How My Art Zings!

Two children's books promote getting inside the world of art.

November 7, 2016

The Fantastic Frame: Danger! Tiger Crossing; My Life in Pictures (Bea Garcia)

We tend to assume that children have a simplistic grasp of art. We feign astonishment at stick figures without necks and smile to ourselves at blotches of color proclaimed to be castles. But in two new books published last spring, art plays an expansive, sophisticated role in the lives of young people, showing them engaging as meaningfully—if not more so—than any grown-up.

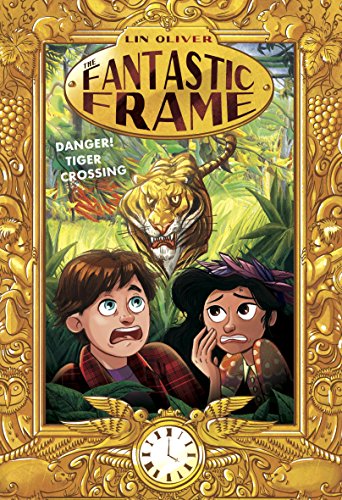

The Fantastic Frame: Danger! Tiger Crossing by Lin Oliver and My Life in Pictures by Deborah Zemke share a common theme: the power of creativity to take us somewhere new. Both books are the first in new series, poised to take readers on a multi-book journey of their own. Despite these overlaps, the books will attract different sorts of readers. While The Fantastic Frame is rooted in art history, it is no textbook lecture. Part fantasy, part white-knuckled adventure, The Fantastic Frame is suited to those who look to reading for their adrenaline rush. My Life in Pictures, on the other hand, is more of a personal exploration, and will appeal to those who consider our inner lives to be adventure enough.

When we meet Tiger Brooks in The Fantastic Frame: Danger! Tiger Crossing, he has just moved into a new apartment. At first, the neighborhood seems typical enough, but things quickly get interesting when he meets his neighbors. There is Luna Lopez, the free-spirited girl who lives upstairs, and next door, an old hermit named Viola Dots and her talking orange pig named Chives.

Naturally, it is the pig that most piques Tiger’s interest. He and Luna decide to investigate, which means entering Viola’s sinister-looking house—something Luna claims no one has done in 50 years. But Chives lets them inside, where they discover dozens of canvases, whose descriptions savvy readers might recognize as Van Gogh’s Starry Night and Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus.

Although Viola is horrified to discover the children in her home, Luna charmingly chatters her way into her confidence. It is then that we discover the mystery that drives this series. Fifty years ago, Viola’s son David disappeared into a painting—one hung within an ornate, gilded frame. At the same time, Chives was spit out, severed from the painting he once inhabited. David’s rescue now falls to Tiger and Luna, who are transported into whatever painting is held within the frame’s gilded edges.

In this first book, the two tweens are transported into the windswept, rain-soaked jungle of Henri Rousseau’s Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!). Here, the illustrations turn from black-and-white to full color, suggesting how dull our world would be without art. Although the pair is dazzled to find themselves in a painting, they quickly realize that the work’s eponymous feline—crouched in anticipation and eyes blazing—is alarmingly alive. Driven by fear, the pair flees through the forest, swimming across a river and hiding in a cave, the tiger’s hot breath and flashing claws never too far behind.

Although we are generally trained to focus on the aesthetic qualities of visual art—what brushstroke is used? Is it realistic or not? Is there perspective?—Fantastic Frame tacitly and masterfully explores instead the emotional life of a painting rather than its appearance.

At its most basic level, the story is pure adventure, and can be enjoyed as such. But for the more insightful reader, it shows that art itself can be an adventure. Granted, we might never actually be sucked into a canvas. But with a little imagination, we can easily insert ourselves into the world depicted. Although we are generally trained to focus on the aesthetic qualities of visual art—what brushstroke is used? Is it realistic or not? Is there perspective?—Fantastic Frame tacitly and masterfully explores instead the emotional life of a painting rather than its appearance. What must it feel like to be next to that tiger? What is the tiger itself capable of? What does its life as a jungle hunter entail? It introduces an entirely fresh way of considering art, one that every museum educator likely strives to achieve. By doing so, it offers subtle guidance on how we too might allow ourselves to be transported by a painting.

The book also includes back matter about Tiger in a Tropical Storm (Surprised!) and about Rousseau himself. In a country where art history is, at the earliest, taught at the high school AP level (and even then, only rarely), this series will prove invaluable for getting children excited about art, teaching them about notable paintings and artists, and showing them the life of a painting beyond its mere appearance.

While Fantastic Frame revolves around the impact of an artist’s work, My Life in Pictures taps another side of creativity: our own. Like many young girls, Beatrice Holmes Garcia keeps a diary to chronicle the moods and events of her days. However, rather than narrate her journal entries through words, Bea draws hers out with pictures—her book is meant to be her diary itself. She is careful to tell us when her illustrations depict a real event, and when they portray a situation that she merely wishes would happen, creating a seamless world between life’s daily occurrences and the rhythms of her own internal universe.

While Fantastic Frame revolves around the impact of an artist’s work, My Life in Pictures taps another side of creativity: our own. Like many young girls, Beatrice Holmes Garcia keeps a diary to chronicle the moods and events of her days. However, rather than narrate her journal entries through words, Bea draws hers out with pictures—her book is meant to be her diary itself. She is careful to tell us when her illustrations depict a real event, and when they portray a situation that she merely wishes would happen, creating a seamless world between life’s daily occurrences and the rhythms of her own internal universe.

But her drawings also reveal her insecurities and fears. We suffer through her despair when her best friend and neighbor Yvonne moves to Australia, and feel her isolation when she tells us she is friendless. She illustrates her wrath for Bert, the monstrous boy who moves into Yvonne’s house, and her flushed anger when he teases her at school. During a geography lesson on the second day of school, she takes her revenge through—what else?—her drawings. As Mrs. Grogan teaches the class about Earth’s extremes, Bea draws Bert in a shark cage 36,000 feet below the Pacific Ocean, teetering on the tip of Mount Everest, and whirling through the highest winds ever recorded.

While Fantastic Frame revolves around the impact of an artist’s work, My Life in Pictures taps another side of creativity: our own.

She becomes so engrossed in her vindictive drawings that Mrs. Grogan, growing wise, snatches her diary. It is every student’s worst nightmare. Later, she heartlessly singles Bea out to name the highest point on Earth. As Bea begins to panic, she suddenly visualizes her illustration of Bert on Mount Everest. Through this visual aid, she is able to tell her teacher not only the name of the mountain, but its precise height, no doubt delighting proponents of arts-integrated curricula.

Unfortunately, that small miracle cannot divert the coming disaster, when Mrs. Grogan begins to show the class Bea’s drawings of Bert. There he is, in the shark cage 36,000 feet below the Pacific Ocean, teetering on the tip of Mount Everest, and whirling through the highest winds ever recorded. The drawings are met with uproarious laughter and cheers for Bert. Bea simply hides beneath her desk.

But as it turns out, Mrs. Grogan’s goal is not to mock or punish, but to praise. She refers to Bea’s pencil as “a magic pencil that just took us all on a journey of discovery,” just as Rousseau’s paintbrush proved similarly magical in The Fantastic Frame. The pencil, says Mrs. Grogan, “belongs to one Amazing Artist.”

Just as Bea’s artwork has taken her classmates around the world, experiencing natural extremes without actual danger, the act of drawing transported Bea into a zone of creativity, oblivious to her actual surroundings. Although these journeys are not as literal as Tiger’s and Luna’s, the message is the same: art is capable of leading us to new, sometimes surprising destinations.

And no place is more surprising for Bea than the world of popularity. With her new reputation as an amazing artist, she suddenly has friends to play with on the playground, and to sit with at lunch. Even Judith Einstein, the smartest girl in class, compliments her drawings, when just that morning she acted like she had never seen Bea before in her life. It seems as though drawing is capable not only of depicting her dream of having hundreds of best friends at the same time, but of also fulfilling it.

Whether this sudden popularity is a result of Bea’s newfound artistic caché or her newfound confidence does not really matter. What is clear is that art has given Bea a sense of identity and self-confidence, which can be hard to come by at any age, but perhaps especially during childhood and adolescence. Art can empower us, it seems, long after our pencil leaves the paper.

It is anyone’s guess whether these books will inspire readers to pick up a pencil and create a new world, or visit a museum and enter an artist’s universe. At the very least, they will plant a seed in readers of the power and possibility of art, and with any luck, will inspire them to pick up the next book in the series.