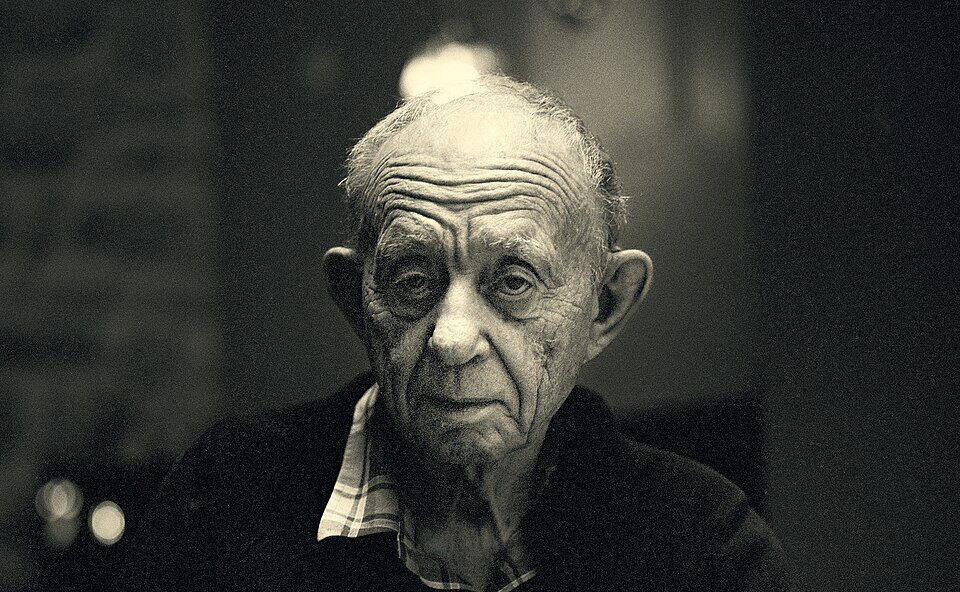

Bob Putnam, My First Man, Is Gone

By Chris King

August 27, 2024

When I prepared my reading for the farewell poetry performance at the Way Out Club in July of 2021, I pulled only from my chapbook Shape of a Man because it occurred to me that Bob Putnam, co-owner of the club, was perhaps the first man I ever knew.

I was old enough to be a man when I met Bob Putnam at age 19, but I really was not one yet. I had not known my father well. My grandfathers were dead or gone when I came along. I had some uncles, but they lived far away or were otherwise distant. I had just spent a long year in the U.S. Navy before going AWOL, mostly with U.S. Marines, but got to know none of those men. I was a couple of years away from meeting the college professors— both men—I would come to know well. As I got to know Bob Putnam by talking to him for hours on end at his used bookstore on the Delmar Loop, 20th Century Books and Ephemera, I was getting to know perhaps my first man.

Though Bob was old enough to be my father and he nurtured and supported me, as he did for hundreds of other young creative artists, I would not say he was a father figure. I would expect a father to be an authority figure. Bob was an anti-authority figure. This first man for me was a passionate advocate for freedom—of speech, especially, but also of act.

What would eventually become the Way Out Club started with Bob setting up a mic and amp on the sidewalk outside of his book shop and scheduling poets. I remember Bob scheduling storefront readings around the freedom of speech, for Banned Books Week and that sort of thing, and he cultivated the idea that you could say or do anything at his open mic. I have emptied many rooms (and sidewalks) with my more edgy and offensive material, but Bob was the rare show promoter who would rush up to me after a performance most excited about the piece that had chased away the most people.

I have a special fondness for the memory of Bob Putnam as I first met him, when he was still struggling to become free himself. There is such poignancy to someone who is still emergent, still inchoate. Bob was still married to Lori Putnam, who owned and operated the bookstore with him. He was still mixing paint at the Chrysler plant. (There was still, for that matter, an operational Chrysler plant in St. Louis County.) I have known a number of quirky hipsters who owned freaky little clubs, as Bob would come to do with his next wife Sherri Lucas, but I have only known one dyslexic guy who mixed paint at a Chrysler plant and owned a used bookstore with “Ephemera” in its name where he hosted Gerard Malanga.

That was a sight to see, Gerard Malanga in residence at 20th Century Books and Ephemera. I still had everything to learn about everything, but Bob did his best to explain this obscure counter-culture legend who had left Andy Warhol’s Factory just fifteen years before—that now seems like a short time—after fronting the Velvet Underground in the Exploding Plastic Inevitable, writhing around with a leather whip. I was just then beginning to encounter the academic version of writer in residence, which feels so dusty and shut in, nothing like this bright, wide-window bookshop that fronted on a Delmar Loop that was still a little scary then.

Bob started to whisper that he was seeing on the side his supervisor at the Chrysler plant, who turned out to be a hip and sexy Black woman. Sherri Lucas soon would help Bob get his poetry readings off the street and into clubs for one-off open mic nights and finally into a room of their own, the first Way Out Club on the west end of Cherokee Street (which had not yet started to come back from ruins).

I played a small role in that transition. In part inspired by Bob’s antics in front of his bookstore, I started putting together benefit shows for progressive causes that mashed up poets and musicians. I hatched that idea with an exchange student at Washington University from Shakespeare’s hometown, Sean Hilditch, but it briefly blossomed into an arts organization called Single Point of Light that included Bob Putnam. Most of what we knew going in we learned from Bob, but what we all evolved together looked a lot like what would soon take the stage at the Way Out Club.

I have two sets of vivid memories from the first Way Out Club on Cherokee Street.

I co-founded a Hootenanny there that flourished for years. I remember local rocker Mark Stephens (Boorays, Highway Matrons, Accelerando) performing a new song, “I Need a Girl,” at an early Hootenanny. As Mark finished his song, crying out into the club “I Need a Girl,” Bob Putnam was waiting, holding up the club’s phone. The call was for Mark. It was a girl, a woman, Sunyatta Marshall. Immediately she was sitting by Mark’s side. That was the closest thing to song as magic I have ever seen. (Mark and Sunyatta would go on to start and dissolve several bands and one marriage; Sunyatta McDermott now leads Cave of Swords.)

During the heady early days of the Way Out Club, I was spending a lot of time at an intentional community (hippie commune) in the Missouri Ozarks called East Wind. Passing guitars around East Wind campfires, I hit upon the idea of inviting a band of communards the five-hour drive up from the Arkansas line to open for my band in St. Louis. The Way Out Club was the obvious and perfect place to book Greenman Strathlick opening for Three Fried Men, and Bob loved the idea. Greenman Strathlick—hippie commies belting out sea shanties, led by a Vietnam veteran corpsman playing an Irish hand drum—had this unique presence that was both earthy and otherworldly. That vibe, incipient in the early Way Out Club, was further seasoned by these shows.

When I was living in New York, Bob and Sherri moved their club to the corner of Jefferson Avenue and Gravois Road. When I came home and went to shows there, I found the new location dismal. My memories of Bob from the first Way Out Club are of him beaming at song magic; from the second location, I remember Bob bolting out the front door onto Jefferson with a baseball bat to chase after someone committing one of the ubiquitous car crimes.

Freedom of speech and act reigned at the Way Out Club to the very end. As I looked around the club the night of that final poetry reading, I enjoyed the welcoming spirit of “anything goes” that Bob and Sherri always practiced, projected, and protected. Most memorably, David Wraith began his performance poem about Michael Jordan garbed for a game of hoops, and ended it naked as Michael Jordan the moment he was born.

There are now many places in St. Louis that embrace people who do not fit into comfortable categories, but the Way Out Club flew its freak flags proudly when it was much more lonely, if not dangerous, to do so. On its last night of live poetry, the Way Out Club sheltered and nurtured people of every shape and hair color, hovering between genders and personae, interracial and intergenerational lovers, gaily polyamorous groupings, and, very importantly, some lost souls barely hanging onto their grip of being here at all. They, especially, were Bob Putnam’s people. Bob’s passionate faith in the most fragile lengthened many lives.

Not all of Bob made it to the end of the Way Out Club. As he explained from the stage that last night of poetry, much of his memory was gone by then, lost to dementia. Those bright eyes that had blazed across a book counter at me 35 years before looked right through me that night without seeing his old friend. I remembered his excited scooting out from behind the counter at 20th Century Books and Ephemera to find for me a new used book that he knew I would treasure. This dyslexic man who mixed paint at a Chrysler plant brought more joy and insight into sharing the mysteries of books than almost all of my professors. Now that bright mind, that great man, my first man, was drifting away.

The Way Out Club went out of business after 27 years, which was exactly half of my life at that time. Now, as of today, August 26, 2024, the rest of Bob Putnam has gone from the face of this Earth.

It was strange, the night of that last poetry reading, to be so old yet still feel like we needed this odd assemblage of fellow humanity that Bob and Sherri brought together to be ourselves. I was proud of us all for making it that far. I felt like the sum of all of my past transgressions and experiments, yet probably not beyond my last ones. I felt then that new risks to take, new mistakes to make, more awkward phases of growth into the unknown lie ahead. I think of a wild light in the eyes of Bob Putnam, a paint mixer from the Chrysler plant peddling used books on the Delmar Loop, raving about a line of poetry—“Sunlight breaks at the edges of our blind spot,” Gerard Malanga wrote this, “This is exactly the way we want it”—and I feel that way today.