How the Enslaved Came to Celebrate Independence Day

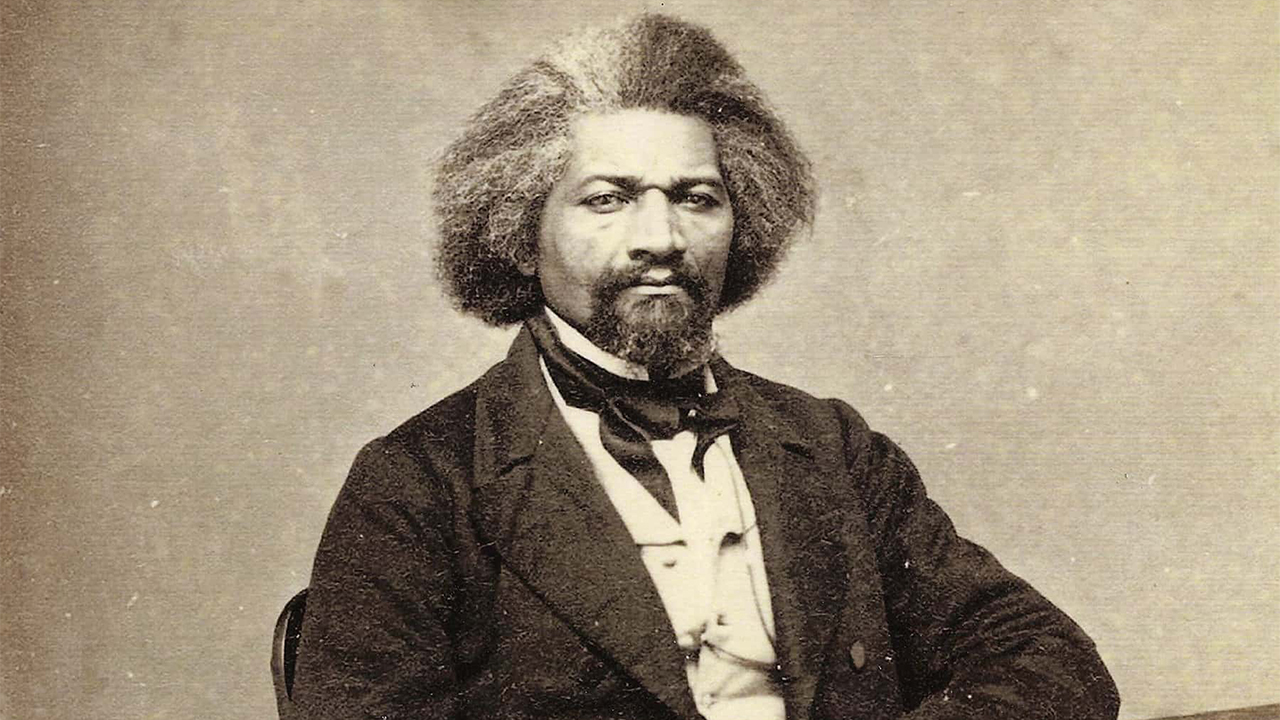

The Fourth of July seen through the eyes of African Americans Frederick Douglass and George Moses Horton.

By Cecil Brown

June 26, 2020

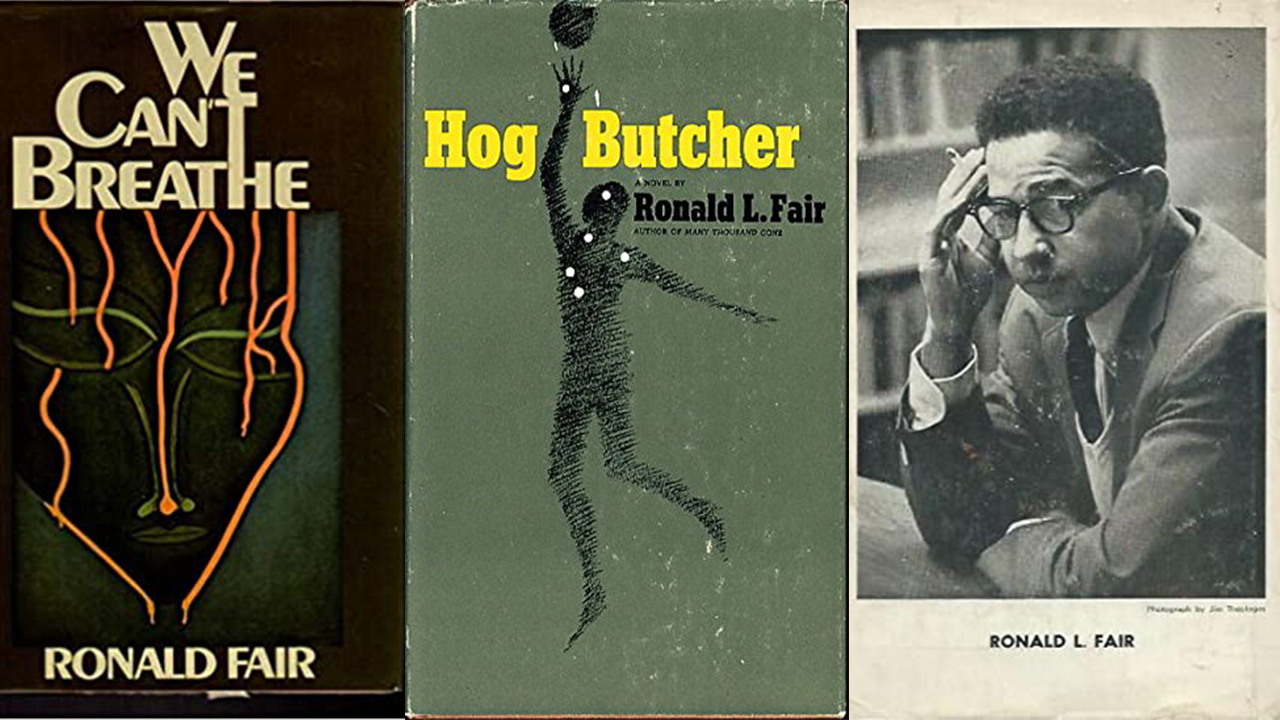

Many of us know about the famed black orator and writer Frederick Douglass’s speech in which he addressed the question of what does the Fourth of July mean to a black American; but few know about the poem, “For the Fourth of July, 1865 ” by George Moses Horton, a slave poet, who was freed in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in 1865.

On July 5, 1852, Douglass spoke at an event commentating the signing of the Declaration of Independence at Corinthian Hall in his hometown, Rochester, New York.

“Do you mean to mock me, citizens,” he asked his mostly white audience. He gave a blistering and surprisingly modern analysis of racism. He said, “This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

Douglass’s lecture was delivered at the height of the antebellum period, but Horton’s poem was written within weeks of slavery’s death throes. Horton wrote the poem weeks after he had walked forty miles from the Pittsboro plantation in North Carolina to join the Union army. Born into slavery in 1794, he knew what it was like to yearn for freedom. Forbidden by law to learn to read or write, he produced an oral style of poetry about love that impressed the students at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and that made him famous—on campus, at least.

Douglass’s lecture was delivered at the height of the antebellum period, but Horton’s poem was written within weeks of slavery’s death throes.

Caroline Hentz, a novelist and a professor’s wife, who helped Horton learn to write, got him published in her hometown newspaper, in Lancaster, Mass. Thus, Horton began his fame as a written poet.

In 1829, he published the first book of poetry, The Hope of Liberty, by a slave. Among those twenty poems was one extraordinary gem, “Liberty and Slavery,” the first explicitly antislavery poem by an enslaved person.

With the publication of this book, he began his campaign to get himself free. He wrote letters to the most important abolitionists in the United States, such as William Lloyd Garrison and John Greenleaf Whittier. He wrote to the Governor and he wrote to President Swain of UNC.

Pleading and begging, but to no avail.

Then comes the Civil War, the troops marching into the university town, and Horton, with them (having befriended Captain William Banks, a poetry lover), and now, almost seventy years old, he walks over to the Union line and he is free.

It is in this context that Horton, like millions of Black slaves, saw the Fourth of July as a celebration of freedom for celebration.

He begins:

To-day you make your choices,

Lift up your hearts and voices,

And every heart rejoices.

On this triumphal day.

Horton saw the Fourth of July as a celebration of white Americans, too. He would have agreed with Douglass that the Fourth of July meant something special to white Americans. But it meant something special to African Americans, too.

Back in 1843, he had been invited by the students of the university, to give a speech on the sacred holiday.

One of the students, Thomas Miles Garrett, wrote in his diary on July 4, 1849, this reference to Horton: “The students who remained upon the Hill thought that they would not let the ‘ourth’ pass without some noise, and accordingly held a meeting and appointed George[Horton] alias the N. Carolina bard to deliver the oration. ..”

Horton showed up. Garrett described Horton as he appeared that morning. “This morning the Poet arrived and about 11 O’clock we formed a procession and conducted the orator upon the stage.” Horton gave a speech. “It was short,” Garrett wrote in his diary, “but the applause was half an hour.” ¹

It is safe to say one of the reasons Horton’s presentation was so short was that he wanted to make the point that he was still a slave.

“He made a speech of about 5 minutes length, to the great disappointment of all present,” Garrett went on to say, “who expected a long oration. The loud, long, and repeated applause occupied however about 15 minutes. With this the celebration of the day ended.” 2

It is safe to say one of the reasons Horton’s presentation was so short was that he wanted to make the point that he was still a slave.

But now, some twenty years later, in the spring, 1865, things were for George Moses Horton—a lot different. The difference was that the black man was now free. Now we can really celebrate the true meaning of the Fourth of July.

Now let the proclamation,

Break through the land and nation,

The trump of free salvation,

Aloud the cause display.

Salvation is the sweetest song,

That ever broke from mortal tongue,

It fills the whole seraphic throng,

Throughout the worlds above;

What more can please by land or sea,

Than that which sets the bond-man free.

In the next stanza, he envisions an image of west African iconography of an African praying to Shango, he claims a victory for the mythology of Christianity as well.

Lift ev’ry hand, bend ev’ry knee,

Swell every heart with love.

We solemn this should mention,

It is the Lord’s invention,

To take the world’s attention,

The sound of victory won;

The labor is at leisure,

’Tis pain turned into pleasure,

A shower of gold and treasure,

Now falls below the sun.

The liberation event is so extraordinary that it like having the sun fall from the sky.

To-day, July the 4th, proclaim

The day of celebration,

It lifts into public fame,

Demanding jubilation,

O, let the sun rise not to set,

And we remain .where first we met,

Never for mortal to regret,

A scene to last forever.

Aloud and for the cannon’s roar,

The triumph of the Western shore.

Oppression’s voice be heard no more,

Hence to disturb us never.

For Horton, and millions of blacks, this was the real truth behind the event. For them, it was not just the slaves were free, but the whites as well. Horton ends the poem with this message.

Whig, democrat or tory,

Each heart beats high for glory.

The most delightful story,

Is this of all the three;

The Union is our mother,

We hence should love each other,

The sister and the brother,

Rejoice we all are free.

The optimism expressed here is before Horton boarded a train in 1865 and disembarked in Philadelphia, a city with a population over 674,000, with 22,000 blacks, hovering, as it were in the Seventh Ward, the first northern ghetto.

Douglass saw the Fourth as a mockery, because he was still a slave, but Horton saw Independence Day as one to be celebrated as a victory for all. As indeed it was.

1 Richmond, Merle A., Bid the Vassal Soar: Interpretive Essays on Phillis Wheatley and George Moses Horton, (Howard University Press, 1974) p. 156

2 Ibid.