The Improbable Museum of Winston Churchill

January 29, 2026

I did not know of an institution named America’s National Churchill Museum, in the central Missouri countryside, until a friend asked if I would like to drive out to have a look last week. Or maybe I had heard of it but shuffled the information to whatever part of the brain holds seeming incongruities. Finding a museum dedicated entirely to Churchill, in Fulton, Missouri, two hours west of St. Louis, seems as odd as it would be to find a Charles de Gaulle museum in Brooklyn (the one in lower Alabama), just north of Rome (in Alabama’s Conecuh National Forest).

The museum, well worth a visit, is on the grounds of Westminster College, a private liberal arts college with 600 students. The basis for the museum is that Churchill, accompanied by President Harry Truman, a native Missourian, made his famous post-war speech “Sinews of Peace” there on March 5, 1946. (“The name ‘Westminster’ is somehow familiar to me. I seem to have heard of it before,” Churchill teased.)

The speech is more popularly known as the “Iron Curtain” speech, because Churchill warned that a year after WWII had ended, “an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe…and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in many cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow. […] The Communist parties, which were very small in all these Eastern States of Europe, have been raised to pre-eminence and power far beyond their numbers and are seeking everywhere to obtain totalitarian control. Police governments are prevailing in nearly every case….”

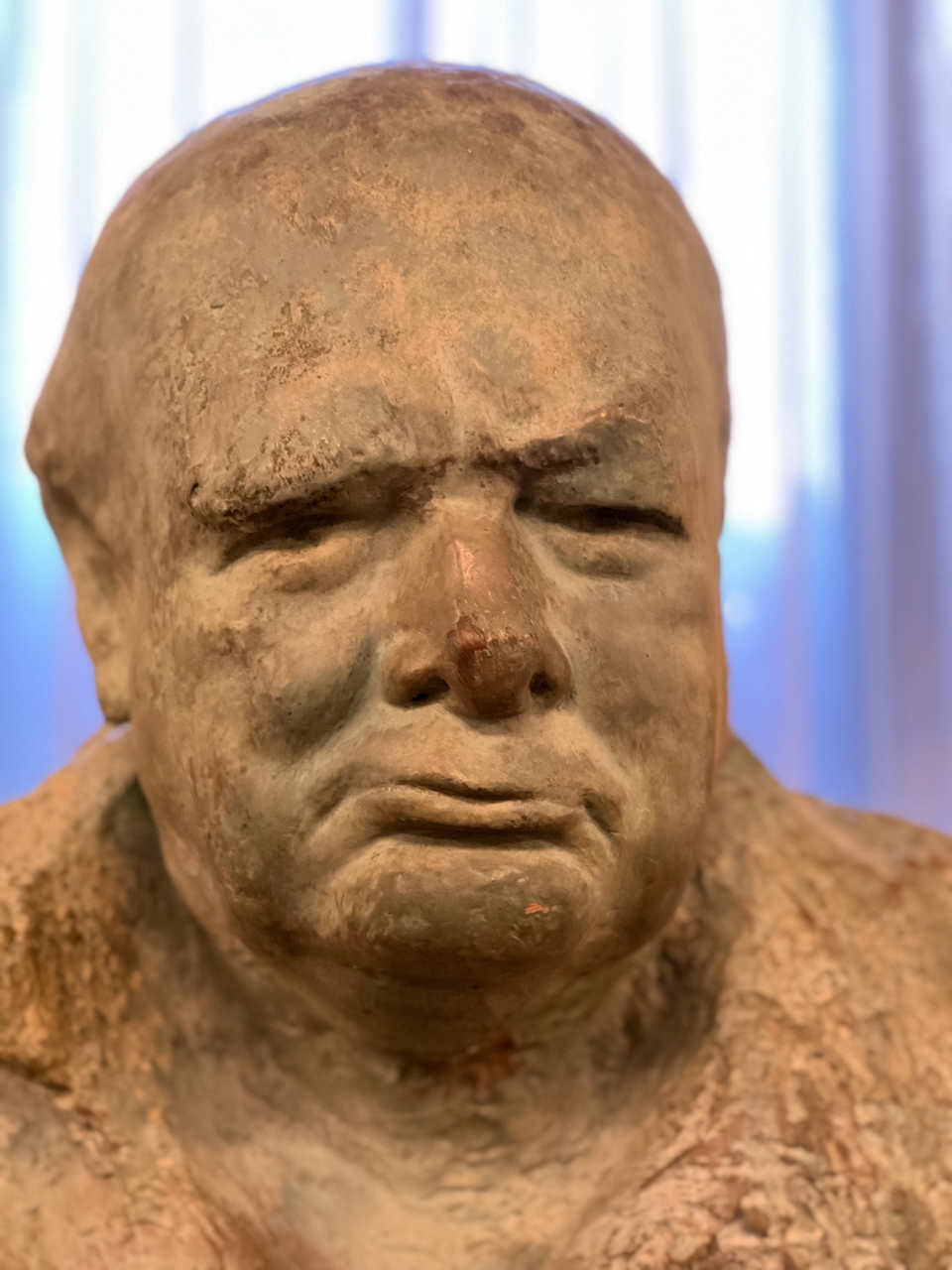

The museum contains many bronzes and other art (including two of Churchill’s own paintings), a miniature of Blenheim Palace and a recreation of Churchill’s office, displays of WWI memorabilia, contemporary political cartoons, photos, a small theater showing a documentary film, and of course lots of labels (signage) with explanations.

Astonishing to me is the stone church sitting on top of the museum: the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Aldermanbury, London, founded in about 1200. Shakespeare is said to have “lived about one block from the church for much of his London residency and may have occasionally worshipped at St. Mary’s,” and John Milton’s second wife, Katherine Woodcock, “was a member of the parish at the time of their wedding,” curatorial labels say.

The church was already some 450 years old when it burned in the Great Fire of London (1666). It was rebuilt by Christopher Wren and then was burned again in a Nazi firebombing in 1940. The longer story of its history, salvation, and restoration in Missouri is fascinating. It was shipped for free to the States in 1965, as 650 tons of ballast, in U.S. Shipping Board ships. The London Times called the restoration on Westminster’s campus, completed in 1969, “perhaps the biggest jigsaw puzzle in the history of architecture.” The church serves as the home chapel for the “Eagle Squadrons” of the Royal Air Force, 244 Americans who flew to protect Britain, from 1940, before the United States had entered the war, until 1942, when the squadrons were absorbed into the US 8th Air Force. Labels in the museum says one-third of the men died in the war.

The museum does a particularly good job humanizing Churchill, especially regarding his struggle to find his career as a young man, his army service, and his defeats and reversals as a politician. (He appeared at Westminster a year after losing the election for Prime Minister in 1945.) The museum tries to place all this in the context of half a century of incredible change and violence but does not deal much in current understandings of Churchill’s ideas of imperialism and his racial views.

It would be unrealistic, too, to expect museum labels—about the Cold War, the fall of the Soviet Union, glasnost, détente with Russia, and especially US/UK/EU/NATO cooperation, which are portrayed as “solutions to the issues [Churchill] framed in the shape of our contemporary world”—to reflect the large changes in the West, driven by American policy chaos, over just the last year.

Retired four-star admiral William H. McRaven (a former commander of US Special Operations Command, which worked closely in his time with counterparts around the world), published an op-ed in The Atlantic two days ago, after President Trump had denigrated NATO allies.

“Winston Churchill once said that ‘there is only one thing worse than fighting with allies, and that is fighting without them,’” McRaven writes. “If we continue to show disdain for our allies, if we fail to appreciate their contribution to our national security and greater global stability, we may find ourselves fighting alone someday. And trust me, war is never a contest you want to fight alone.”