How Amazon’s Catalogue Triggers Our Collective Memory

By Ben Fulton

October 26, 2024

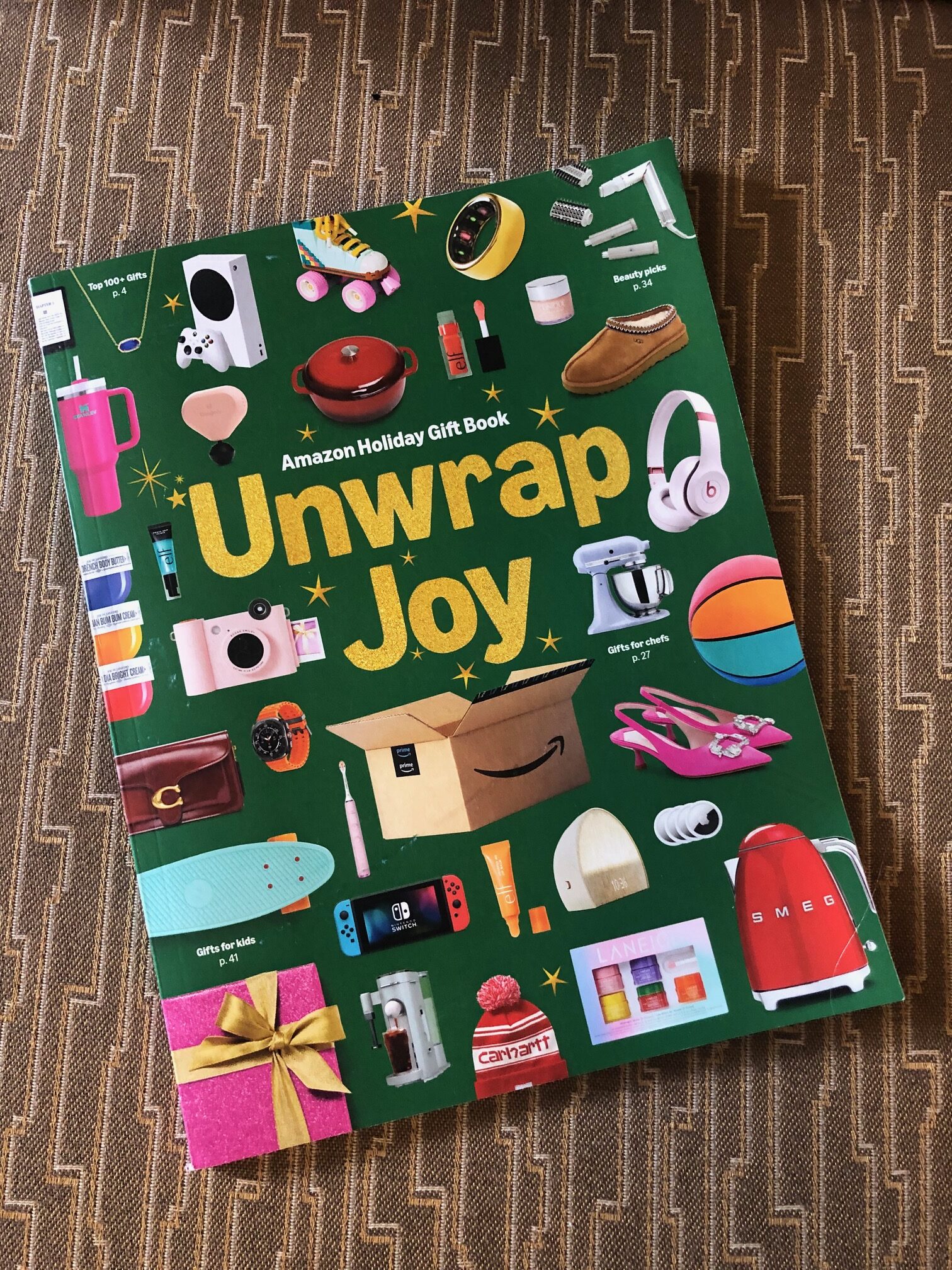

If you are one of more than 200 million Amazon Prime members worldwide, you probably have sitting on your kitchen table what has sat on mine for the past week or so: the Amazon Holiday Gift Book, Unwrap Joy, printed in robust paper stock.

If you did not receive your copy, there is of course no reason for despair. So long as your home internet service is current and your browser is updated, amazon.com will always be there, ready at a moment’s notice to take your order and your money.

The legions who received a copy, however, might well have scratched our heads in disbelief. Truth be told, I scratched my noggin several times prior to asking why the world’s biggest retailer, aka “The Everything Store,” would even bother.

The answer resides deep in the rhetoric of marketing, a language that the United States basically developed in the wake of England’s Industrial Revolution, and that is now spoken worldwide. The short answer is that, like vinyl LPs, analog culture has invaded the margins of all things digital in order to treat us all to a bit of nostalgia. Thumbing through Unwrap Joy, I was flooded by a surge of memories involving print catalogues of seasons past. The length of my reminiscences was vast, including the Sears catalogues of my grandparents’ basement, the newsletter listings from Midnight Records in New York City, and especially—most especially—the J. Crew catalogues that dropped into my many apartment mailboxes as regular as rain.

Yes, anyone who has ever circled in pen, on catalogue paper, the product of their heart’s desire is almost certainly of “advanced age,” however defined these days. But as a card-carrying member of Generation X , I found it intriguing to learn that today’s modern marketers value the print medium in ways they most certainly did not a mere five or so years ago. The “print experience,” it is said, is less shredding of the nerves than staring at your screen. From a business perspective, print catalogues distributed in tandem with emails have the potential to increase sales by as much as 24 percent. This makes complete sense. Who wants to be reminded of work, where we stare into glowing screens ad nauseum, when what we really want is to relax and shop?

In certain circles, print catalogues have become collector’s items. An eBay search reveals that the rarest—such as the spring 1990 issue showcasing model Linda Evangelista in pre-famous leisure wear—can fetch up to $250 per copy. Unearth a super-rare copy of J. Crew’s 1998 catalogue featuring the Dawson’s Creek cast and you could sell it for a cool $500. Catalogues are the official record of our material desires, the truest archive of fashion and its cultural changes. Find an old catalogue listing clothes, hardware, or even candles. Flip through it, fingertips smudged with colored ink as your eyes dart from item to price and back again. Short of reading a Dickens or Tolstoy novel, this simple act is the closest most of us will ever get to time travel, and in far less time than a master novelist would demand.

Unwrap Joy has its moments. The “Customers’ Most-Loved,” page 12, lists everything from a retro toaster to Vanlinker retro sunglasses to tempt the nascent consumer touring its pages. What the list refuses to offer is prices. For that we must scan QR codes at the bottom corner of each page. For a shopper of advanced age such as myself, this step interrupts the warm ethos of the old-style catalogue “experience” just enough to soil it ever so slightly.

If the print comeback of the catalogue wants to work in tandem with the pushy, even hostile, experience of Amazon’s online behemoth, and the multitude of marketing emails, we should hope future catalogues will develop more helpful features, or just tell us what these friggin’ items cost while the impulse to buy is fresh.

Then again, since when did the urge to shop in this country ever need more help? The urge we need, and that we crave in secret, is the long pause over quiet memories that only an old catalogue can bring. That is not to say anyone should spring for the $250 necessary to buy a vintage J. Crew catalogue online, but if that is what solace costs, so be it.