The Arrival of Asian American Culture

A new book reminds us of the rich complexity of Asia America.

September 21, 2023

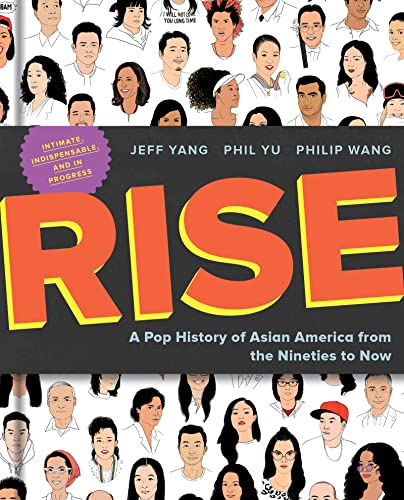

RISE: A Pop History of Asian America from the Nineties to Now

Leveraging their unique insights as cultural critics and producers, Jeff Yang, Phil Yu, and Philip Wang track the evolution of Asian American representation to narrate how a collective Asian American identity and culture was forged over the past thirty years. The timing of the book’s writing and release critically shapes its objectives. Coming into 2020, the Asian American community experienced both greater mainstream visibility and acceptance with the release of blockbuster films like Crazy Rich Asians (2018), as well as the sudden halt in creative production and rise of anti-Asian racism with the onset of COVID-19. The authors were soberingly reminded of “how quickly successes can be erased and progress can disappear,” thereby fueling a commitment to “show the work—to make sure that the steps that moved us forward were preserved.” (vii) As part of this endeavor, they not only celebrate exceptional and headline-worthy moments of popular recognition, but also the oft-overlooked contributions of unsung heroes whose steadfast labor and sacrifice made such breakthroughs possible. The culmination of these efforts is a sweeping historical account of Asian American identity and community formation that is at once nostalgic, rooted in the present, and critically forward-looking.

Phil Yu notes: “The history of Asians in Hollywood has largely been scrawled in invisible ink.” Since the era of the silent film, Asian American representation was largely limited to fleeting portrayals of yellow peril, model minority, or perpetual foreigner caricatures.

RISE is organized around key historical junctures of Asian American racialization, visibility, mobilization, and representation. As a “pop history of Asian America,” the book skillfully strikes a balance between education and entertainment and is made accessible to both academic and popular audiences of various ages. While taking a long view of the Asian American experience, the text centers on periods following the enactment of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, when “the first wave of kids born to [Asian] immigrants started to come of age” and explore the question of what it meant to be “Asian American.” (x) The story necessarily begins in the late sixties when members of the Asian American Political Alliance coined “Asian-American” as a panethnic social and political category that, arguably for the first time, organized distinct groups of Asians in the United States under a common racial umbrella. From the 1980s to the 2010s, as the authors chart, there have been other critical moments in Asian American history—e.g., the murder of Vincent Chin, the Los Angeles Riots, 9/11, and COVID-19—that compelled later generations to revisit, interrogate, and transform the meaning and scope of this collective identity. Popular culture, however, is the central site of racialization and race-making explored.

Phil Yu notes, “The history of Asians in Hollywood has largely been scrawled in invisible ink.” (140) Since the era of the silent film, Asian American representation was largely limited to fleeting portrayals of yellow peril, model minority, or perpetual foreigner caricatures. More often, Asian American characters and themes were entirely displaced from the silver screen and therefore popular imaginations of U.S. national culture. Over the course of the past three decades, however, Asian American representation on the big screen and other arenas of popular culture has slowly but surely become increasingly visible, nuanced, and self-determined. Growing up, Asian Americans of my and earlier generations would not have been able to anticipate the current quality and breadth of “Asian American media.” It would have been even more difficult to imagine that Asian and Asian American music and food would become “all the craze” and enter the mainstream lexicon. As the authors trace, this dramatic shift was in significant part due to the arrival of high-speed internet and social media.

Starting in the early 2000s, Asian American artists and cultural producers ingeniously took advantage of social media to independently distribute content and tell their own stories. Unencumbered by the racialized strictures of the corporate entertainment industry, platforms like YouTube offered Asian American cultural producers of various stripes—e.g., musicians, actors, comedians, lifestyle vloggers—a “stage, a screen, a space to perform where once there’d been nowhere else to go.” (301) Speaking for myself, it was shortly after finishing college in 2009 that I first encountered Just Kidding Films, Wong Fu Productions, and Timothy DeLaGhetto, among other trailblazers of “Asian American YouTube.” Witnessing their hilarious skits and vlogs, I realized it was the first time that I really had access to a (modest) range of public media that was distinctively Asian American, critical, grounded, and recognizable. I had until then rarely, if ever, witnessed Asian Americans “on screen” discussing issues of anti-Asian racism, stereotyping, hyphenated identity, and intergenerational conflicts. Given that this content was created by and for Asian Americans, I felt I had newfound access to a safe space to untangle and make light of the complexities and contradictions of my racialized experiences. Reviewing comments and responses from other Asian American viewers, I knew many similarly felt seen, connected, and hopeful.

As the authors emphasize, in addition to greater and more multifaceted racial representation, social media provided young Asian Americans a digital space to find fellowship. With the rise of platforms like Twitter and Instagram, other Asian American content creators continued to explore their talents and interests as artists, chefs, food critics, motivational speakers, activists, etc. In collaboration with their audiences and other cultural producers, they also advanced a national network of community whose consumption, advocacy, and organizing created an audience for Asian American characters and themes in popular culture. In line with its emphasis on unsung heroes and moments in between major headlines, RISE importantly underscores these underlying forces as being pivotal to building the visibility and demand that generated the recent burst of Asian American breakthroughs in mainstream television and movies. The collective momentum culminated in what is popularly known as “Asian August” in 2018, with the success of films like Crazy Rich Asians and To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before promising to usher in “a new era for Asian Americans on screen.” (430)

The form of the book animates its content’s focus on pop cultural milestones. It unfolds like a family scrapbook of personal reflections, photos, illustrations, comic-book pages, poems, and interviews, bookended by framing essays that contextualize the cultural milieu of a specific period. The writing is at once educational, thoughtful, bold, and humorous, with recurring sections like “Yellowface” brazenly taking hilarious jabs at White-washed Asian characters in Hollywood. For example, regarding Christopher Walken’s portrayal of “Feng” in Balls of Fury (2007), contributor Nancy Wang Yuen states, “No one would think this look was anyone other than Christopher Walken cosplaying as Faux Manchu.” (289) What makes the book especially engaging is its frequent inclusion of interactive graphics, such as a step-by-step guide through Koreatown’s nightlife scene and tour of the typical “Asian Home.” Sections like these animate familiar, yet subtle Asian American cultural traits, like the common practice of keeping a “plastic bag full of other plastic bags” (120), typically stored in the base cabinet under the kitchen sink. Given the continued lack of nuanced portrayals of everyday Asian American life, these pages, like the digital communities made possible by social media, cultivate a familiar and imagined space of communal bonding. They thereby also prompt and invite Asian American readers to imaginatively add to the script based on specific aspects of their personal experiences.

The text’s mixed-media, scrapbook format also prominently features interviews, roundtable conversations, and personal reflections that present readers the rare opportunity to hear directly from various Asian American public figures and pop culture icons. The range of people featured is quite impressive and includes the leads of The Joy Luck Club (1993), the main cast of Better Luck Tomorrow (2002), actress Sandra Oh, comedian Kumail Nanjiani, professional basketball player Jeremy Lin, as well as lawyer and public policy advocate Maya L. Harris. Such sections humanize these figures’ narrative profiles by not only centering their voices, but also by emphasizing the mundane details that shaped their personal and career trajectories. The roundtable discussions with Asian American actors are notably informative and engaging, as they present multiple voices in conversation and provide an intimate, behind-the-scenes look at the creation of some of our favorite pop culture moments. It is especially heartening to witness groups of Asian American artists bonding over common racial experiences and fondly sharing memories of how they were inspired by and found community in each other. For example, in a conversation among a “veteran group of Asian American performers” (430), Dante Basco affectionately shouts out fellow narrator Justin Nguyen and other earlier Asian American actors for offering hope, mentorship, and support at a time when Asians were few and far between in the industry. In another interview with Daniel Dae Kim, Ken Jeong, and Randall Park, Jeong celebrates the success of Fresh Off the Boat (2015-2020) and its principal cast of Asian American actors—which includes Park—for making it even possible for him to have had his own ABC sitcom, Dr. Ken (2015-2017). Like the book as a whole, community remains a central theme in such discussions.

The form of the book animates its content’s focus on pop cultural milestones. It unfolds like a family scrapbook of personal reflections, photos, illustrations, comic-book pages, poems, and interviews, bookended by framing essays that contextualize the cultural milieu of a specific period.

RISE stunningly charts the making and evolution of Asian America over the past several decades. The sheer volume of history, media, and content covered is itself impressive and laudable. The different sections, together, importantly illustrate how the steady arrival of Asian America truly took the cooperative effort of a village. While the emphasis is on collective identity and struggle, through the range of voices included, the book is also critically attentive to the differences that exist between and among Asian groups in the United States, depending on ethnicity, context of emigration, generation, colorism, and intersection of social identities, among other factors. As the contributors suggest, Asian America remains a definitely formed yet provisional community. We are still figuring out “[basic] questions, like, “when we say ‘Asian American,’ who exactly are we talking about?” (185)

As a loving critique, I may say that RISE could be more inclusive of class, regional, and cultural diversity. Like most existing representations of Asian America, its narrative profile arguably remains skewed towards the experiences and sensibilities of upwardly mobile, suburban youth. For people like the young Asian Americans I grew up with in mixed-class, multiracial neighborhoods in the New York Metropolitan Area, the distinctive “Asian American” cultural tastes therefore showcased in sections like “Generasian Gap,” “How to ‘AZN,’” and various “playlists” may not quite be relatable. Nevertheless, it would be unfair to demand a book of such breadth to cover everything. As Jeff Yang states in the “Afterword,” “There was a lot we didn’t get to. And we’ve really only gotten to the beginning of our collective story.” (466) Perhaps, given our recent claim to greater visibility and the fact that RISE is arguably the first volume of its kind—especially as a “pop history of Asian America”—overzealous readers like myself may hastily expect it to be the Asian American story. Upon critical reflection, however, I am humbly reminded of the difficult yet important work of representing a coherently diverse community. I therefore see the “gaps” in the narrative, as well as the authors’ frequent acknowledgment of them, as incentives for us to tell more stories. I also see them as invitations for us to continue to create spaces for further, nuanced discussions of heterogeneity, multiplicity, and intersectionality. To borrow from author Phil Wang, in thirty short years, “we went from ‘take what we can get’ to ‘picky eaters.’ But either way, it’s clear that we’re still hungry.” (314)