Discovering Mexican Literature of the United States

Reading Chicano narrative of yesterday and today.

December 5, 2016

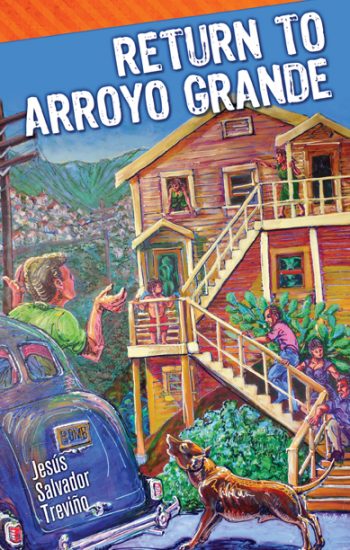

…y No se lo Tragó la Tierra/ …And the Earth Did Not Devour Him; Return to Arroyo Grande

The considerable debt in attention and engagement that we Mexican readers and critics owe to Mexican American and Chicano literature is greatly overdue. Even the most well-read of us have little knowledge of a great tradition that includes everything from precursors, like María Amparo Ruiz de Burton and Américo Paredes, and legends like Rudolfo Anaya, Alurista and Gloria Anzaldúa, to a vibrant community of very active writers: Santiago Vaquera-Vázquez, Stephanie Elizondo Griest and Lucha Corpi. Neglected by Mexico’s heavy-handed official cultural nationalism, Chicano and Mexican-American literature has thrived historically in a double-bind, ignored in the country of origin of the forefathers of its great writers, and simultaneously marginalized in the United States, where Chicanos continue to fight an arduous struggle for cultural recognition. This is a problem even in academic circles, where Spanish programs rarely engage it, given that many of its foundational texts are written in English, and most English departments fail to represent it in its research and teaching, even when it is an important part of American literature. But recognizing this cultural tradition is part of a much larger debt that the society of both countries owe our Chicano and Mexican American brothers and sisters. In a time when the Republican President-elect speaks of mass deportation and a border wall, when many Chicanos and Mexican Americans are denied full legal and cultural citizenship in the United States, and when Mexico fails to provide even basic solidarity to the community, Chicano literature provides a timely and urgent archive of stories, affects, memories and experiences.

I begin this review with the remarks above, because as I read and comment on two great books—Tomás Rivera’s landmark masterpiece …y No se lo Tragó la Tierra (1971) and Jesús Salvador Treviño’s extraordinary new collection Return to Arroyo Grande (2015)–I cannot but feel my own limits as a specialist in Mexican literature who has rarely had the opportunity to engage with the Chicano canon. My reading cannot therefore be that of the specialist, but it is rather an approximation to works that offer a glimpse into a rich world that is both familiar and alien, a territory that I must be bound to explore in full, but of which I know only its most recognizable landmarks. The first thing to note is that the press that brings us these two titles, Arte Público, is an institution to which we owe in large part the existence of a considerable canon of Latino and Hispanic literature. Thanks to the tireless work of Nicolas Kanellos, its founder and director, and to initiatives like the amazing “Recovering the U.S. Hispanic Literary Heritage” Project, those of us seeking to make up the gaps in our readings have a canon accessible and readily available. Given that so many institutions of higher education in the United States, including my own, lack specialists on U.S. Latino and Hispanic culture in general, and Chicano and Mexican American culture in particular, Arte Público is maintaining the archives that will allow for this production to get its due consideration once the American university system fulfills its duties towards the culture of groups that will constitute a quarter of the U. S. population within the next five to ten years.

To read …y No se lo Tragó la Tierra in a new paperback edition is a reminder not only of its great richness and intensity, but also of the continued relevance of the story it tells. Its fragmentary nature remains one of the best literary formulations of our imperfect knowledge of the lives of Latino farm workers …

It is nearly impossible to say anything new about …y No se lo Tragó la Tierra. Originally written in Spanish, and translated into English by Evangelina Vigil-Piñón under the title … and the Earth Did Not Devour Him, the novel is an intensely harrowing collection of fragments and vignettes, that, mostly focused on a young male protagonist and without an established chronology, narrate the experience of migrant farm workers in the 1950s. One should note that Vigil-Piñón’s is not the original translation: the first editions carried a version by Herminio Ríos entitled …And the Earth Did Not Part. …y No se lo Tragó la Tierra manages to configure its narrative using elements of folk Christian religiosity, a rich use of vernacular Spanish and a remarkable economy of short chapters and phrases, something that stands in stark contrast with the recourses to the epic and to magical realism that other Latino and Latin American works of the period favored. In a brutal and concise style that resembles other narratives of rural marginalization, such as the novels of the great Brazilian sertâo writers and Mariano Azuela’s Mexican Revolution classic Los de abajo, …y No se lo Tragó la Tierra provides readers with a vivid experiential narration that provides affective and political meaning to the everyday violence of the farm worker experience.

In its original publication, the book was a keystone of the Chicano literature revival that flourished alongside the political movements. It was the winner of the first Quinto Sol Award, granted by the Berkeley-based press of the same name, and which provided an invaluable forum for Chicano classics to emerge (the second winner was Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless me, Ultima, another indispensable work). It was adapted into cinema in 1995 by Severo Pérez, in itself an unheralded classic of American film. The bilingual nature of the book in all of its U.S. editions performs the double bind I described above. Even though as a Mexican reader I can see resemblances to the aforementioned Mariano Azuela and to the great Juan Rulfo, it is safe to say that there is no canonical literature written in Latin America in the early 1970s that resembles Rivera’s book. It is undoubtedly one of the most significant works in the Spanish language of the decade, providing a formally daring counterpoint—based on silence, violence, brevity and and an intense tension between spirituality and rationality—to the sprawling, totalizing works that became the hallmark of Latin American literature in those years. In its English translation, it also stands as a counterpoint to hallmark works of the time. The protagonist’s experience and the language used to narrate it speak of a much different literary tradition than the one represented, in the very same year of 1971, by the verbal inventiveness of John Updike’s Rabbit Redux or the existential cynicism of Charles Bukowski’s Post Office. Although the novel remains a constant object of reading and scholarly criticism, a full consideration of its formal innovations regarding both Mexican and American literature remains very much a task for the future.

In its original publication, the book was a keystone of the Chicano literature revival that flourished alongside the political movements. It was the winner of the first Quinto Sol Award, granted by the Berkeley-based press of the same name, and which provided an invaluable forum for Chicano classics to emerge (the second winner was Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless me, Ultima, another indispensable work). It was adapted into cinema in 1995 by Severo Pérez, in itself an unheralded classic of American film. The bilingual nature of the book in all of its U.S. editions performs the double bind I described above. Even though as a Mexican reader I can see resemblances to the aforementioned Mariano Azuela and to the great Juan Rulfo, it is safe to say that there is no canonical literature written in Latin America in the early 1970s that resembles Rivera’s book. It is undoubtedly one of the most significant works in the Spanish language of the decade, providing a formally daring counterpoint—based on silence, violence, brevity and and an intense tension between spirituality and rationality—to the sprawling, totalizing works that became the hallmark of Latin American literature in those years. In its English translation, it also stands as a counterpoint to hallmark works of the time. The protagonist’s experience and the language used to narrate it speak of a much different literary tradition than the one represented, in the very same year of 1971, by the verbal inventiveness of John Updike’s Rabbit Redux or the existential cynicism of Charles Bukowski’s Post Office. Although the novel remains a constant object of reading and scholarly criticism, a full consideration of its formal innovations regarding both Mexican and American literature remains very much a task for the future.

To read …y No se lo Tragó la Tierra in a new paperback edition is a reminder not only of its great richness and intensity, but also of the continued relevance of the story it tells. Its fragmentary nature remains one of the best literary formulations of our imperfect knowledge of the lives of Latino farm workers, which today comprise not only Mexican migrants but a considerable Central American contingent, exponentially growing as people from countries like Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras flee the astonishing violence that plagues the region. Rivera’s novel could easily be reimagined as the story of a Central American child living those same realities, in a moment where people running away from mara gangs and drug cartels are deported back to their countries and very possibly to their likely death. Part of our compassion gap regarding the most impoverished of Mexican and Central American immigrants (which are denied even the debate that we have regarding Syrian refugees) is the result of something Rivera narrates very well: the disjointed sense we have of their life experience, which we are unable to capture in full, in their complexity. This is as much the case in 2016 as it was in 1971. Rivera’s book reads like a fully contemporary work because the timeliness of his novel does not cease to increase.

The most striking feature in Return to Arroyo Grande is the stories of social mobility it tells. Arroyo Grande is a West Texas town, and the characters that populate the stories are men and women who returned to the town after experiencing diverse journeys. If Rivera’s characters are those Mexican Americans who face the refusal of a full life in the United States, Treviño illustrates another conundrum: the collapse between the demands of community and identity and the possibilities offered by both the United States and Mexico. In these stories we see characters faced with many great opportunities other Mexican Americans can only dream of: the opportunity to attend college, to participate in the art world, to have a career in Hollywood. But the general tone of the narrative is that of discontinuity. Instead of providing us with the kind of stories of formation so typical of immigrant and minority narratives, Treviño uses magical realism and the uncanny to introduce instabilities between the past and the present. In “Lost and Found,” for example, Choo Choo Torres, one of the most memorable figures in the book, searches for missing people in a park in which he works, only to find that, when those people reappear, they are different than before. The story captures the sense of persecution and uncertainty of the post-9/11 world, showing the absurdity of the surveillance state through the supernatural. In another story, police officer Bobby Hernández records a testimony to try to make sense of his encounter with a family, which leaves him on the verge of mental collapse. The narrated world of Return to Arroyo Grande is one where Mexican Americans, even when integrated to life in the United States, never belong in full to their present, and the magical and fantastical exposes the ripples in that reality. To face this sense of existential instability the book sets forward the idea of community and identity as a place to which one can always return. It is no wonder that two of the characters –I will not disclose which to not ruin reading—end up building a pyramid. Return to the Pre-Columbian origins (something to which filmmaker Robert Rodríguez also alluded when the characters of his 2007 grindhouse tribute Planet Terror take refuge from the zombie apocalypse in Mayan ruins) represents a much larger concern: the importance of cultural roots as a referent to make sense of the present of the Chicano community.

The narrated world of Return to Arroyo Grande is one where Mexican Americans, even when integrated to life in the United States, never belong in full to their present, and the magical and fantastical exposes the ripples in that reality. To face this sense of existential instability the book sets forward the idea of community and identity as a place to which one can always return.

Reading Treviño as a Mexican scholar is a peculiar experience. His unapologetic recourse to magical realism stands in stark contrast to the fact that many Latin American writers of today seek to run away as far as they can from it. Yet, in Treviño’s work, magical realism acquires an altogether different sense. Identity politics in Mexico has historically been a tool of the State to create cultural homogeneity and to create legitimacy to a single-party regime that formally ruled the country for 70 years and whose afterlife remains palpable in Mexico’s many contemporary crises. But in the United States, where Mexicans and Mexican Americans remain the target of demonization and spite from the perspective of ideologues that refuse to come to terms with our presence and our contributions to American society, this assertion of identity and roots carries a fundamental political sense. It is only through the deployment of our complex cultural heritage and history that we can begin to make sense of the community that we need in order to face current challenges and rejections. As a filmmaker who documented like no other the Chicano movement, Treviño writes a fiction that remains keenly aware that the mirages of professional success and middle-class respectability do not relieve us from the duties of community, identity, and memory.

I can only conclude this review by stating the need to read more of these works, acknowledging the intellectual hunger that was awaken with this encounter. As someone who professionally represents Mexican culture in academia, I feel a greater sense of duty in knowing this culture and in advocating its visibility, particularly here in the Midwest, where so many Americans, including my own students and colleagues, live in a regrettable state of oblivion regarding this grand legacy. Readers, both American and Mexican, will it is hoped find in themselves their own version of this duty, after reading two authors who have lead the way so boldly and bravely, and who give us the sort of stories that a more democratic and inclusive America and a Mexico that needs to come to become more just with its diaspora need for their future.