Most Timely: Hooray for Hollywood

Black actors protesting Oscar racism is nothing new.

January 26, 2016

After winning Best Actor at the Golden Globes this year, Leonardo DiCaprio gave an acceptance speech that draws on a long Hollywood tradition. After thanking his make-up artists he, lastly, shared “this award with all the First Nations people represented in this film and all the indigenous communities around the world. It is time that we recognize your history. And that we protect your indigenous lands from corporate interests and people who are out there to exploit them. It is time that we heard your voice and protected this planet for future generations.” As this speech demonstrates, film awards do more than reward the best in their field: they represent the stable center of Hollywood’s prestige project and are crucial to cementing the cinema’s status as socially-informed art. The prestige granted by the institutions of the Hollywood Foreign Press and the Motion Picture Academy is critical to the industry’s overall claim of social relevance. Actors like DiCaprio and directors like George Clooney would like to link their films to broader social movements, though in fact Hollywood’s relationship to political struggles has always been decidedly ambiguous.

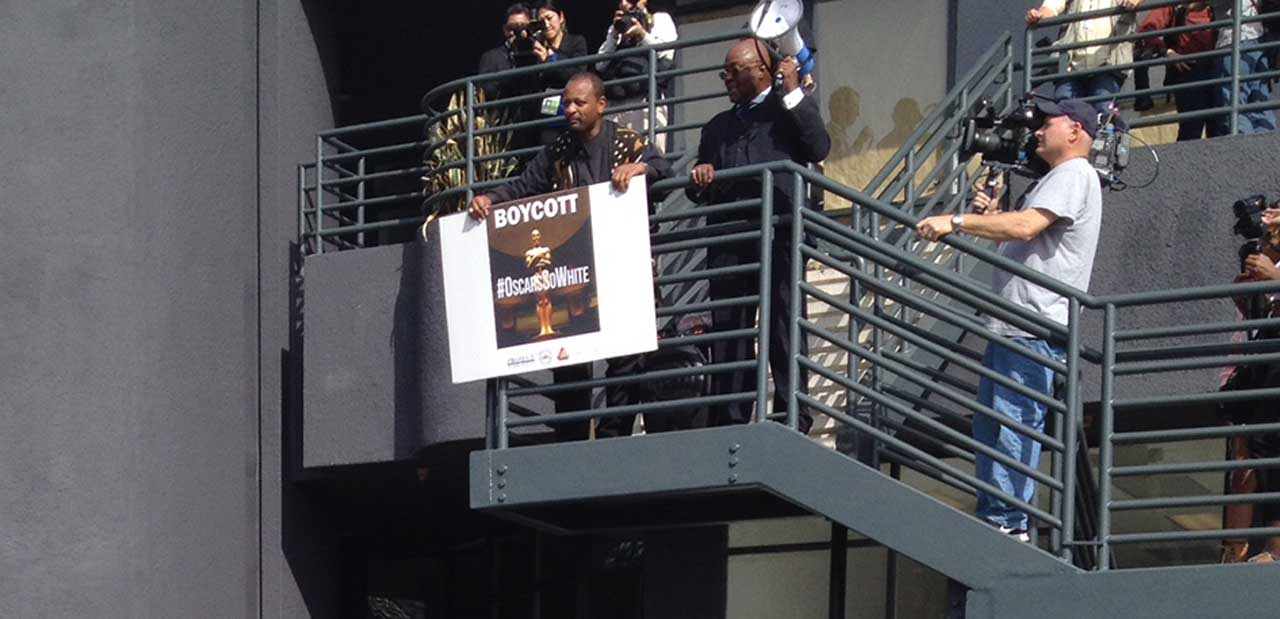

This year’s Oscars protest underscores just this ambiguity. It is encouraging in terms of the nation’s discussion on race and African-American civil rights because black outrage is based not on any individual act of racism but on a nebulous history of inaction, institutional racism, and structural bias in an industry that would like to claim social responsibility. Indeed, it is the very sameness of the award show, and its system of merits, that has struck an activist chord among affected black actors. With the help of social media, this protest has become a part of a broader aggregate and conversation on black life in America. The protest encourages us to read the “non-text” text of the award show against the backdrop of black employment figures and the Black Lives Matter movement (one that has been fueled by Do It Yourself “DIY” images of police encounters emanating from quite the other end of the media spectrum). The significance of this year’s awards protest lies in the strength of the black, social-media borne critique of the whiteness of the Oscars as an extension of a broader black reckoning with the history of white indifference to the significance of black lives and accomplishments. It speaks to the rise of not only a movement but also the possibility of a new black spectatorship, one highly invested in and conscious of the politics and signification of the black image—wherever it is present or conspicuously absent.

Actors like DiCaprio and directors like George Clooney would like to link their films to broader social movements, though in fact Hollywood’s relationship to political struggles has always been decidedly ambiguous. This year’s Oscars protest underscores just this ambiguity.

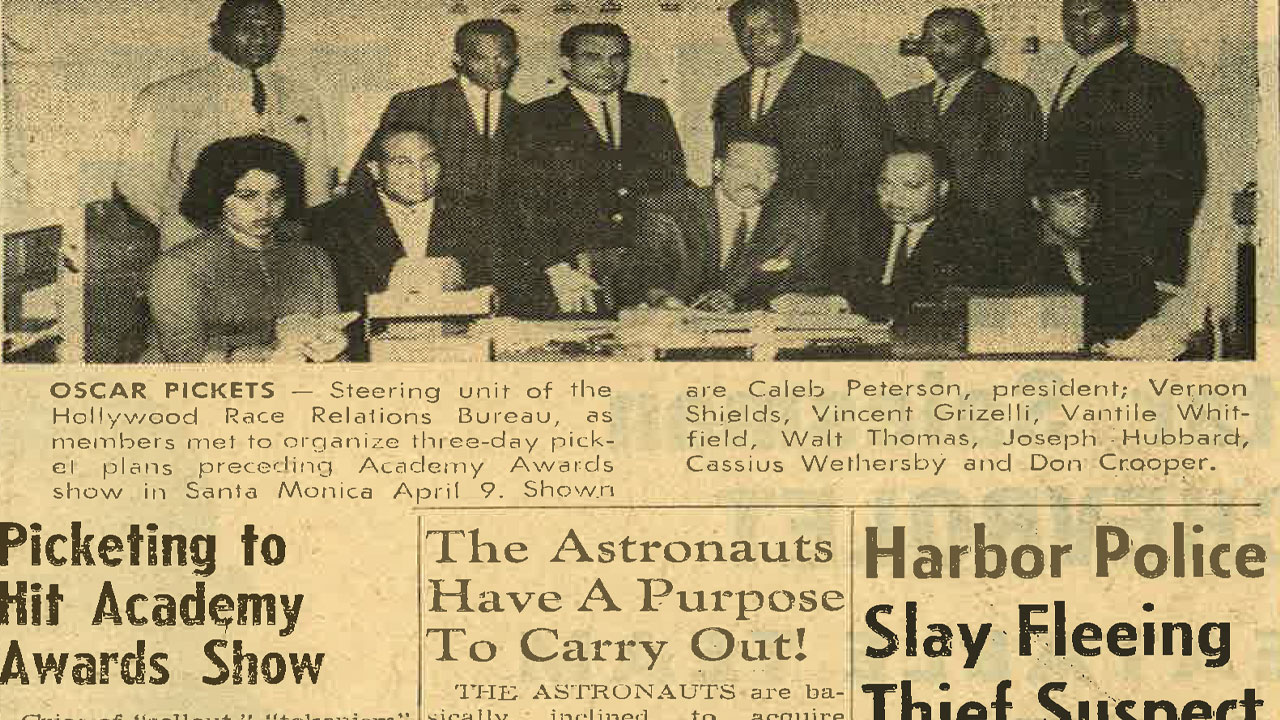

Though this year’s dissent may seem anomalous, it is part of a longer tradition of activism aimed at the Academy Awards. In 1962, while civil rights protests rocked the U.S. South, Caleb Peterson and his organization The Hollywood Race Relations Bureau launched a strike against the racism of the Southern California, picketing the Oscars and publicly claiming the industry presented an “unrealistic” view of African Americans and systematically denied them entry into the field of filmmaking. Peterson was a black Hollywood actor who, after mild successes, felt keenly the limits of Hollywood’s racial glass ceiling. He was a founding leader of the International Film and Radio Guild (a post-WWII pressure group that also granted awards to socially-aware films) and later, in the early 1960s, formed the Hollywood Race Relations Bureau. He came to public attention in the 1930s when he won an oratory competition. A stint in Eddie “Rochester” Anderson’s stage show won him the star’s favor and, with it, an audition at Paramount. But after several significant but painfully brief roles, including a part as a decorated soldier in Stage Door Canteen (1943), and as a discriminated-against black GI in Till the End of Time (1946), his film career did not advance.

Perhaps it is better to see Peterson’s 1960s Race Relations Bureau less as an organization than as a temporary formation born of radical desperation against Hollywood’s intransigence and seeming imperviousness to the rising tide of civil rights. Peterson clashed with the better-organized NAACP, whose Hollywood Branch favored “talks,” negotiation, and the long game over direct action. Peterson’s sensational, flinty campaign included not only picketing the Academy Awards but also downtown L.A. movie houses and eventually also New York film premieres. In picketing The Longest Day’s (1962) token inclusion of only one black soldier, Peterson was joined by the Congress of Racial Equality. The protest eventually won him an audience with Twentieth Century-Fox head of production Darryl F. Zanuck. As the Los Angeles Sentinel noted, the Hollywood Race Relations Bureau was protesting not only “unrealistic” representations but “nebulous” ones. Indeed, the very unformed nature of Hollywood’s black representation seemed an offensive symptom to Peterson.

In the midst of Hollywood buck passing, Peterson and a sizable group of compatriots adopted an egalitarian and unilateral Hollywood strategy that was admirably direct: protest everyone. Peterson recognized that although the Academy was not the institution granting jobs, it was the one defining success.

Several weeks before the Academy Awards show in 1962, Peterson proposed picketing the ceremony, prompting ex-heavyweight champion Joe Louis to state that he would not attend the affair if it meant crossing a picket line. Then-Academy president Wendell Corey countered Peterson by saying that the Academy “only gives awards” and doesn’t make pictures. But Peterson had already begun a picketing campaign aimed at film premieres and Hollywood studios. Though the industry had made some recent hires, Peterson averred it was “token hiring” not an “overall thing”: Peterson wanted deep and abiding changes. In the midst of Hollywood buck passing, Peterson and a sizable group of compatriots adopted an egalitarian and unilateral Hollywood strategy that was admirably direct: protest everyone. Peterson recognized that although the Academy was not the institution granting jobs, it was the one defining success.

The day of the Awards show, Peterson and nearly 125 other protesters gathered in front of the Civic Auditorium in Santa Monica. Before the program began, the Santa Monica police not only arrested 12 picketers, but strong-armed them, injuring a man named Cassius Weatherby, whom they placed in a stranglehold, as an LA Sentinel photograph reveals. While West Side Story (1961) swept the awards, Peterson’s fellow demonstrators sat in prison, released only after the show had ended. Peterson and his allies argued their right to public assembly both at the time of arrest and later in a lawsuit filed against the Academy and the Santa Monica police for more than $1 million. But a judge upheld the view of the arresting officers and the Academy—that the protesters were “trespassing.” Though they had never entered the auditorium, the judge argued that, in stepping from the sidewalk onto the red carpet, they had violated private property. This battle, one in which the Academy succeeded in defining public space as private, highlights many of the tensions that lie behind the continuing Oscars struggle—tensions between public and private interests and spaces, white authorities (whether in tuxes or uniforms) and black aspirants (whether actors or activists). The physical corporeal fight for the space in front of the Awards show highlights and points to the ongoing struggle over the black body in Hollywood—one waged as much for physical as representational space. In 2016, as in 1962, some black actors are unwilling, and perhaps unable, to celebrate the year’s box office victory amidst the reality of continuing and un-redressed racial exclusion.

Now is an apt time to look back on Caleb Peterson’s protest, both as an antecedent and as inspiration. His strategy, which turned Hollywood’s moneymaking spectacles into race relations controversies, smartly used theatricality as a tool for protest. While Peterson’s protest was not explicitly leftist and his impact on equal hiring practices was unclear, it can still be read as radical and successful. Peterson was among a small group that risked potential movie careers to engage in direct action that brought the industry’s racism onto the national stage through coverage in the national black press and in some white newspapers. His choreographed encounters with the Hollywood establishment were designedly invasive and media-bound; they converted the industry’s sartorial displays of luxury and boy’s club prestige into dramas of racial injustice and demands for inclusion. Peterson’s protest demonstrates the value of unaligned, “fed up” radicalism to the struggle to reform Hollywood because it ignited a flame in response to black absence (in employment and on the screen) rather than the far easier target of racist representation. In rejecting Hollywood’s white normalcy, it had the potential to reset the standard for overarching treatment of black actors on and off-screen. Peterson’s protest, like the protest this year, was designed to push the industry in a direction that is good for it, and for the broader project of “democratic filmmaking”—an enterprise that is global in scope and that must equally train, employ, and reward those marginalized communities that award-winners want so much to thank.