Art, Chickens, Goats, and Getting a Chance at a Desert Ranch

Artist Carole Alden left prison determined to live on her own terms. Nature stood in her way.

By Stephen Dark

November 22, 2025

Carole Alden’s 80 acres in southwest Utah afford a 360-degree vista over 50 miles of desert sagebrush and distant mountains—uninhabited, just how she likes it. Night reveals the only evidence of humanity emanating from the few lights of hamlets Beryl and Newcastle to the south.

But on June 20, 2025, 65-year-old Alden’s view was down to 50 yards. Fifty-mile-an-hour winds had driven wildfire smoke into the Escalante desert basin, once an inland ocean and her home for three years. All she could make out from the off-grid circle of broken-down trailers, homemade chicken coops, and shelters she had gathered for her 200 chickens and the rest of her farm-yard menagerie, was the dim outline of a mailbox she had cemented into the ground a year ago.

With so little visibility, she had no idea how close the fire was. The only way she would know was at night if the orange-red glow of the fire–then 85 miles away–announced its imminent arrival.

Visibility was not her only problem. She struggled to breathe due to her asthma, and her sinuses would not stop bleeding. The animals were also visibly panicking, as though they felt the end was close.

Alden hated to leave them, but there was no time to round them up on her own. They were unpenned, so she hoped their instincts would drive them away from the flames if the fire reached the farm. She had already filled containers with water hauled from a spring six miles away. At least they had plenty to drink.

She got in the truck with an abandoned baby goat she was nursing. As she drove off to stay with friends in town, she hoped the authorities had fought hard enough to save rich people’s vacation homes near the fire’s start in Pine Valley that they would shut the fire down. If it broke into the desolate flatlands, they would let it burn, along with what she had christened The Last Chance Rooster Ranch.

And the winner is …

Alden’s fears for her animals kept her awake that night. Losing her home not so much. It was not as though she hadn’t lost everything before. When she “fished in”—what inmates termed “first-timers’” arrival in prison—in July 2007, she had been stripped of everything: identity, clothing, medications.

In exchange, she received a number. But when Alden, a recognized regional artist before she had gone inside, learned she was being released after serving thirteen years for killing her abusive third husband, what she grieved losing most, at least when it came to the material world, was her fish house.

“‘The Fish House”’ was a crocheted, doormat-sized mobile home shaped like a deep-sea fish. She created it in 2017 to show her five adult children and the grandchildren, whom she barely knew, what her post-prison life would look like. Akin to a dollhouse, the creation had one side cut away to reveal her vision of vehicular domesticity: a jacuzzi-tub bathroom in the tail, a kitchen with hydroponic tomatoes growing by the window, bench seats, and little cups of coffee.

Alden planned to transform a live-in trailer into the fish house to travel the country. She also hoped to work with domestic violence survivors, providing therapeutic art classes.

One of her daughters entered “The Fish House” into the 2018 Utah statewide annual art contest—against her wishes. But “The Fish House” won “Best in Show,” a thousand-dollar prize, and the state paid $2,500 to add it to its permanent collection.

Leviathan dreams

Alden’s passion for prehistoric fish—which a millennium ago roamed the bottom of the Escalante Basin’s ocean seabed—went back to when she was three years old. Back then, she dreamed of gloomy depths pierced by fragile beams of sunlight and vast prehistoric fish brushing past her, their iridescent blue scales glinting in the murk. They protected her against predators. In their presence, she felt calm and safe, feelings she sought to reclaim all her life.

Decades later, those same dream monsters would inspire her early career in the Intermountain West as a self-taught artist. At first she worked with clay and bronze to breathe life into her whimsical creatures. She welded metals and employed fabrics and plastics to build truck-length dragons and prehistoric sea creatures.

Her monsters, rearing up in wry menace, captivated art festival curators and visitors. She taught sculpture workshops and spoke at universities. Along with twenty-four other state artists, she exhibited in “Out of the Land: Utah Woman” at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC.

When Alden went to buy the steel she needed to build a 96-foot dragon for the June 2006 Utah Arts Festival, locals at the store in her hometown of Delta belittled her and her artistic ambitions. Having built the dragon and moved it onto a bed she would tow to Salt Lake City, she stopped at the store to show it to the naysayers before getting on the highway.

She dreamed of gloomy depths pierced by fragile beams of sunlight and vast prehistoric fish brushing past her, their iridescent blue scales glinting in the murk. They protected her against predators. In their presence, she felt calm and safe, feelings she sought to reclaim all her life.

“God damnnnn,” was the admiring response.

She launched the dragon, complete with a yellow-and-green throat and pink-webbed wings, onto a pond outside the downtown Salt Lake City Library. It was a mesmerizing centerpiece for the city’s largest arts festival. For Alden, the sight of the dragon floating on the pond felt triumphant.

Just a few weeks later, her life fell apart. On July 28, 2006, after years of domestic abuse, Alden shot and killed her third husband, Martin Sessions. Fifteen months later, she was sentenced to fifteen years in the Utah State Prison.

The non-conformist

Freedom did not exist in prison. Not even as a memory. Alden’s daily reality was too harsh for that. She once awakened at 4 a.m. to meet the fixed stare of her cellmate, who said, “I like to watch you sleep.”

Co-existing with baby killers, child torturers, and hammer-wielding killers, she was hyper-vigilant, always aware she could not trust anyone around her, inmates or staff.

But Alden had one overwhelming drive from the day she shuffled into prison in ankle and wrist shackles: to create.

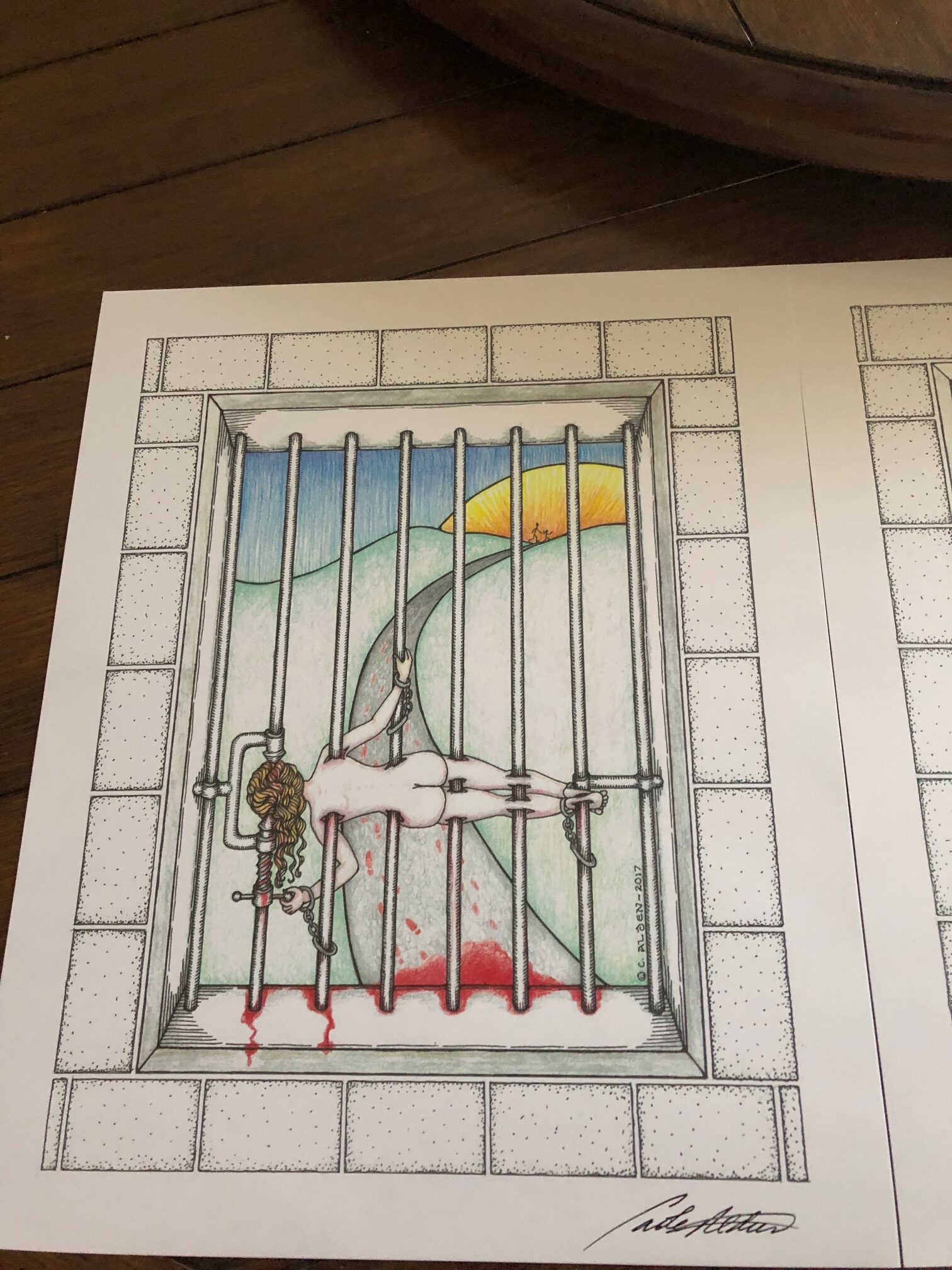

After being abruptly released in 2019, she discovered just how elusive second chances could be. Instead of bars and a six-by-four-foot cell, her confinement had become social, defined by society’s fear and loathing and the metaphorical “VF” branded on her breast: violent felon. Street medics call felons with violent-crime convictions “lepers at the gate.” You cannot get a job interview. No one will rent to you. Suspicious medical staff prescribe little more than aspirin.

Whenever it seemed she could not inch the Sisyphean boulder of her ambitions any farther up the hill, someone would offer a helping hand: an elderly couple, an online donor, some youths with a winch, or men who had known disappointment and wanted her to have the second chance she deserved.

In a way, Alden’s rugged artistic journey fits the stereotypical Western story of a heroine facing off against predators and climate. But with her criminal history, she carried an additional complication. Alden had to show society she deserved the second chance implicit in the idea of rehabilitative justice.

“You have to be able to prove that you’re not going to do ìt again,” she said. “That you deserve the risk someone is willing to take on your behalf.”

Even though she felt she had earned the right to a second chance, she did not get it. For all the lip service, society believed her sentence was a life sentence. “You never stop paying your debt to society,” she said.

So, Alden turned her back on society. She made a new life of off-grid survival and makeshift, self-taught veterinary care for her animals, hoping to build herself a shelter and return to her art. Such a hardscrabble life was not without its little mercies. Whenever it seemed she could not inch the Sisyphean boulder of her ambitions any farther up the hill, someone would offer a helping hand: an elderly couple, an online donor, some youths with a winch, or men who had known disappointment and wanted her to have the second chance she deserved.

The morning after she fled the wildfire, the smoke had lifted a little, so she set out at once for her land. After tarmac, gravel track, and miles of sand and dips, she topped a curve and saw her compound ahead. Galloping out to greet her came a herd of fifteen nervous goats. They turned and led her back home, an escort for a returning warrior—Joan of Arc or Boudicea—come again to meet the elements.

The killer beside me

One late night in September 2019, I pulled up to a downtown Salt Lake City bus stop, rolled down my window, and called out, “Carole?”

“Here,” squeaked a voice. The speaker was four feet eleven and heavyset from a decade of high-calorie, low-nutrient prison food. Her washed-out blonde hair was fading to grey, but her blue eyes slipped from exhaustion to cheeky charm in an instant. With her duffel bag leading the charge, she pushed through a crowd of white-shirted, returned missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, headquartered in Utah’s capital.

By then, Alden had been out of prison three months. As a journalist, I had gotten to know a number of people locked up for murder. She was the first I had met on the outside.

“Well, as far as we know, only one of us is a killer,” she said cheerfully as she climbed into my car. My frozen expression made her laugh.

At a midnight café booth, she pulled a series of fifteen- to twenty-inch crocheted creatures from her duffel bag—a garish orange lobster-like monster, several deep-sea fish, and a lizard—all made during her prison sentence.

I had first heard about her from a criminal defense attorney and had written to her in prison before she got out. Later, she found me on Facebook. We began meeting regularly in Salt Lake City until she decamped for southern Utah, after which we stayed in touch.

Over six years, I spoke with several of her children, domestic violence advocates, law enforcement officers, attorneys, artists, and formerly incarcerated women who had done time with her. I visited her land three times, twice staying overnight.

Through it all, she showed immense reserves of energy, determination, and physical strength. Despite—or perhaps because of—trauma dating back to childhood, she was buoyed by a boundless love for animals and a wry, gallows humor that usually, though not always, carried her through dark times.

As the years went on, Alden’s bone-deep exhaustion and poor health became increasingly apparent. I worried about her dying out on her land and no one finding her for months.

“Are you at the point where you can’t continue?” I asked five years into our conversations. Her answer underscored how, despite all our time together, I had failed to understand her situation.

“There’s no place else for me to be,” she said.

A visit to the pawn shop

A 2023 Utah Senate bill mandated that law enforcement agencies be trained in the Lethality Assessment Protocol—a tool for first responders to assess the risk of injury or death facing domestic violence survivors.

Two decades earlier, when Alden met Sessions—who had served prison time for drug offenses—such initiatives did not exist, at least not in rural Utah. The couple lived in a double-wide trailer on the outskirts of Delta, a small town in Millard County, with two of her five children and numerous farm animals. Local media coverage of the initial court proceedings, along with Alden’s recollections, paint a disturbing portrait of the events running up to the killing.

“Are you at the point where you can’t continue?” I asked five years into our conversations. Her answer underscored how, despite all our time together, I had failed to understand her situation.

Alden considered local police to be “good ole boys” who did not take her complaints seriously. In 2005, Sessions took a plea deal on a domestic violence and assault charge involving Alden. He was ordered to attend anger management classes and fined, a penalty Alden had to pay since he was unemployed. Despite her repeated phone calls and visits from deputies, her reports of Sessions’ escalating substance abuse, threats, intimidation, animal torture, and abuse went nowhere.

In tears, Alden told me how Sessions killed baby rabbits in front of her, comparing their helplessness to her children. When it became clear the police would not protect them, she decided she had no choice but to do it herself. She bought a .38 Smith & Wesson at an out-of-town pawn shop.

During another of Session’s alcohol and drug-fueled rampages, Alden hid in the laundry room. When he went to hit her, she shot him, and he went down face-first. At some point, she shot him again to make sure he was dead.

Afterward, all she could think to do was to get him out of the trailer. She tied a lariat around his body, attached it to her Jeep, and dragged him out. In the quiet of the early morning, she called the police to confess.

The newly elected local prosecutor wanted to pursue the death penalty. Senior high-profile prosecutors from the Utah Attorney General’s office stepped in and took over the case.

They charged Alden with first-degree murder, obstruction of justice, and desecration of a corpse. Her defense attorney, Jim Slavens—who had represented Sessions on the plea deal—planned a battered spouse syndrome defense. At the preliminary hearing, a female officer testified that Alden blamed Sessions for multiple and intimate injuries across her body.

Afterward, all she could think to do was to get him out of the trailer. She tied a lariat around his body, attached it to her Jeep, and dragged him out. In the quiet of the early morning, she called the police to confess.

“I think today gave kind of a flavor of what occurred on that night,” Slavens told reporters after the hearing.

Almost a year after the shooting, Alden signed a plea deal that was slid under her cell door at three in the morning. So began her life inside.

Not a snowman

In her first years in prison, Alden learned how gender made a difference behind bars. If the men’s prison was an education in brutality, the women’s was one in loss.

“Women tend to have so much anxiety over what they’ll lose next that they rarely fight for anything,” she told me. “Men on the other hand will riot over anything. There’s more incentive to keep them complacent and not doing damage on a large scale. Hence far more opportunities. The women? They just get sad, develop eating disorders and either exist in an over-medicated state or kill themselves.”

Inside, she faced formidable institutional obstacles.

“Creating art in prison is fraught with angst,” she wrote in 2019. She had to fill out endless pages of a “contract” with the prison and wait months until someone signed it. For Alden, her drive to make art was non-negotiable. It was the way she interacted with the world, no matter where she was. Behind bars, she found ways to express herself.

In her first year, eighteen inches of snow on the prison basketball courts offered the perfect large-scale canvas. In her coat, gloves, and orange cap, Alden shoveled snow to build a dragon, recruiting other inmates to scoop up snow with garbage cans. The wings and curled tail stretched out over the court. She used juice from pouches to color the body and wings. There were regulations against building snowmen. But as one prison guard dryly noted, her sculpture was not a snowman.

Her cellmate, Glenna Leavitt, was touched by how Alden beautified their surroundings. She painted murals on the walls of the education department, as well as a quote from Marilyn Monroe: “Sometimes things have to fall apart for good things to come together.”

Another “cellie,” Dana Ufford, said, “There was not a woman in the prison who was not in some way touched by her artwork.”

Crochet was a popular time-killer in prison. For years, Alden dismissed it, but when she dreamed of sculpting a creature through crochet, her subconscious convinced her otherwise. By dawn, she had crocheted a salamander with eyes, toes, and spots.

Her cellmate, Glenna Leavitt, was touched by how Alden beautified their surroundings. She painted murals on the walls of the education department, as well as a quote from Marilyn Monroe: “Sometimes things have to fall apart for good things to come together.”

If buying yarn was challenging—she earned 86 cents a day from prison labor, and the commissary sold yarn for six dollars—coping with the institution’s SWAT team’s incursions into her cell to confiscate her art materials was traumatizing. She estimated she lost 60 percent of her art to guards storming her cell in search of contraband.

“Who needs this much yarn?” snarled one guard, his boot on her neck.

“If you were a woman, you would not have to ask that question,” she had screeched back.

Mortimer/Morticia

Alden left prison in July 2019 wearing stretch black capri pants, flip-flops, and an oversized knit fabric top. Inmates cheered, clapped, and told her she deserved her freedom. Several officers hugged her.

On the outside, she told herself, “I’m going to be bold and do things that aren’t expected of me, or that people won’t consider normal. But I’ll do them anyway.”

She had no illusions about how hard it would be emotionally and psychologically. “The stigma you encounter upon release tends to strengthen the trauma bonds developed in prison,” she said.

Compared with the vast majority of felons, the wealth of opportunities that awaited her upon release was embarrassing. But then Alden was a rarity in the post-prison art scene: not an ex-con who had discovered her artistic ability behind bars, but an already recognized artist. For the next four years she had national and international bookings for art projects with curatorial and academic institutions waiting for her after her release, as well as lectures to present on art and incarceration and women in prison. Many of her invitations came with plane tickets. First up was building a 25-foot-long fish out of repurposed waste through a series of “water creature” workshops she led in New Orleans.

In January 2020, back in Salt Lake City, Alden put her prison-hatched Fish House plan into operation, buying a 44-year-old Dodge mini camper for $600. She would convert it into a mini-Fish House, live in a trailer park in southern Utah near one of her daughters who needed her support, and then set out on her cross-country art trips.

The plan’s flaws quickly became apparent. Not only would the vehicle’s age bar her from being able to establish residency in trailer parks, but the engine never got past 25 mph. So much for cross-country trips.

Alden’s parole officer suggested a trailer park in Leeds, in southwest Utah. It would accommodate the aging vehicle and be close to her daughter.

When she got to Leeds, she decided to raise chickens for eggs. But by then Utah was under pandemic lockdown. The local farmers’ store had no chicks, staff explained. Shoving hordes had cleaned them out of 400 chicks within 10 minutes. Buy them online, they advised.

Discouraged, she started to walk out, only to run into a staff member carrying the sole remaining chick, a Cornish breed typically raised for meat. The staffer was about to dispose of it because, without other companions, solitary chicks usually died.

Alden asked for the chick, and the woman gave it to her.

She did not know the chick’s gender and named it Mort—short for Morticia or Mortimer. With her last $50, she bought 10 chicks online so Mort would have company. It turned out Mort was a hen.

“She was the very first living thing I was allowed to care for and nurture when I got out of prison,” Alden said. “A precious little thing about to be discarded.”

She needed Mort as much as the chick needed her. All her museum and academic contracts, not to mention museum art commissions, were cancelled because of the pandemic. Her bright future as a much-in-demand, formerly incarcerated artist was in tatters. All she had to keep herself afloat were food stamps, sporadic two-digit donations from hen and rooster owners giving her their unwanted animals, and an obsessive need to create.

A home of her own at last

Late one night, scrolling on her phone in search of somewhere to live, Alden stumbled upon a real estate advertisement offering 80 acres in the Escalante desert for a down payment of three thousand dollars, and monthly payments of $250 until she had paid off the total $24,000. The property had multi-purpose agricultural use zoning, so she could keep her dozen or so roosters and hens there. While she had the downpayment from academic speaking engagements and a stimulus check, she did not know how she would pay the monthly $250 on top of car insurance and property taxes. She figured she would cover it by selling her blood, which for several years earned her $400 a month.

She bought the lot, sight unseen.

With the help of a one-time cellmate and several volunteers, Alden moved to the desert on Memorial Day 2022.

They piled her chickens, two hellion-sized Akbash, Turkish mountain guard dogs—Lily and Nemo—she bought for protection as puppies, and her few possessions into a couple of trucks and the old RV. The highway scythed through lush farmland and new housing developments, in some cases home to polygamous Mormon fundamentalist families. The developments gave way to flat lands dotted ominously by trailers abandoned by would-be off-gridders who had run out of luck.

While she had the downpayment from academic speaking engagements and a stimulus check, she did not know how she would pay the monthly $250 on top of car insurance and property taxes. She figured she would cover it by selling her blood, which for several years earned her $400 a month.

She bought the lot, sight unseen.

When they reached the GPS coordinates for Alden’s land, they found the dusty blue-green hues of sagebrush and shimmering pastel mountains. The horn of a mile-long Pacific Union cargo train running along the base of a distant mountain whistled a melancholy welcome. Alden’s glee at so much unadulterated solitude struck her helpers as childlike. But Alden knew her life would change.

Her choice of home seemed willfully blind, and some questioned her sanity. But Wendy Jason, then-executive director of Justice Arts Coalition, which represented Alden, saw parallels with her art.

“It reflects who she strives to be in the world,” she said. “It’s who she wants us to see, someone mystical, deeply connected to the natural world, a healer. It’s her highest self, her best self.”

• • •

That first evening, Alden laid out her sleeping bag and sat on a chair by the fire as Nemo and Lily chased each other in the sand. If she had any doubts about her decision to live out here, what she saw next dispelled them.

As dusk settled, the sky deepened into fierce reds and yellows until the air itself seemed to vibrate with color. Then came the dark—a blackboard of sharp white stars scattered across the sweep of the Milky Way. High above, the lingering trails of jets crossed one another in faint, chalk-white hashtags, a game of noughts and crosses played against infinity. Along the horizon, shades of gray curved with the earth’s edge, as if the world itself were a canvas in the hand of something divine—vast, turning, and alive.

Hunting coyotes

For the first few months of her desert life, Alden pursued “a curmudgeonly, hoboesque existence,” as she described it to the curious. Her shower was a holey bucket attached to a stick. In the summer, she spent time outdoors naked except for boots and an Australian farm hat.

For coyotes, Alden’s dogs had their own solution. Nemo would draw them in with her barking, while Lily circled round behind and tore their throats out. The two blood-drenched dogs would get hold of either end of a coyote corpse and rip it apart.

Alden scavenged construction sites and junkyards for materials to build a frame for a stationary version of the mobile fish house. The skeleton of oval metal bars covered by a tarpaulin was quickly torn apart by the wind.

Early attempts to build a shelter for the animals did not survive the weather either. Again and again, the results of her evolving carpentry skills were wiped out by merciless winds and storms.

Requiem for a dream

Over the next two years, Alden lived in abject poverty, relying on her scavenging skills for materials, food, and water. She slept under six duvets in a decrepit trailer during subzero temperatures. Mice ran over the covers. She worked odd jobs, including manual labor — digging ditches was one of her fortés. When she could get gas money, she visited the food bank in town. Slowly, the edges of her off-grid dream grew darker.

While her building skills improved, the struggles continued. An errant four-by-four hit her on the head, filling her right eye with blood. Debris from the bleed has dogged her vision ever since.

Isolation and lack of reliable transportation made her vulnerable to predatory men. Once, she was stranded for hours with a flat tire. A man stopped to help and then sexually assaulted her. She did not report it: The last person she wanted to talk to was a cop.

She continued selling blood to a local plasma center to cover gas and animal feed. But anemia, exhaustion, and debilitating, severe cramps from the blood draws meant she had to stop. At least she could take a bath at a friend’s house to feel more human.

People promised to help her with building projects, and then ghosted her. Once or twice, she had job interviews for positions that would have been perfect. But each time she arrived, having spent precious money on gas, the potential employer had run a background check and turned her away.

“Men go right into construction if they are in decent physical shape. My age and gender work against me,” she said. “People chalk men’s transgressions up to gender-related stupidity. Almost like they did not know any better. A woman who transgresses is looked upon more as untrustworthy, conniving. Like she has a serious character flaw.”

In July 2022, Alden ran out of money. She had been depending on a university to honor its promise to pay her quickly after she gave a talk on incarceration, but after weeks, there was no check. If she did not get $200 within a couple of days to have water delivered, she and the animals were in deep trouble.

She pleaded for help on an Instagram video, listing the recent disasters. A successful writer sent her two thousand dollars. In a choked voice, Alden posted a second video expressing her gratitude.

Rooster whisperer

Alden’s grip on her dreams seemed only more tenuous, especially when it came to her lack of progress in completing animal shelters or a barn for the chickens.

But then help emerged from two unlikely sources: a builder with a passion for Burning Man and an ex-FBI agent.

She met 42-year-old Nick Tilley through a mutual acquaintance in the backyard chicken community. Raised by a single mother in a rural shack that offered little protection from the chill wind, Tilley was a veteran house builder. But he was most passionate about non-traditional, sustainable housing.

After some unexpected life events knocked him sideways and left him living off-grid in a trailer, he got to know Alden and thought he had found someone he could help. At the same time, he figured Alden could help him.

Tilley’s proposal was to improve Alden’s living situation by building an insulated, water and goat-proof shed where she could work on art to sell to build up an income. Alden’s shed had to be small enough to not require a building permit but still offer sufficient space to work. In exchange, he would build sustainable homes to showcase on her land.

In September 2024, Tilley and a friend put down a foundation and erected the frame of the shed. It was the biggest single milestone of progress in the three years since Alden had moved there.

Weeks later, recently retired FBI agent Jon McPherson came into her life. While conservative, Mormon and a Trump voter, McPherson was not your typical lawman. He cared more about people’s well-being than punishing them.

He had a rooster he wanted to keep, but his wife was terrified of it. Thinking his only option was to put it down, his wife told him, “I’ve got this number for a rooster reserve. Why don’t you call her?”

He met Alden at the home of a mutual friend. She grabbed McPherson’s highly agitated bird, held it gently, talked to it, and caressed its neck. It immediately calmed down. McPherson was smitten. Alden reminded him of an aunt he adored who had a menagerie of abandoned and injured animals.

He had a rooster he wanted to keep, but his wife was terrified of it. Thinking his only option was to put it down, his wife told him, “I’ve got this number for a rooster reserve. Why don’t you call her?”

Alden’s Last Chance Ranch seemed like a junkyard to McPherson. He canvassed his friends and church community for volunteers to help Alden fix it up, but many questioned her mental health.

“It doesn’t make sense to a lot of people that she would feed her chickens before she fed herself and that she would drive 50 miles to pick up a rooster but not have gas to heat a space for sleeping,” he said.

Such perspectives frustrated Alden. “They’re the only companions I have that I can count on, OK? They don’t lie to me,” she said.

McPherson’s family members donated money to outfit a 1970s trailer, refurbishing and caulking it and getting the heat working. Now she had somewhere else to survive the elements and to work. Overnight, it seemed she had leapfrogged from clinging to her land by her fingernails to truly claiming it as her own.

That was not the only good news. A Utah arts official had asked her to speak in March 2025 at Utah Valley University in Orem at an exhibition of state-owned art, including her Fish House. After almost 20 years in the cultural wilderness, the local arts community wanted to hear her story.

When Alden saw the Fish House on display, she could not believe how big it was. She ran her hands over it, adjusting things that were tweaked out of shape or bent. Someone told her not to touch it.

She shrugged. “I made it, I’m gonna touch it.”

Won’t you be my neighbor?

Alden’s platonic relationship with Tilley continued to evolve. In May, they went to a weekend desert gathering for people interested in building their way into new lives off-grid. He wanted to show her similar models to the kind of sustainable homes he planned to showcase on the front of her property.

Tilley had long been unhappy with where he was staying, and over time, they discussed him moving onto her land. Alden was not sure how she felt about having a neighbor. This question came at a time when there were other surprising developments. She started receiving monthly federal checks for supplemental security income, reserved for people with disabilities or little, if any, income. At the same time, a couple who owned 40 acres of neighboring land offered to sell to her. The title included water rights.

With 120 acres and an acre-foot of water, she could legally put up two houses. She agreed to buy it.

“It’s super-exciting and will change everything out here,” she said.

In early June, Tilley moved to Alden’s land. He camped around the property to see where he would put his trailer. While he told her she was inspirational, he struggled with not being able to run his rice cooker and microwave.

“He’s more the ‘glamping’ sort,” she told me.

At the end of the month, Tilley brought his trailer out. “That sure puts a new level of real on things,” she said.

A forever home

By early July 2025, what had become known as the Forsyth fire was 47 percent contained. When the wind blew in Alden’s direction, the basin could still fill with smoke, but she felt less vulnerable than when it had driven her to abandon the ranch. And with Tilley as her neighbor, she knew that there would be somebody who could help.

One night, she could hear the pounding bass of Tilley’s music. He invited her over.

She walked over under a star-dusted cosmos. They sat by a fire and talked. He took out a UV light, and they looked for scorpions. Nemo padded over along with one of Alden’s newer adoptees, a waddling bulldog called Octavia. The dogs slumped down between them.

It would be an evening unlike any Alden had had before. One of shared vulnerabilities and of genuine, matched curiosity regarding each other’s ideas.

They shared ideas to improve life in the basin, talked about past relationships and life experiences. Tilley shared how coming out to Alden’s land was equal parts terror and excitement. It was so harsh, the climate so unforgiving, that being prepared for any eventuality was an absolute necessity.

They saw the land through similar eyes.

“I love it out here,” he told her. “I don’t even wanna leave when I have to go back into town.”

They agreed that it would be a great place for people to decompress, an educational healing sanctuary. Tilley had ideas for special gardens and LED night lights, plans that excited Alden.

Alden’s priorities remained her farm animals. “I’m more into saving animals than people,” she told him.

But she also felt drawn to sharing the therapeutic landscape and healing power of self-expression through art with domestic violence survivors, plans she had first pitched to the parole board and to her family while in prison.

It would be an evening unlike any Alden had had before. One of shared vulnerabilities and of genuine, matched curiosity regarding each other’s ideas.

By 1:30 a.m., for all the laughter and excitement, Alden felt exhausted and ready for bed. She walked back under the light of an enormous moon, the dogs silently following.

Life after prison often felt like one step forward, four back. In the desert years, what made her life meaningful was trying to make conditions better for her animals. While the world struggled with wars, political, economic, and social chaos, she was grateful for qualified solitude.

Above her, the Big Dipper brought back childhood memories of being taught to navigate her way by the seven stars. That night, it served as a reminder that after a lifetime of searching, she had found her home. Shooting stars blazed their finite paths above her in celebration.

“Evil can find you no matter where you’re at,” she said. “For the time being, this is my little safe spot and I’m just trying to share it with a few critters and a few people. Hopefully it will be enough until whatever happens next or wherever I go after this.”