Conspiracy Poet in Outer Space

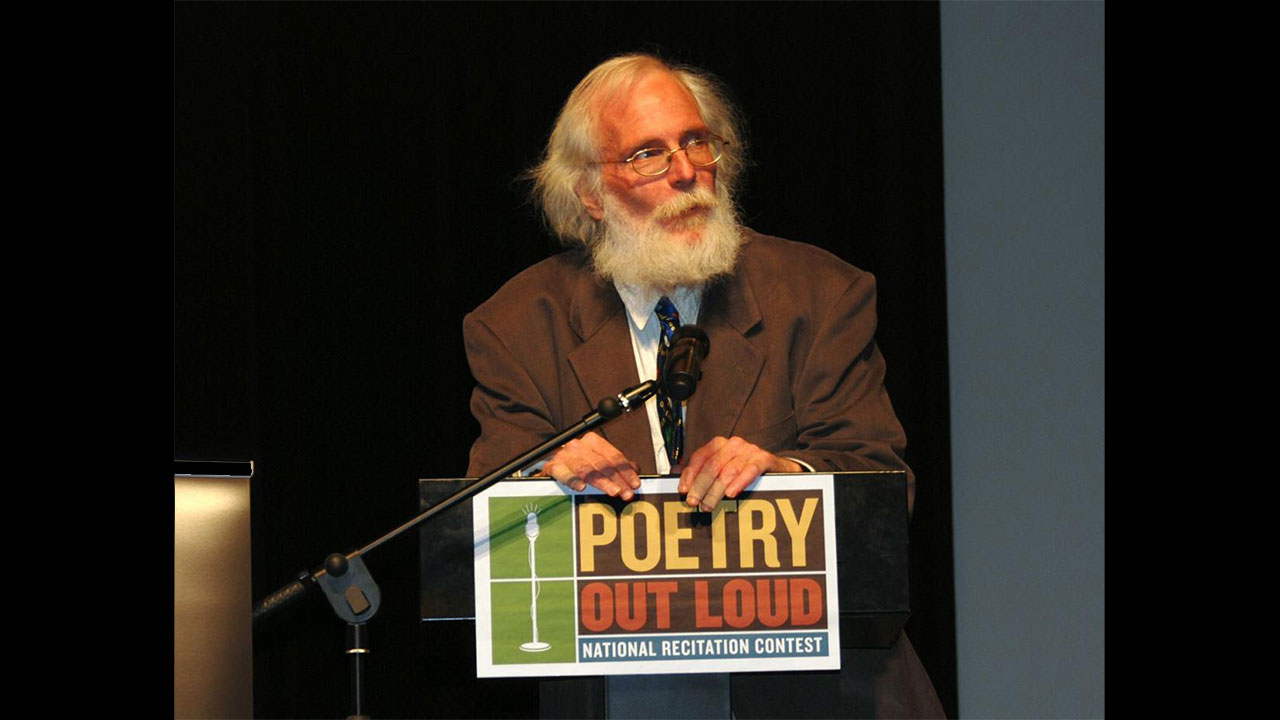

A tribute to David Clewell, 1955-2020.

By Chris King

February 27, 2020

David Clewell, who died on February 15, 2020, at age 65, is a historical figure by virtue of his appointment as Missouri’s first poet laureate (2010-2012). Clewell was appointed by Governor Jay Nixon, though, as he told friends at the time, First Lady Georganne Nixon was the real driving force behind the whole poet laureate thing. Clewell, the least official of men and poets, was not the sort to go seeking any government position, and it is entirely possible to imagine him declining the opportunity had he not been struck by the first lady’s sincerity.

Clewell—as he always narrated himself, never “David”—deserves a wider national reputation as a poet, in addition to his official state recognition and being widely adored (and, now, mourned) in his adopted home city of St. Louis. His books, mostly published by the University of Wisconsin Press (though he did get one look from mighty Penguin), deserve the widest possible readership. Clewell wrote poetry with a long line that was very easy to read and begs to be read aloud. If almost every phrase were not so pithy and memorable, you could almost call him a prosy poet. Certainly, he was a masterful narrative poet telling in verse stories that are easy to follow and often dedicated to subjects of popular fascination: the assassination of President Kennedy, CIA manipulations and machinations, unidentified flying objects and their alleged terrestrial witnesses.

There was a time in the late 1980s and early 1990s when Clewell would appear at the quirky Soulard Culture Squad’s downhome and boisterous open mic nights. Lenny Smith, the wild-eyed emcee of the culture squad, was an exuberant fan of Clewell’s praise song to vegetable vendors at Soulard Market, and it was fitting to see this large, rather shaggy man perform in Soulard at the Preservation Hall his hymn to the village market and its denizens that set up their stalls just down the street.

A wider national and international recognition never quite found Clewell. This is not so surprising for a poet in the Midwest teaching at a university (Webster University) with an international campus system but not necessarily a national name for supporting important writers, who published mostly with a Midwestern university press (and a chimerical local imprint named after garlic). It is, however, an enormous waste for such an accessible and entertaining poet to remain something of a state secret. Because Clewell is a historical figure in Missouri and ripe for discovery by readers of the English language anywhere, I will focus my tribute to this great poet and good personal friend on my direct participant observations of the man and his work, in hopes that these notes might inform future historians.

Clewell first came to my attention as a local performance poet. He soon would withdraw and become a homebody and family man, with his wife Patricia and son Ben becoming increasingly important as subjects and heroes of his shorter poems. But there was a time in the late 1980s and early 1990s when Clewell would appear at the quirky Soulard Culture Squad’s downhome and boisterous open mic nights. Lenny Smith, the wild-eyed emcee of the culture squad, was an exuberant fan of Clewell’s praise song to vegetable vendors at Soulard Market, and it was fitting to see this large, rather shaggy man perform in Soulard at the Preservation Hall his hymn to the village market and its denizens that set up their stalls just down the street.

I became Clewell’s literary critic in 2000 when his new book (Jack Ruby’s America, Garlic Press) was handed to me at the alternative weekly newspaper where I freelanced. The paper had a staff writer (a decent poet himself) who was expected to cover books, but he and Clewell had fallen out. This poet-critic wanted nothing to do with another Clewell review and tussle. For a generally genial man and loving friend, Clewell had principles and scruples and more than a little New Jersey wise guy in him, and he was quite capable of getting into literary scrapes and skirmishes, which may or may not have limited his potential fame. Whatever the staff writer had written that rubbed Clewell the wrong way, my critical enthusiasm for his poetry seemed to recommend me as an ally, and our friendship commenced.

“David Clewell may be the most open-armed and open-hearted poet writing well in English these days,” I opened my Washington Post review. “Clewell’s is the art of the embrace, encompassing and warming his subjects.” I stand by that assessment of his poetry today.

I managed to take my enthusiasm for Clewell’s poetry national a few years later in pitching and securing an assignment to review his book The Low End of High Things (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003) in the Washington Post Book World, its literary supplement that is no longer extant. I want to believe that I provided full disclosure to my editors, and given that both of them (oddly) hailed from St. Louis, they would have known how small our literary scene is and how unavoidable it was for Clewell and me to know one another personally. Regardless of any conflict of interest, I have my own literary scruples and principles and would never praise a book that was not praiseworthy. “David Clewell may be the most open-armed and open-hearted poet writing well in English these days,” I opened my Washington Post review. “Clewell’s is the art of the embrace, encompassing and warming his subjects.” I stand by that assessment of his poetry today. My having personally experienced his open arms and heart was an enormous gift, but a separate matter from appreciating his poetry.

My opportunity to work creatively with Clewell followed upon my championing another state poet laureate who deserved national recognition that never quite came his way. Leo Connellan—a poet of Maine, in fact, just as Clewell was all New Jersey, never Missouri—was appointed poet laureate of Connecticut in 1996, long before Missouri thought to install the ceremonial honor on anyone and anointed Clewell. With fellow musician friends, I recorded Connellan performing his hitchhiking epic Crossing America (Penmaen Press, 1976) and then commissioned musical scores to sequence as interludes in between the poet’s reading of the epic’s sections. This approach delighted Clewell, who detested—remember those literary principles and scruples and grudges?—the sound of music noodling over or behind the performance of poetry. But he loved music as interlude interspersed throughout Leo’s long poem, and he had a true fanboy’s enthusiasm for Connellan and an infectious excitement to find others who honored a fellow master poet who had been somewhat neglected by the fickle, inbred, backbiting poetry business.

Given that Clewell also wrote long poems and given that we continued to set long poems to music, it was perhaps inevitable that I would eventually pitch a project to Clewell and that he would go along with it. We hatched our plan over lunch at a joint called Hugo’s, near the campus where he taught for decades. Fittingly for a meeting with this poet of the dingy and quotidian, Hugo’s had the ambience of a dive bar—and not the quaint kind sometimes resuscitated by hipsters. Clewell prized Hugo’s for having the best hamburgers in town. It is always puzzling the things one does and does not remember about the important moments in one’s life, and getting Clewell to agree to do this project with us was very important to me, but I remember being served a boring hamburger with the single most ghastly and stale white buns ever clamped around a beef patty.

I saw David Clewell up on stage delivering his poetry, entranced, almost, to experience a world he had imagined coming alive around him.

His poem that he agreed to perform for us so that we could score and sequence music throughout it as interludes was Jack Ruby’s America, which I had reviewed a decade earlier, his unforgettably hilarious and moving portrait of the Jewish club owner in Dallas who killed Lee Harvey Oswald. For the score we worked with local jazz players, a modern klezmer band from Chicago (Ruby‘s hometown) memorably named Yid Vicious, and archival noir rock from Los Angeles. Our arts organization Poetry Scores had a snakebitten history of starting projects with poets (it must be said, older poets) who died before we finished our musical score of their work. On Jack Ruby’s America, we were so pleased to have a living, breathing poet to celebrate the finished record release with us that I asked Clewell to perform the poem live with a jazz burlesque score.

Ruby was a burlesque club owner, which is central to Clewell’s portrait of the petty mobster. St. Louis then had a thriving burlesque scene where I had many close friends. We had no budget to fly Yid Vicious in from Chicago, and the noir rockers from Los Angeles had long ago disbanded and one had died, so we built our entire live score around local jazz musician Dave Stone’s band and local burlesque star Lola Van Ella. We packed one of our favorite clubs in St. Louis that night and really made Clewell proud. I saw David Clewell up on stage delivering his poetry, entranced, almost, to experience a world he had imagined coming alive around him.

At the end of the show—while the poet very agreeably participated, like any other gigging performer, in the obligatory divvying up of door proceeds—he went around the emptying club emotionally thanking the musicians and Lola, our burlesque star. Clewell could be a little gruff and withdrawn with people he did not know well, so it was one of the highlights of my career as an impresario to draw him out on the stage with a sexy burlesque artist and jazz band to perform his masterpiece portrait of a burlesque club owner and then to see him celebrate so warmly afterwards with these people he did not know.

Our project with Clewell and his aggressive approbation of working with us caught the attention of Pete Genovese, the publisher of Garlic Press, which had been publishing the Clewell manuscripts he could not place with the University of Wisconsin (or did not even bother sending out of town). I was amazed when Genovese offered to bequeath Poetry Scores the entire Garlic Press inventory, which included many dozens of copies of a handful of David Clewell titles. Of course, I accepted, delirious with gratitude, although this acceptance would lead to my first experience of Clewell as scrupulous curmudgeon. Genovese had warned me that the title I would find most attractive—his edition of the poem we had scored, Jack Ruby’s America—had just about devastated Clewell when the glue holding the book together came unglued. I should have listened more closely to Genovese when he told me that I had better talk to Clewell first before I tried to do anything with those boxes and boxes of his (now, our) gorgeous edition of Jack Ruby’s America.

The next time I saw Clewell, I was toting a copy of the Garlic Press edition of Jack Ruby’s America, and the poet became—it is not overstated to say—enraged at the sight of it. He told me to put the book away and to do nothing whatsoever with the other copies of the book, muttering something to the effect that he had told Genovese to destroy them. It was then that I could hear in my head something Genovese had said that clearly I did not take seriously enough: “Clewell thinks this edition is cursed.” While I did not think at the time that Clewell held this incident against me or folded me mentally into the curse of the bad glue that foiled the first publication of one of his favorite poems, I realize now that I am unable to recall a more recent memory of being alone with David Clewell and enjoying his inimitable and unpredictable conversation. That may have been the last time he spoke to me.

David Clewell wrote about these arcane and far-fetched subjects with the sense of humor that infused all of his work and which made it questionable how seriously he took any of this stuff other than as good material for poetry. But he also wrote with real compassion about the people caught up in conspiracy theories, both as alleged actors and theorists, and people who seemed to believe that they have been touched by an alien. Clewell made you believe in their belief, if not necessarily in the veracity of those beliefs.

I have a quirk where I like to invite significant people who are not baseball players to autograph baseballs for me. I do this with poets a lot. I have baseballs signed by the Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka, the Pulitzer Prize-winning Paul Muldoon, and Talat S. Halman, the man who translated all of Shakespeare into Turkish. Inaugural Missouri poet laureate David Clewell did more than just sign my baseball. He also made a drawing on it. Clewell was somewhat notorious (and somewhat basked in this notoriety) for being pretty far out there on conspiracy theories and extraterrestrial visitations to Earth. He wrote about these arcane and far-fetched subjects with the sense of humor that infused all of his work and which made it questionable how seriously he took any of this stuff other than as good material for poetry. But he also wrote with real compassion about the people caught up in conspiracy theories, both as alleged actors and theorists, and people who seemed to believe that they have been touched by an alien. Clewell made you believe in their belief, if not necessarily in the veracity of those beliefs.

That is the backdrop and inside joke for what he sketched on my baseball that he autographed, which was an outer-space ship. He drew the spaceship on my baseball at the bar top at Hugo’s while I winced my way through that egregiously overhyped hamburger and the curse of its supernaturally stale, white-bread, sesame-seedless bun.

David Clewell was a consummate humanist with an overwhelming belief in the dignity, possibility, and hilarity of human beings. He was not, to my knowledge, a devout believer in any faith that would postulate an afterlife that he is now enjoying. It is, however, my belief that Clewell believed he would survive in his poetry, which indeed should last as long as the language, and in the memories of the many, many people who cherished him and who miss him terribly now. But I am among the hopeless and deluded dreamers David Clewell believed in, and so I choose to believe that there is a starship in the sky that touches down and takes away great poets who were perhaps not as widely celebrated on Earth as their work deserved. And that spaceship is far out there now on an interstellar tour, where Clewell is packing starlit houses night after night, and on some far distant planet he is going live right now with a burlesque dancer on one arm and a poem in his other hand.

More realistically–for, as far-out as Clewell could get in his poetic practice, he always came back home to common sense and goodness—David Clewell died unexpectedly in his sleep. I like to think he is still only dreaming that he died.