Making Merry Adventure from Sophisticated French History

Graham Robb pens a quirky, rich, and startling different history of France.

October 20, 2023

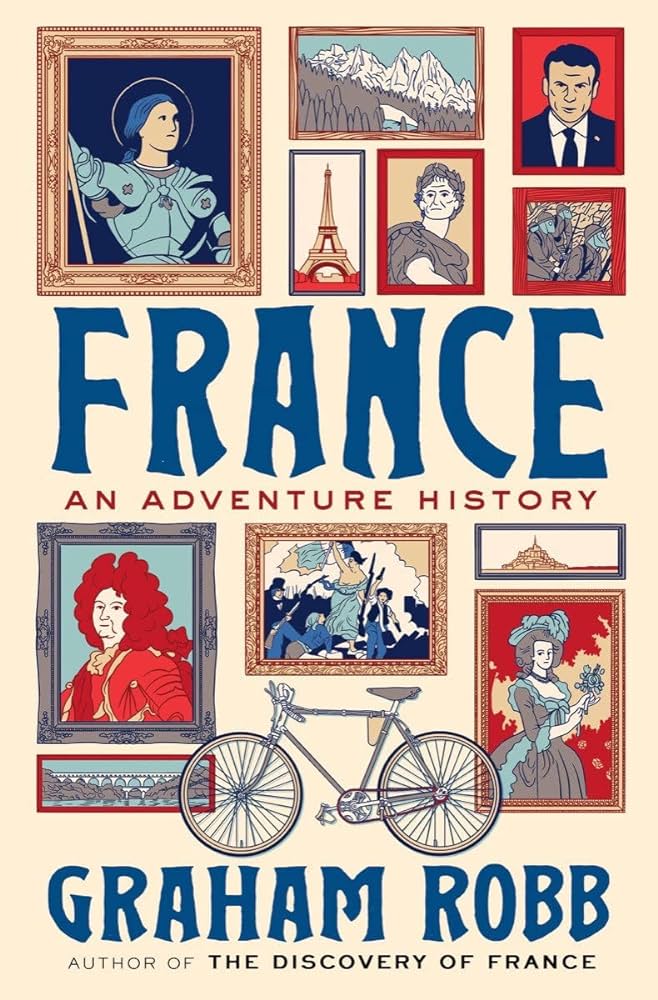

France: An Adventure History

The dust-jacket of Graham Robb’s France: An Adventure History reproduces several images suggestive of the long history of France, from Julius Caesar to Emmanuel Macron. Joan of Arc and Louis XIV are there, along with Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People and the Eiffel Tower. But the two most revealing images are actually a bicycle and an Alpine forest because Robb has written such a distinctive history that his bicycle and the vegetation of France are as important as the kings and generals are.

Robb warns his readers, in a short opening section entitled “About This Book,” that his history will be different. He and his wife, Margaret, had spent years in “gentle cycling for weeks on end” (2) around provincial France, leading him to develop his critique of those histories of France which “never strayed beyond the outer boulevards of Paris, except when driven out by war.” (3) As Robb explored the terra invisa of France, he became convinced of an important flaw in general histories: “Physical geography was often absent, left to some other dimension or discipline.” (2-3)

Robb has written such a distinctive history that his bicycle and the vegetation of France are as important as the kings and generals are.

This does mean that Robb’s book lacks a grounding in archival research and the obscure periodicals of provincial libraries. He provides fifty pages of references to document this backbone to his writing. Nor does the love of cycling and physical geography mean that Robb’s work is short of erudition. His strength in French (two of his previous books were written in French)1 often combines with an old-fashioned strength in Latin, quoting Virgil as fluidly at the beginning as Hugo at the end. Nonetheless, the man on the bicycle saddle cannot resist occasionally teasing “indoor historians” (47) and reminding them that “All of the Parisian sites mentioned in this chapter can be visited on a bicycle in less time than it takes to find a parking space.” (401)

Robb’s “adventure” approach to the past is dominant from the start of France: An Adventure History. His first six chapters cover French history “From Ancient Gaul to the Renaissance” and half of those chapters have titles celebrating trees and shrubs. The book opens in 57 BCE with Julius Caesar beginning a bloody campaign in Gaul which would kill a million of Rome’s neighbors. In the opening sentence, Caesar shares attention with the shrubbery: “A tall man with piercing black eyes was staring at an impenetrable hedge.” (9) The chapter ends with the observation that “Since the Gauls rarely built in stones, these living hedges are practically the only Gaulish structures to have survived for two thousand years.” (20)

Robb uses Caesar’s De Bello Gallico to teach us how “The Hedge” (which is the title of this chapter) could nullify the advantage of the Roman cavalry (which could not attack through it) or impede a phalanx formation of Roman infantry. It is a fascinating lesson in physical geography even for former Latin students. Fortunately, Robb also vigorously reports that Caesar vanquished the Gaulish terrain, and overcame hedge and forest to impose a terrible genocide (he uses this word) on the Nervii (the warrior peoples who once dominated Gallia Belgica). It is not a traditional account of Caesar’s rivalry with Pompey or his strategic options against the Gauls, but it is a fascinating chapter.

Part One repeatedly returns to this theme, teaching us about the physical geography of provincial France. A chapter on Brittany after the fall of the Roman Empire is a lesson in why it was finis terrae (subsequently Finistère). It was an “Invisible Land of the Woods and the Sea” (41-55), not conquered until the late fifteenth century and not annexed by France until 1532. Robb dodges “flotillas” (45) of local saints and even the purported Merlin the Enchanter, whose tomb was still drawing prayers on slips of paper when he visited it in 2006. For those who think that Merlin belongs to British history, Robb provides a map (one of many excellent maps) of the Frankish Empire in 843 (after the division of Charlemagne’s empire among his sons). Brittany is identified as “Britannia Minor.” (405)

All of the basic elements of Louis XIV’s reign are present, but not in the narrative format students might expect. They are blended with relief from a textbook style through moments of eye-brow-raising detail.

Robb’s chapter on Louis XIV shows how he can combine physical geography with the usual suspects of French early modern history. He covers the political reign of Cardinal Mazarin while the king was young; the aristocratic rebellion of the Fronde, during which Louis’s cousin, the Prince de Condé ruled much of France; the revocation of Henri IV’s Edict of Nantes and the subsequent war on French Protestants, leading to a Huguenot diaspora spreading from South Carolina to South Africa, while other Calvinists retreated into a life in the “desert” near the Cévennes mountains of the south; the catastrophe of domestic war (“A third of all children between the ages of one and nineteen perished.”) (125); the expansion of the French colonial empire into a “New France” (including over one million square miles in North America); the taming of rebellious nobles, taming them from hunting dogs into lap dogs, with their home provinces bullied by royal intendants.

All of these basic elements of Louis XIV’s reign are present, but not in the narrative format students might expect. They are blended with relief from a textbook style through moments of eye-brow-raising detail. We also meet “the infantivorous Beast of the Gâinais … a long-legged she-wolf the size of a horse.” (121) Then it is the young king’s “amorous training with Cardinal Mazarin’s seven specially imported Italian nieces.” (131) (The king’s sister-in-law reported that he was “not fussy” about conquests provided by the church.) (132) And, of course, we get glimpses of seventeenth-century medicine, ranging from Louis’s favorite decoction of opium and rose petals (“He had never taken anything so pleasant.”) (133) to his regular enemas.

That would probably make a sufficient chapter for most historians, but Graham Robb’s devotion to physical geography means this chapter does not revolve around slaughtered Protestants or royal recreation with the Mazarinettes. As the chapter’s title (“A Walk in the Garden”) suggests, Robb is especially interested in Versailles, more the Grand Canal than the Hall of Mirrors. After the king was shocked by seeing a more-royal-than-the-king’s palace (Nicolas Fouquet’s spectacular Vaux-le-Vicomte), Louis XIV devoted much of his life to surpassing his minister’s residence. Fouquet was imprisoned and the great artists who had created Vaux (the architect Louis Le Vau, the painter and designer Charles Le Brun, and the landscape gardener André Le Nôtre) were taken by the king to build him something greater. Soon they were creating an entirely new landscape outside Paris, leveling villages, and removing everything from churches to worshippers. The plan for a “Petit Parc” of a modest four thousand acres soon grew to a domain seven times as large as Paris was. Robb shows us the king, without hat or wig, walking his emerging gardens, as fountains, grottos, and a Royal Kitchen Garden emerge from mud and muck. Versailles remained a construction site for the rest of Louis’s life, and he personally wrote a walking guide to a basic three-mile hiking introduction. Ten thousand workers, many of them conscripted peasants, died (from disease and accident) in creating these royal wonders. And from the day Louis moved his court to Versailles until the day the angry women of Paris dragged Louis XVI back to a palace and a prison in Paris, the wondrous new physical geography would be a royal residence for barely a century.

Robb introduces his interests into every chapter. Sometimes a bicycle only makes a brief guest appearance, as when he uses a troublesome bike on a train to illustrate the pre-World War One French concept of revanche (revenge). And then, near the end of the volume, he devotes a full chapter to the Tour de France. “Any bicycle owner,” he points out, “could…ride on the same roads.” (333) Thus, he wraps the history of the Tour, founded in 1903 by a sporting magazine, around the virtual participation of Margaret and himself, cycling near the peloton. The Tour de France, Robb argues, “democratized and dignified” unknown villages in provincial France, as the cyclists passed through. Previously, these “anonymous locations” might only become known after a battle, a crime, or the witnessing of a miracle. Now they might see a baroudeur (“someone who fights a hopeless battle for honour’s sake”) (347) or become one of the “holy sites of cycling”2 when some tragedy led to a monument “like a home-made Station of the Cross.” (343) They might even see Graham and Margaret whisk across a finish line ahead of the pack (as happened at the Tour du Doubs in 2011). But just when the chapter might seem an unusually self-indulgent idiosyncrasy, Robb turns the subject into an analysis of French society and asks us to think about different perspectives. In the 2003 Tour, eight of the top ten finishers are known to have cheated (performance-enhancing drugs). Until 2020, “no French-born rider of African or Asian parentage had ridden in the Tour.” (346) And why were there few Black faces in the crowds?

France: An Adventure History remains, from cover to cover, a truly different history. It is long and densely packed with knowledge, just not told in a traditional narrative. The chapter on World War One should catch the attention of American readers who are probably well-versed in the story of the battles of the Marne and Verdun, but may never have heard of the battle of Rossignol on August 22, 1914, at the very start of the war. In barely twelve hours of fighting on that day, more than 27,000 Frenchmen (including colonial infantry) were killed, about half the number of Americans killed in the 16 years between 1959 and 1975 in Vietnam. French soldiers died at a rate of two men every three seconds. (Later in the “Great War,” the British would surpass this carnage at the battle of the Somme.) Robb’s view of the fighting would not be complete, of course, without a discussion of the physical geography of the Ardennes forest, not so far from the Hedge which slowed down Caesar in 57 BCE but not the German panzers of 1940.

The Tour de France, Robb argues, “democratized and dignified” unknown villages in provincial France, as the cyclists passed through. Previously, these “anonymous locations” might only become known after a battle, a crime, or the witnessing of a miracle.

Reviewers have been favorably puzzled about how to describe Robb’s mixture. The reviewer for The Spectator (Philip Hensher) called this book “ceaselessly interesting” (March 12, 2022), and that is definitely true. The reviewer for The Times (Ruth Scurr) enjoyed Caesar’s Hedge and Napoleon’s flowerbeds and dubbed the book “a quirky chronicle” (March 5, 2022), and that is also true. Others have said “winningly eccentric” and idiosyncratic (see above). After all, this is an author who one day saw “a giant tree” depicted on an ecclesiastic map of 1624, and soon set off on another bicycle adventure to find “The Tree at the Centre of France.” (Chapter 6, 95-115) This reviewer is glad that Robb did not choose a map with sea monsters because Robb is surely one of the most original historians of France writing today.

1 Robb is an exceptionally prolific author. He began his career writing on modern French literature, producing studies of Balzac, Hugo, Rimbaud, and Mallarmé. He extended that work with two volumes in French on Baudelaire. His interest in French history began with two previous volumes, The Discovery of France and Parisians: An Adventure History of Paris. His interest in the natural world has also led to three volumes. A twelfth volume considered Homosexual Love in the Nineteenth Century.

2 Robb reports several such monuments which he found during his travels. For example, a plaque “on a peaceful stretch of tree-lined road in the Tarn” is quoted in full: “Here, on 14 July 1968, Raymond Poulidor, having been run over by a motorbike, lost all hope of winning the Tour de France.” (345)