“You can be an outlaw and be anything you want”: A Memory of Lester Bowie

By Chris King

October 11, 2024

Long before Jazz St. Louis was a mainstream arts organization in a branded arts district with its own performance space named after some of our most important local philanthropists, it was a phantom of the heart. It felt more like some scrappy club than a not-for-profit corporation.

When I was introduced to this scrappy little jazz club, its music director was a quirky human named Joanne Collins, who had an uncanny sense of connecting with the world’s greatest living jazz artists. I never was privy to the organization’s finances, but I sensed that Joanne had a way of offering to pay jazz artists what they were worth, then coming through with that hefty guarantee, come hell or low ticket sales.

When I fell into Joanne’s orbit, I was a graduate student teaching writing at Washington University, a traveling indie rock musician, and a freelance journalist with a passion for jazz but no deep knowledge of the form. I suspect Joanne liked me because she was running a shoestring arts organization with more commitment to paying jazz artists properly than to paying, say, writers or bartenders, and I worked cheap.

I worked cheap for Joanne on a Jazz St. Louis jazz train trip to Chicago. I hope the image of a jazz train to Chicago makes my point about the scrappiness—this was an extended family of friends and scenesters taking over a train car and some hotel rooms on a journey into Jazz Chicago, not some slick travel package.

Though I would later write newsletters for Jazz St. Louis that gave me an opportunity to sit down with people like the great St. Louis pianist John Hicks (1942-2006) and get paid a few pennies to develop a better understanding of this beautiful music, my heyday with Jazz St. Louis was definitely that jazz train to Chicago and, most providentially, my service as its staff bartender.

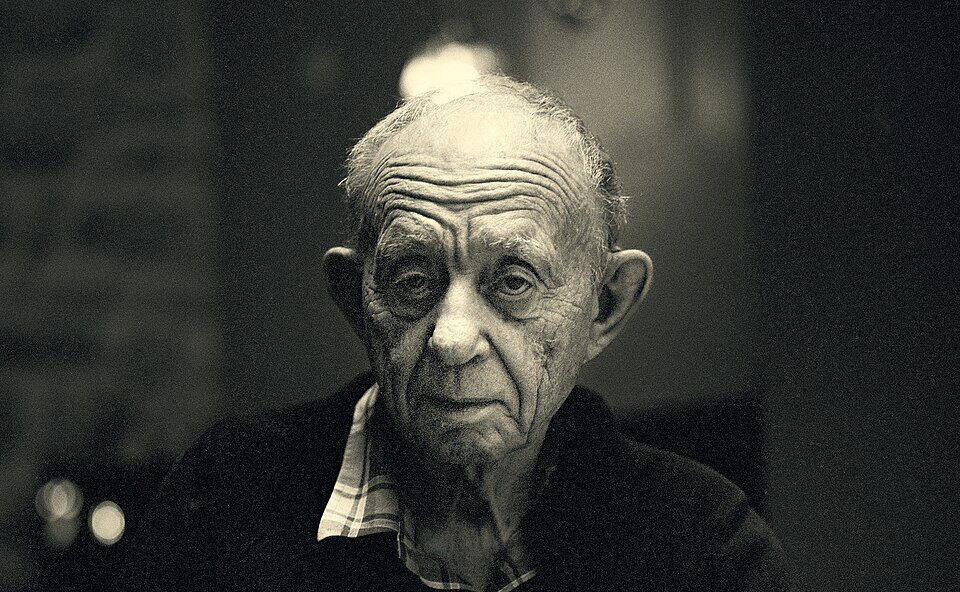

Throughout the weekend, there was always a bar, whether on the train or at a venue or in the hotel, and it was my responsibility to stand behind that makeshift bar and serve drinks to the jazz faithful. This probably would not have been memorable had our private guide to Jazz Chicago not been the legendary St. Louis trumpet player, bandleader and composer Lester Bowie (1941-1999). For that is how I came to stand next to Lester Bowie for the better part of a weekend in Chicago.

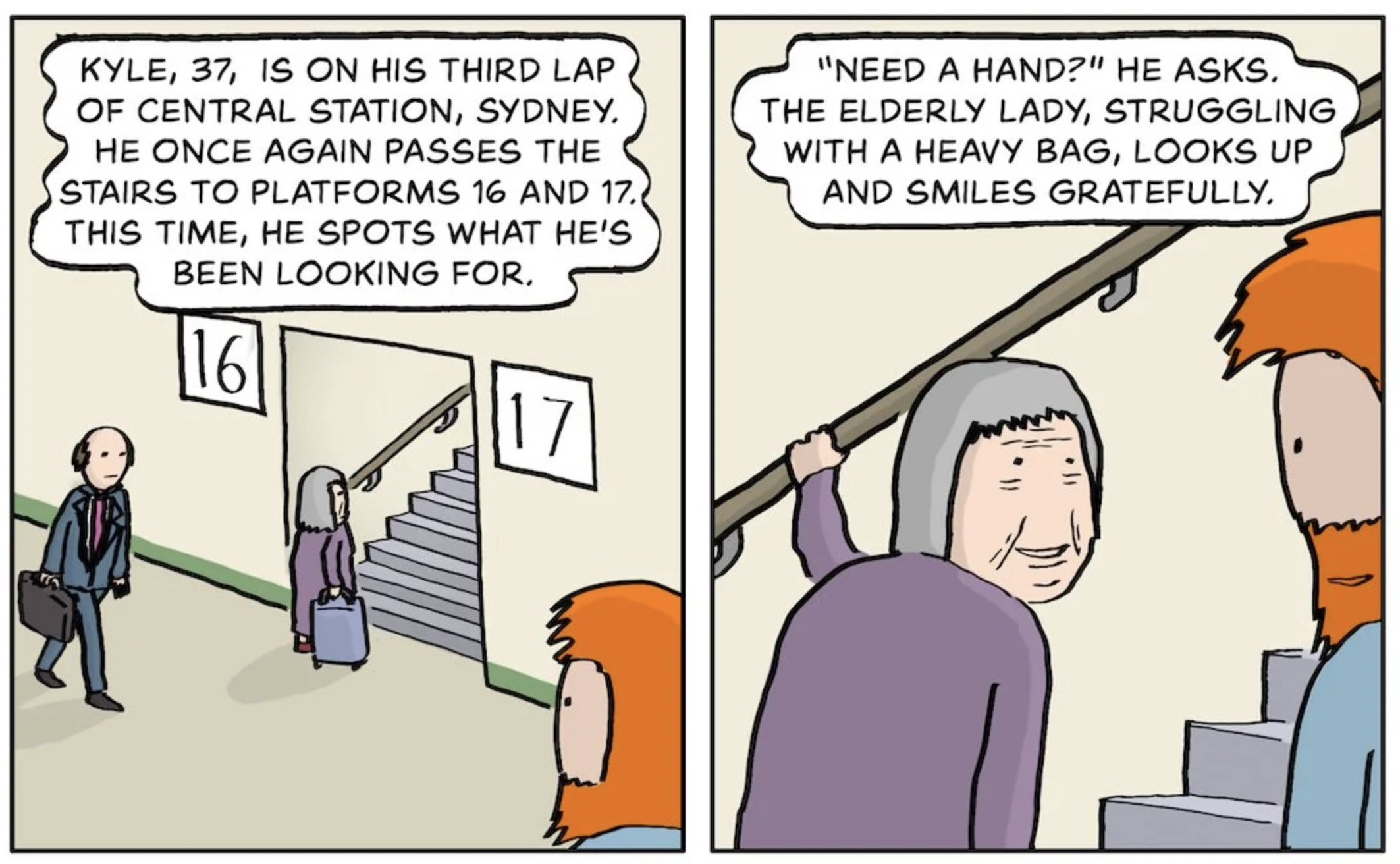

My impressionistic journeys into jazz had thrown me into many of Lester’s musical worlds. I loved Lester Bowie’s Brass Fantasy with its playful reconstructions of pop and soul classics. On the other side of the Lester spectrum was the conscious chaos of Art Ensemble of Chicago. Lester led a smoking funky organ band. Joanne was over the moon for The Leaders, where Lester was one of many band leaders who played together. Lester’s often goofy solo work (he paid homage to both Howdy Doody and the immortal Daffy Duck) inspired me as the leader of a quirky rock band named Enormous Richard that used humor onstage (we put out bowling pins costumed after the guys in the band) and in our songs (cf. “Dogs with Their Heads Out the Window”).

Lester clearly had a genuine connection with Joanne, and as her man Friday, I started out on a good footing with him. I must have told Lester about our many mutual friends spurring from my deep collegial friendship with Eugene B. Redmond, East St. Louis poet laureate and praise singer of Lester Bowie, Hammiet Bluiett, Oliver Lake, and all the creative forces associated with the Black Artist Group. BAG took its template from the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians that Lester cofounded in Chicago after he left St. Louis. Through Redmond I knew many of Lester’s home crew, and I must have told Lester about all that when I found myself standing beside him behind the bar.

Of course, I did not flatter myself that Lester Bowie gravitated toward me throughout the weekend because we knew some of the same cool people. Rather, the bar provided a temporary shield from all the Jazz St. Louis faithful who wanted a piece of him, and I was the guy stationed behind that shield serving drinks.

I happened to be so agitated internally at that precise moment, a major decision was so immediately upon me, and I had no one else behind the bar to talk to other than Lester Bowie, that I started telling this great man my problems.

You see, I was at a crossroads in my life. I was a successful graduate student in English at Washington University who was being given signals that if I kept doing what I was doing I could become a professor of English literature, which seemed like a humane and interesting way to become a grown-up. I was halfway through my 20s and had spent those formative years reading and writing about English literature just enough to keep my teaching scholarship but really more preoccupied with writing songs and playing rock music on the road with my friends.

Suddenly, I had a decision to make. Our band had just come off a two-week East Coast tour, where the singer of a band with a budding national reputation, King Missile, had seen us perform at CBGB, the incubator of punk rock in New York. The band’s leader John S. Hall liked what he saw and knew we were a Midwestern band with a following in many cities where his band had never played. He told me he wanted us to open as many shows on King Missile’s national tour as made sense.

Just before the jazz train pulled out for Chicago, King Missile’s manager called to give me the dates for their upcoming national tour, which coincided almost day for day with my next semester of teaching. I was not going to be able to do both. Starting this next semester, I was going to be either a traveling musician or a college professor. I was mulling over that imminent decision that entire Jazz St. Louis weekend in Chicago.

I tried to talk to Joanne about it, but she was temperamentally a little flighty—a better listener to jazz music than to other people’s personal problems—and she had a jazz train itinerary to honcho. That was why I found myself standing behind a series of makeshift bars in Chicago talking about my problems to the only other person within earshot, which was the legendary Lester Bowie.

At one point Lester finally looked at me and said, “So, do you want to be a rock musician, or do you want to be a college professor? You can be an outlaw and be a rock musician. You can be an outlaw and be a college professor. You can be an outlaw and be anything you want to be.”

Now I hear this statement as a gnomic kind of Buddhist koan: something meant to guide the seeker to define his own truth rather than to offer explicit advice. However, at that moment, what Lester said to me had the same consequence as if he had grabbed me by both shoulders, stared deep into my eyes, and said: “Dude, you’re a rock musician, not a college professor.”

When I got back to St. Louis, I called King Missile’s manager and made our band available for every date on their upcoming tour. I told my dissertation advisor that I was leaving graduate school and would not be teaching for them the next semester. That was how Lester Bowie changed my life, and I have felt oddly close to him ever since. When Lester died of liver cancer some seven years after that Jazz Train to Chicago, on November 8, 1999, at the tragically young age of 58, it did not seem real, and of all the people I have known who are dead, Lester is the one person whose death I never accepted in my bones.

Two codas to this story. One is a story of mundane music industry treachery. The other is a story about the ghost of the afterlife that lives on even in those of us who profess not to believe.

King Missile’s manager went on to book us for most of their band’s national tour. It turns out that is the kind of information, once solidified, that gets reported to the industry, and that was how I learned that the vultures of the music industry pore over trade publications trying to figure out who is eating their lunch and whose lunch can they devour. Who was this unknown, unsigned band Enormous Richard, and why were they opening on a national tour for a new buzz band out of New York with a video, “Detachable Penis,” trending on MTV?

First I got a call from King Missile’s manager letting me know we would not be playing the San Francisco date after all. He said the iconic promoter Bill Graham’s organization still ran the San Francisco scene, Graham had a nephew in a band called Rights of the Accused that wanted to open the San Francisco show, and King Missile was not in a place to go up against Bill Graham’s people just yet. This call would be repeated many times regarding many markets where Bill Graham’s nephew wanted to eat our lunch.

Then calls started coming in from the other direction. Calls started coming in from club owners who had done good business with our band and liked us and was not going to be pushed around by Bill Graham’s nephew. Calls came from Lawrence, Kansas; Columbia, Missouri; Columbus, Ohio; of course, our hometown of St. Louis; and one of Lester Bowie’s adopted cities, Chicago, telling me some boring band they did not know with Bill Graham’s nephew in it was trying to horn in on our King Missile gig, but they were standing by us.

When the dust settled, we had no more nor less gigs spread out over that next semester than if John S. Hall had never seen us play at CBGB and never asked us to be King Missile’s opening act. I had not needed to drop out of graduate school or quit my teaching scholarship to do all of the gigs with King Missile that we were finally offered. I guess Lester Bowie had tried to tell me: You can be an outlaw and be a college professor.

Lester Bowie had been dead for thirteen years when his former wife and musical partner the great soul singer Fontella Bass (1940-2012) died in St. Louis. I unfortunately never met Fontella, though I knew many people who did know and love her. At the time of her death, I was managing editor of The St. Louis American, St. Louis’s historic Black newspaper (you can be an outlaw and be a newspaper editor), which gave me an enviable friend-of-the-family connection to many events in St. Louis’s Black community. For those reasons, I went to Fontella’s funeral.

I also went because she had been Lester Bowie’s girl. I thought in some weird way I should be there for my guy Lester.

Fontella’s funeral started with a jazz procession led by two of St. Louis’s most beloved jazz artists, the Bosman Twins. I sat on the edge of my seat, electrified by the vibrant joy of the Bosman Twins dancing into this beautiful funeral ceremony blowing their saxophones. I was also possessed by a very strange feeling.

I knew Lester Bowie had been dead for a long time, and I think I know that dead people do not get up and dance at the funerals of people they have loved. But I never could escape an eerie feeling. I felt that Lester would twirl into the sanctuary behind the Bosman Twins, his signature white coat flowing open, waving his shining trumpet and finally blowing it with the voices of edgy angels. To this day I would have to say I still am not entirely certain that I did not see Lester Bowie dancing into Fontella Bass’ funeral ceremony behind the Bosman Twins, seriously clowning around with death.

October 11 was the 83rd anniversary of Lester Bowie’s birth. November 8 will mark the 25th anniversary of his death.