally shocking pursuit of dating black women.

It seemed a tad too predictable to keep on behaving in unpredictable ways. The more some entertainers change, the more they remain the same. The complaint might have been valid if Bowie’s music was not so damn fantastic.

In hindsight, it is easy for cynics to point to all this as part of a calculated game. Behaving in unpredictable ways, after a while, becomes predictable. The more some entertainers change, the more they remain the same. The complaint would have been valid if Bowie’s music was not so damn fantastic. For die-hard fans, it is tempting to believe, or even insist, that if Bowie had never donned theatrics or cared at all about fashion, he would have been just as famous.

His voice alone, whether singing or simply talking, was enough to command a room. A cutting, continuous line of fine-grained textures, you never noticed when, or even if, he crossed into falsetto. Austere and at once full, resigned yet also defiant, Bowie’s voice, far more than his visual persona, was his signature. He could wield it as a precision instrument, as in the breathtaking “Lady Grinning Soul,” and also command it into something altogether grotesque and even hunchbacked. In songs like “It’s No Game” or “Scream Like A Baby,” it seemed he was singing behind dungeon walls. He could sing a rhyme as inane as “Hot Cross Buns” and make it sound sinister or profound, in equal turns.

Bowie borrowed sounds from German electronic music, an early lyric sense from Bob Dylan, the majesty of Scott Walker, the beat of Philadelphia soul, and the atonality of modern jazz. He tore a radical literary page from renegade writer and St. Louis native William S. Burroughs to write song lyrics from cut-up, rearranged words. Mike Garson, the American jazz musician who laid down the famous, atonal piano solo for “Aladdin Sane” at Bowie’s insistence, has said he still receives emails about his contribution. “I always tell people that Bowie is the best producer I ever met, because he lets me do my thing,” Garson once said.

There were times when he borrowed too overtly. “Red Sails” sounds too similar to Harmonia’s original “Monza (Rauf und Runter),” and “Starman” cuts too close at times to Marc Bolan’s “Hot Love.” But far better to fault a musician for being too inclusive of others’ work, than to shut out the larger world. Bowie opened his door wide, incorporating influences into songs and sounds so spell-binding you left your bedroom stereo convinced Bowie somehow originated all of it.

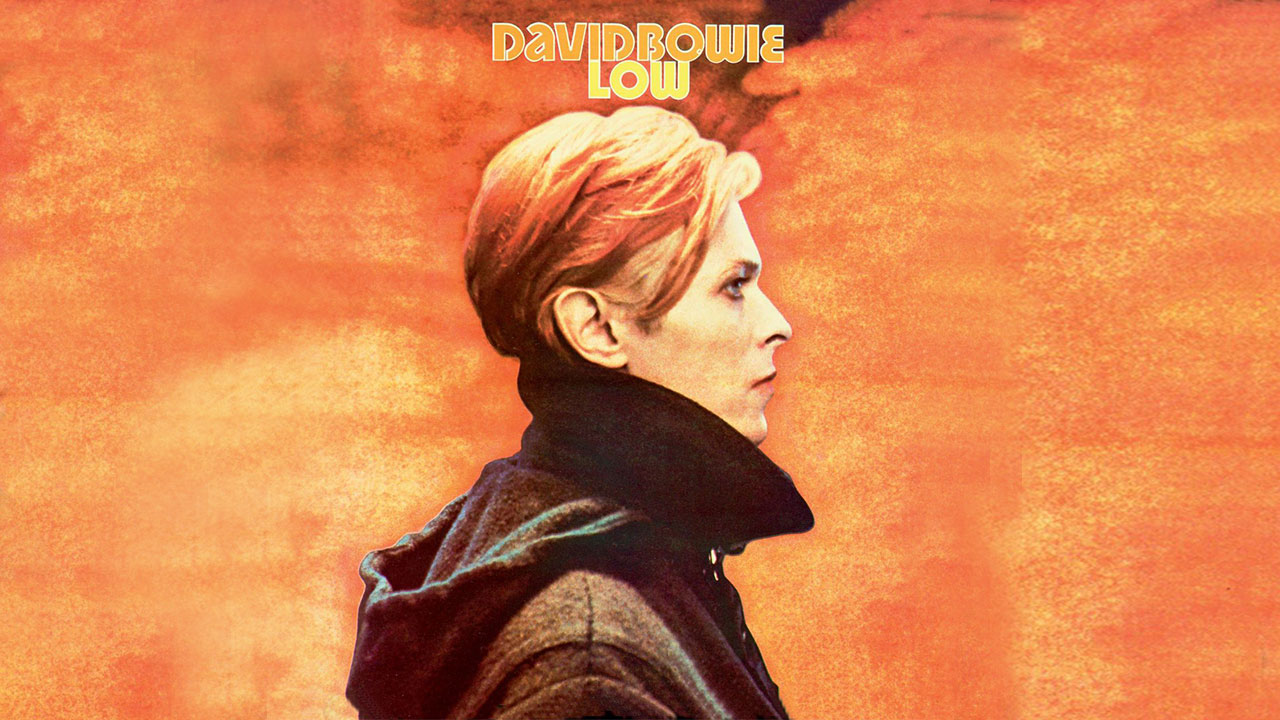

The greatest musical curveball he ever lent his name to was the second side of his 1977 LP Low. After a first side of short, dense, synth-laden songs about crashing cars and careers in other towns, you turned the record over in anticipation of more of the same, only to be greeted by something entirely different: four dirges as grey as Eastern bloc commie concrete where Bowie sings not one word, but sometimes sings eliding notes and chants across lumbering, shimmering soundtracks. “Did I just listen to David Bowie?” you ask in disbelief. “But of course.” His best music always pointed the way to new centers of gravity.

Die-hard fans tend to dismiss anything he produced after the 1980 LP Scary Monsters. After that, it was almost traumatizing to watch as Bowie wasted his time strutting through music videos with Mick Jagger, or churning out the clearly sub-par tunes of Tin Machine. Robert Smith, singer and lyricist for The Cure, once remarked it would have been better if Bowie had died in a car crash not long after the 1977 release of Low.

Such snipes said more about Bowie’s failure to clear his own bar, than about Bowie’s talent per se. And truth be told, as fine as his last album Blackstar is, there is something troubling about settling for biblical metaphor in the song of “Lazarus.” The master of changing personae resorts instead to a miracle of God? Say it ain’t so!

But disappointment is reserved only for artists who take us, not to one summit, but several, for sounds and visions of unparalleled fascination. Bowie did that with style to burn, always with wit in his eye, and always, as in the end of “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide,” offering up his hand. Or, as he said, “Just turn on with me, and you’re not alone.”