Is Democracy Possible Today?

James Baldwin’s love letters to his "innocent and criminal countrymen”

September 23, 2019

I. James Baldwin’s Now

“Why is my freedom, my citizenship, in question now?”¹ When James Baldwin was alive, he frequently called on his fellow citizens to acknowledge that their sense of time was dangerously out of step with history. Most famously, when he prophesied “the fire next time,” Baldwin noted that the celebration of the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation was 100 years premature. Americans were not only too early in their embrace of racial equality, however. With equal vehemence, Baldwin argued that most citizens, particularly white ones, were forever late. Their gestures of deferral guaranteed that change would not come soon enough—if at all—and that generations would languish while “progress” took its time. It is no accident that Baldwin’s voice has been summoned by so many artists, intellectuals, activists in recent years to give shape to their outrage at the abandonment of entire communities and to voice a plea for real democracy. The span of Baldwin’s life (1924-1987) ended before the idea of a “postracial” polity took hold, but he would, I think, be neither persuaded nor surprised by the degree to which widening gulfs between the poorest African Americans and most white Americans have been accompanied by the insistence that it is time to get over the past. After all, variations on the exhortation to “get over it” were familiar in Baldwin’s own time, even before the landmark achievements of the civil rights movement. His writing presses us, again, to reset our clocks so that they reflect more accurately the timing of democratic aspiration and racial justice.

My own initiation into the force of Baldwin’s words came shamefully late. I was a first-year doctoral student when I first really encountered his writing. Reading Baldwin’s “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” in a seminar on “The Afro-American Intellectual Tradition,” was both destabilizing and thrilling. The thrill was in the prose, in Baldwin’s capacity to wed the intimate and the universal and to make of his life an offering to generations of readers, including those whose experiences were far removed from his own. But the destabilization mattered more. Baldwin’s language upended the order of my understanding, as a political theorist-in-training, and as a white American. Where political theorists and other students of politics have largely looked away from the everyday aggressions and the systemic violence that shape the experiences of nonwhite citizens, Baldwin demands that we reexamine familiar concepts—equality, freedom, citizenship, responsibility, democracy—in ways that do justice to those experiences. Coming to terms with The Fire Next Time during my first semester of graduate school, in the midst of Clarence Thomas’s vexed nomination to the Supreme Court and in the interval between the beating of Rodney King and the acquittal of his attackers, required that I confront the extent of my own innocence. The currency of Baldwin’s nearly 30-year-old critique pressed me to see that every year yields stories, told and untold, about the degree to which white supremacy holds us in its grip.

The thrill was in the prose, in Baldwin’s capacity to wed the intimate and the universal and to make of his life an offering to generations of readers, including those whose experiences were far removed from his own. But the destabilization mattered more.

Nothing in Baldwin’s essays should have been news, of course. I had been studying moral questions in political life through four years of college and two years of divinity school, but my classes and research had touched only glancingly on questions of “race.” More, I was from Baltimore, an emblem of racialized blight and abandonment well before the city captured the attention of an aghast nation in the spring of 2015. I was alive (if only a toddler) at the time of the 1968 riot/rebellion/uprising that tore up black neighborhoods, left six people dead, and helped catalyze Spiro Agnew’s rise to the White House. Like many Americans, however, I grew up in an almost entirely segregated world. Friendships with African American classmates offered the illusion of integration; but day-to-day existence in the area known as the Greenspring Valley was white and comfortably well-off. If Baltimore lacked any address as storied as “the renowned and elegant Fifth [Avenue],” Baldwin’s keen observation about the gulf between the world of department stores and museums that was off-limits to him and his own, uptown, “wide, filthy, hostile Fifth Avenue,” might as easily capture the divide between the privileged precincts of Baltimore County and Roland Park, where I lived and went to school, and the terrifying “Old Baltimore” sketched by Ta-Nehisi Coates.² Once I learned to drive, I ranged freely across the city, to Memorial Stadium, the Enoch Pratt Free Library, and summer jobs downtown. But whole regions of Baltimore were off my map. They were unknown until I was introduced to them through Homicide and The Wire, along with the rest of the TV audience. This is not to say that I did not inhabit the city Coates describes or that I did not bear responsibility for it; only that I did not know any of that at the time.

One dimension of knowing is grappling with the living power of Baldwin’s words, asking how they give shape to the new and not-so-new inequities and violences of today. There are risks to such appropriation, of course: it is possible that the beauty of Baldwin’s phrasing and the depth of his investment in an idea of American democracy make him too available for purposes that run counter to his own. Several years ago, around the time that Richard Rorty’s Achieving Our Country appeared,³ I was nagged by a sense that references to Baldwin seemed to pop up whenever a commentator sought to embellish an argument with an elegant sentence or two about race and democracy. I even started to conceive a dyspeptic essay called “Everybody’s Epigraph.”The complaint mirrored my unease with the equally omnipresent and often gratuitous references to Du Bois’s proclamation about “the problem of the color line,” which seemed to get us no closer to honest engagement with the sheer difficulty of imagining and realizing a multiracial polity. Just how far, I wondered, were Baldwin’s admirers willing to go?

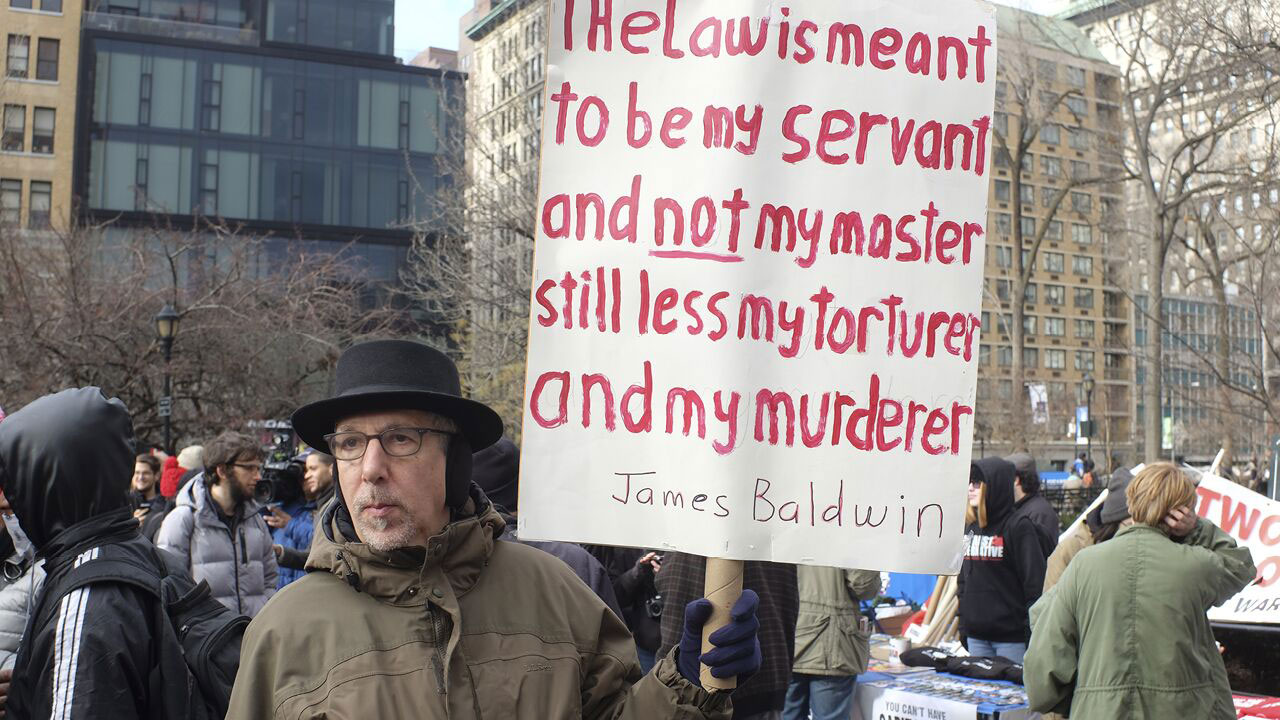

That question has been resoundingly answered by contemporary appeals to Baldwin’s witness. At a time when unpunished acts of official and unofficial violence against black women, men and children, far from abating, recur with crushing frequency, and racial inequalities appear permanently entrenched, Baldwin seems to be everywhere. And the renewed appreciation for the force of his post-1963 writings, in particular, strikes me as an indication—urgent and profound—of his value as a counterweight to the common sense of the contemporary moment. To ask, again, why and how Baldwin assists us in understanding the unfinished work of democracy, I explore two elements of his writing during the period that followed the major civil rights victories of the 1960s. On the one hand, I consider what may have been the greatest exemplification Baldwin’s love for humanity: his willingness to keep writing in the face of scorn and dismissal. His courage, in other words, to be unloved. Rereading No Name in the Street, the extended essay that appeared in 1972, in a period when Baldwin felt unmoored and unwell, exposes his doggedness in sticking with a project whose completion was so painful that he likened it to being impregnated by the “Mighty Mother Fucker.”⁴ Complete it he did, even as he believed that neither white nor black readers wanted to hear what he had to say. On the other hand, I suggest why Baldwin’s appreciation for the dangers of categorical thinking, a concern he exhibits across his entire career, is particularly essential in a time that revels in its own “post-”ness. Countering the wishful thinking that we have gotten over the crimes of the past are two contemporary figures whose distinctive voices have caught Baldwin’s spirit and show us how out of step with history we continue to be: Ta-Nehisi Coates and Claudia Rankine.

II. Loving and being unlovable

The centrality and force of love, democratic love, is at the core of Baldwin’s writing. As both his admirers and critics have noted, Baldwin not only embraced the kind of other-regarding love that propelled Martin Luther King’s political campaigns, but he spoke passionately on behalf of the full-bodied, erotic, stinking love that, for King, was always subordinate to agape.⁵ Beyond this, Baldwin enacted the love he advocated through his willingness to take risks on its behalf. To love, by his account, is to be “both free and bound” (461)—free to confront life’s deepest challenges because the binding embrace of the beloved promises you the safety of home. Yet what follows when one’s lover is untrustworthy? When he published No Name in the Street, Baldwin faced precisely this question, not only in the uncertainties of his romantic life but also in the dismal evidence that people who had bought his books and praised his talents had little interest in heeding his words. Indeed, one of the greatest testaments to the depth of Baldwin’s love is the sheer fact of his persistence. Time passed, fashions changed, and still he wrote. Indeed, among the many gifts Baldwin gave his readers, one of his greatest was the courage to be unlovable, to present himself to a world that neither prized nor reciprocated his gifts. The astonishment of Baldwin’s going on is captured, appropriately, by Amiri Baraka, who once derided the older writer as a “Joan of Arc of the cocktail party,”⁶ but whose eulogy for Baldwin illuminates the profundity of his vocation: “Attacked or not, repressed or not, suddenly unnewsworthy or not, Jimmy did what Jimmy was.”⁷

The currency of Baldwin’s nearly 30-year-old critique pressed me to see that every year yields stories, told and untold, about the degree to which white supremacy holds us in its grip.

“Jimmy did what Jimmy was.” That commitment is vividly on display in No Name in the Street, which appeared when Baldwin was no longer a rising talent but a middle-aged gadfly, who refused to smother his outrage or hide his sexuality and who redeployed both to alert his readers to dangers they courted with apparent insouciance. When No Name in the Street appeared, Baldwin had already endured the barbs of Baraka and other black activists who reviled him for his sexuality and distrusted his success as “the Great Black Hope of the Great White Father” (498). He had also weathered the dismissal of white critics, who mourned the end of Baldwin’s creative powers and were suspicious of his increasing willingness to speak openly of “Black Power.” Still, Baldwin kept writing, even at the risk of having his gifts scorned, once more, as the work of “the odd and disreputable artist” (540). He even laid claim to his homosexuality, which had never been a secret, when he owned his status as “an aging, lonely, sexually dubious, politically outrageous, unspeakably erratic freak” (458).

Baldwin’s willingness to perform acts of public love—by which I mean criticism—models a form of democratic citizenship that offers a necessary rebuttal to “that emancipated North which, but only yesterday, was so full of admiration and sympathy for the heroic blacks in the South” but whose complacency is not shaken when Black Panthers are “menaced, jailed, and murdered” (535). His writing speaks with equal urgency to the satisfied heirs of those innocents in the age of Obama. Talk may be cheaper than ever but it also feels more dangerous at a moment when the speed of transmission and heightened scrutiny of any reference to race mean that missteps can go global within seconds. Part of Baldwin’s legacy is his willingness to say the wrong thing, if it is in the service of discerning what the right thing could be. He might not have been subject to internet shaming campaigns or the vicious speed of social media rejoinders, but he embodied the responsibility of bearing witness, whatever the costs.

I am struck by the degree to which No Name in the Street serves as a monument to those costs. Its title announces the anonymity of the vantage from which the book proceeds, as though nobody has yet learned to use Baldwin’s name. And the names that fill its pages provide an index of both the famous and unknown casualties of American innocence and the struggle to overcome it. In addition to Medgar, Malcolm, and Martin, No Name in the Street recalls the police killings of Bobby Hutton, Mark Clark, and Fred Hampton, the suicide of Baldwin’s best friend, Eugene, the slow death of his stepfather, the imprisonment of Tony Maynard, and the sad rambles of a man who calls himself the Prince of Abyssinia. It also exposes and explores Baldwin’s own wounds, the price of failure, exhaustion, sorrow, and alienation. He vivifies the impact of those losses by tracing the itinerary of a dark suit that he bought for an appearance with King at Carnegie Hall in 1968. Within a few weeks, Baldwin wore the suit again—at King’s funeral—and then he delivered it to an old friend, once his best friend, from whom he was permanently estranged. Deftly, Baldwin transmogrifies a bit of tailoring into a meditation on the visible and invisible injuries that the polity inflicts on both its citizens and those it supposes to be its enemies. And yet, and despite all this, “Jimmy did what Jimmy was.”

The astonishment of Baldwin’s going on is captured, appropriately, by Amiri Baraka, who once derided the older writer as a “Joan of Arc of the cocktail party,” but whose eulogy for Baldwin illuminates the profundity of his vocation: “Attacked or not, repressed or not, suddenly unnewsworthy or not, Jimmy did what Jimmy was.”

To say that Baldwin’s persistence is evidence of his willingness to commit wholly to the work of love is not to diminish his keen awareness of the work love could not do and the ways it could be deployed as a decoy for meaningful action. Changing Americans’ habits of the heart, in other words, is no substitute for eliminating political repression, addressing entrenched poverty, or putting an end to the criminalization of blackness. When Baldwin relates his admiration for the Black Panthers, for example, he praises their focus on “land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace” (537); at the same time, he undermines the kind of facile invocation of love (“the American piety”) that is revealed in the observation of a potential white juror in the trial of Huey Newton: “As I said before, that I feel, and it is my opinion that racism, bigotry, and segregation is something that we have to wipe out of our hearts and minds, and not on the street” (533). “One can wonder to whom the ‘we’ here refers,” Baldwin muses, “but there isn’t any question as to the object of the tense, veiled accusation contained in ‘not on the street’” (533). Before we can wipe out anything in our hearts and minds, Baldwin avers, we need to confront the deliberate construction of American ghettoes and the message they unerringly convey: that “white America remains unable to believe that black America’s grievances are real” (536). Doing so demands a willingness to take responsibility for mistakes and unearned privileges, to make the gesture of solidarity without the expectation of gratitude or admiration, to risk not being loved in return.

III. Categories and their afterlives

In April 2015, nearly 30 years after Baldwin’s death, the nation was transfixed anew by scenes of destruction in Baltimore. The unexplained but hardly mysterious death of Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old African American man in police custody (for making criminal eye contact with a police officer?), set off days of peaceful demonstrations. But cameras and commentators did not arrive in full force, until rocks and flames incited pious calls for nonviolence and reaffirmed familiar narratives of urban decay and lawlessness. By that time, the leader of Baltimore’s police union had likened (nonviolent) demonstrators to a “lynch mob,” alchemizing a history of white racist violence into a threat posed by multiracial protest. And soon afterward, Baltimore’s mayor and the American president, both black citizens themselves, sought explanatory authority through the language of “thug.”That this language was so readily available to racial liberals—and not simply to the right-wing commentators who rushed to vilify Ferguson, Missouri, police-shooting victim Michael Brown as a “thug”—intimates the degree to which blackness and criminality remain intertwined in the public imagination.⁸ Much has changed since Baldwin dissected the violent policing and smashing of earlier ghettoes. Yet Baltimore exposed the continuing price of what Baldwin would have readily diagnosed as a terrible imbalance between forthright condemnations of black political activity, on the one hand, and “the democratic circumlocution” (491) that disguises official and unofficial acts of white criminality, on the other.

Baldwin was always suspicious of categories, particularly race and color, which he understood to be traps.⁹ At the same time, he was equally adamant that the workings of those categories could not simply be wished away. Had he lived to see it, I think that there is little doubt that he would have readily pierced the wishful thinking of post-racialism and diagnosed the twenty-first century penchant for “post”-ness as the newest outbreak of a too familiar affliction. Our confidence in the evanescence of old prejudices and structures of injustice reveals, in its contemporary form, the insulation from black grievances that Baldwin decries in No Name in the Street. That essay, which appeared in the early years of the treacherous slide from Civil Rights Era to “post-civil rights,” anticipates the pivot from redress to retrenchment and reversal that followed. What Du Bois describes as “phantasmagoria,”¹⁰ Baldwin declaims as fraudulent history. Today, we hear the reverberations older narratives of white goodwill and black deviance in calls for “personal responsibility” and in the insistence that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.”¹¹ Even as Americans appear to be working through the past—in public apologies for the crimes of slavery and Jim Crow, in the popularity of films and fiction that memorialize abolition and civil rights activism, in the proliferation of heroic black images, including that of Baldwin himself, on stamps and public buildings—the disconnect between our gestures and our deeper commitments makes Baldwin’s point.

To measure the vitality of the categories Baldwin spent his life questioning and find resources for relaxing their grip on us, we would do well to turn to Coates and Rankine. Without collapsing crucial differences in their writing, it is possible to see how each calls on Baldwin to penetrate the layers of historical deceit and attempt to fashion an alternative, more fully democratic American language. Coates’s 2009 memoir of Baltimore—where “they told us to act civilized, but everywhere bordered on carnage”¹²—and his social critical writings pay both explicit and tacit homage to Baldwin. Consider his 2014 Atlantic cover essay, “The Case for Reparations.”This may seem like an odd example, since Baldwin does not write in the idiom of reparations and Coates’s article, unlike so much of his work, does not directly invoke Baldwin. Still, Coates’s revival of an idea that has a long lineage in black political thought and activism effectively reminds readers (again!) what Baldwin insisted: Americans have approached the question of race and debt in backward fashion.

Coates’s article pays homage to Baldwin by deploying the first-person plural to criticize the violence of Americans’ innocence and the dangers of adherence to a fantastic history. “We believe white dominance to be a fact of the inert past,” Coates observes, “a delinquent debt that can be made to disappear if only we don’t look.”¹³ Like the first-person plural deployed so deftly by Baldwin in essays like “Many Thousands Gone,” Coates’s “we” is both inclusive and barbed. It aims directly at Atlantic readers, assured in our enlightenment and resistant to the implication that we are accountable for the ongoing devastation of black communities. “Black nationalists have always perceived something unmentionable about America that integrationists dare not acknowledge,” writes Coates,” —that white supremacy is not merely the work of hotheaded demagogues, or a matter of false consciousness, but a force so fundamental to America that it is difficult to imagine the country without it.”¹⁴ Coates’s article updates Baldwin’s assault on the effort to persuade oneself that one “does not know what [one] knows too well” (548) and draws upon the longstanding black reparations struggle as a vehicle for examining and redressing the historical injustices Baldwin implored his readers to acknowledge.

According to Coates, however, his initial formulation of the “case for reparations” was incomplete. In April 2015, shortly after the Freddie Gray protests caught national attention, Coates offered an addendum to that piece, in a forum that took place on the leafy, prosperous Baltimore campus of Johns Hopkins University. Where the Atlantic essay details the legacies of enslavement and violently-enforced segregation, of exclusion from policies designed to create and sustain a middle-class, on the one hand, and subjection to unpunished predatory behavior by landlords, employers, realtors, and banks, on the other, Coates’s comments in Baltimore take the analysis a step further. They call for a reckoning with the central role of the criminal justice system in making black people available for public and private acts of theft. “Adhering to middle-class norms has never shielded black people from plunder,” Coates observes, as if anticipating the (predictable) response by David Brooks and others who proclaim that “the real barriers to mobility are matters of social psychology, the quality of relationships in a home and a neighborhood that either encourage or discourage responsibility, future-oriented thinking, and practical ambition.” Coates echoes Baldwin in unmasking the kind of innocence that allows Brooks to regard the wreckage of Baltimore and muse that “lately it seems as though every few months there’s another urban riot.”¹⁵ By reminding a broad audience of the significance of reparations as a rebuttal to this kind of logic, Coates reformulates a question at the heart of Baldwin’s work: What would it take for the United States to become a democratic polity, and what is owed to the citizens and their ancestors who have struggled across generations to build the country without just compensation and often under conditions of domination and terror? Coates’s writing asks us to wrestle with one of Baldwin’s most provocative remarks: “I am speaking very seriously, and this is not an overstatement: I picked cotton, I carried it to the market, I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing. For nothing.”¹⁶

Where Coates traces the interplay between macro-level policies and human lives, Rankine, a poet and critic whose writing also draws upon Baldwin’s words and reveals their inspiration, requires that we attend to the intimate costs of white supremacy. Her 2014 volume, Citizen, details the hazards of interracial exchanges in the fraught context of the twenty-first century. Speaking largely in the second-person, Rankine exposes the kinship between personal attachment and policing, as white friends expect you not to trespass across the bright line between your “historical self ” and your “self self.”¹⁷ How far have we come, really, from Baldwin’s time, when simply to utter “Black Power” was to offend? The world Rankine limns with such precision is one in which Americans can be irked by the specificity of the claim that “Black Lives Matter.” Don’t all lives matter? Yes, Baldwin or Rankine might respond, but what is it about a focus on the devaluation of black people—as citizens and as human beings—that bothers you? How far have we come, in other words, from Baldwin’s comment that the white American “has his reasons, after all, not only for being weary of the entire concept of color, but fearful as to what may be made of this concept once it has fallen, as it were, into the wrong hands” (550)? Indeed, one of the undercurrents that runs through Citizen is the ongoing contest over who gets to notice race and on what terms.

Coates’s writing asks us to wrestle with one of Baldwin’s most provocative remarks: “I am speaking very seriously, and this is not an overstatement: I picked cotton, I carried it to the market, I built the railroads under someone else’s whip for nothing. For nothing.”

“Yes, and this is how you are a citizen: Come on. Let it go. Move on.”¹⁸ Rankine’s words crystallize two truths: that getting over it is a luxury no one can afford, and that the costs of living up to the command to “move on” are not borne by all citizens equally. Where Baldwin evinces an exhaustion that is almost palpable in No Name in the Street, Rankine’s prose poem registers the sighs produced by the effort simply to keep going in a polity, where the oppressed are too readily diagnosed as sick or oversensitive. Citizen begins from the point of exhaustion, “when you are alone and too tired even to turn on any of your devices.”¹⁹ And it proceeds through a series of vignettes that recount how not noticing race, as post-racialism requires, enables the reenactment of older dramas of power and disavowal through raced bodies. The impact of white demands for deniability is not only registered in exchanges across lines of color line that remain all too alive (even if they are more “complex”) but also in the body politic and the bodies of citizens themselves: “The world is wrong,” Rankine observes. “You can’t put the past behind you. It’s buried in you; it’s turned your flesh into its own cupboard.”²⁰

Rankine’s “American lyric” catalogs the harms inflicted, unthinkingly, by white power, plumbs the myriad ways that “the wrong words enter your day,”²¹and joins personal exploration to an accounting of the costs of living while black in the United States in the twenty-first century. We might call it, following historian Nell Irvin Painter’s lead, “a fully loaded cost accounting.”²² Rankine’s ledger includes Hurricane Katrina, Eric Garner, James Craig Anderson, the Jena Six, “Stop and Frisk,” Jordan Davis, Michael Brown, and more. She adds new chapters to the history of the polity in a fashion that is both Baldwinian and entirely her own. In a meditation dedicated to the memory of Trayvon Martin, for example, Rankine writes: “Those years of and before me and my brothers, the years of passage, plantation, migration, of Jim Crow segregation, of poverty, inner cities, profiling, of one in three, two jobs, boy, hey boy, each a felony, accumulate into the hours inside our lives where we all are caught hanging, the rope inside us …”²³ What Rankine’s words withhold from us, in the way of solace or the promise of reconciliation, is joined to the fact of her willingness to write (which is not to presume that she writes for us). Like Baldwin’s essays, Citizen distills the beauty in the ugliness and translates the tiresome experience of the poet’s fellow citizens’ aggressions into something that might even turn out to be “a lesson.” Her offering, in other words, is a form of social criticism that both expresses the truth and counteracts it, seeding the ground with new vocabularies of democratic imagining.

Like Baldwin’s essays, Citizen distills the beauty in the ugliness and translates the tiresome experience of the poet’s fellow citizens’ aggressions into something that might even turn out to be “a lesson.”

Rankine’s assault on today’s innocence reminds us of the miracle of Baldwin’s career and of the changes he was not able to wrest from an unwilling audience, no matter how eloquently or insistently he wrote. Remarkably, even in a period of deep uncertainty and unutterable loss, Baldwin still declared: “To be an Afro-American, or an American black is to be in the situation, intolerably exaggerated, of all those who have ever found themselves part of a civilization which they could in no wise honorably defend—which they were compelled, indeed, endlessly to attack and condemn—and who yet spoke out of the most passionate love, hoping to make the kingdom new, to make it honorable and worthy of life” (552). The quotation certainly captures something of Baldwin’s exertions and of his vocation. But it would be misleading to end the quotation there, as I did in my own book on Baldwin. For these words, which appear in the last paragraph of No Name in the Street, are just the beginning.

To stop with “life” is to follow the example of countless wishful thinkers, who have grasped the hope extended in Baldwin’s encomium to “achieve our country,” imagined ourselves as members of the “handful” who are poised to “end the racial nightmare,” and averted our eyes from the grim promise of “the fire next time!” But the gift of No Name in the Street—and Baldwin’s career—resides more fully in the warning with which the essay really ends. Black Americans, Baldwin declares, have always seen, “spinning above the thoughtless American head, the shape of the wrath to come” (552). Love gives the warning its ferocity. Baldwin does not revel in the destruction of his fellow citizens, no matter how much damage we have wreaked. And even as he foretells Americans’ likely catastrophe, his final gift is the intimation of another possibility: that in the fiery condemnations of the seer we might discern the embers of an unredeemed democratic dream.

1 James Baldwin, “The American Dream and the American Negro,” in The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction, 1948-1985 (New York: St. Martin’s/Marek, 1985), 405. Subsequent references to Baldwin’s writing will come from this volume and will be noted parenthetically.

2 Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Beautiful Struggle: A Father, Two Sons, and an Unlikely Road to Manhood (New York: Spiegel and Grau, 2009). For a history of segregation in Baltimore, see Antero Pietila, Not in My Neighborhood: How Bigotry Shaped a Great American City (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010).

3 Richard Rorty, Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-Century America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997).

4 David Leeming, James Baldwin: A Biography (New York: Knopf, 1994), 309.

5 On the “stink of love,” see James Baldwin, Giovanni’s Room (New York: Laurel, 1956), 187.

6 LeRoi Jones, “Brief Reflection on Two Hot Shots,” in Home: Social Essays (New York: William Morrow, 1966), 117.

7 Amiri Baraka, “Jimmy!” in James Baldwin: The Legacy, Quincy Troupe (New York: Simon and Schuster/Touchstone, 1989), 132.

8 For a history of this linkage, see Khalil Gibran Muhammad, The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

9 George Shulman aptly notes that Baldwin “interpret[s] identities and categories as defenses.” George Shulman, American Prophecy: Race and Redemption in America’s Political Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2008), 136.

10 See W.E.B. Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880 (New York: The Free Press, 1998), 705.

11John G. Roberts, Jr., Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1. 551 U.S. 701 (2007). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/551/701/ opinion.html (downloaded 3 June 2015).

12 Coates, The Beautiful Struggle, This essay was written before the publication of Coates’s second memoir, Between the World and Me (2015) and thus does not address the new book or the swirl of commentary it has generated.

13 Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic (June 2014), 62.

14 Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” 70.

15 David Brooks, “The Nature of Poverty,” The New York Times, 1 May 2015, A27.

16 Baldwin, “The American Dream and the American Negro,” 404. This essay is an edited version of Baldwin’s comments in his 1965 Cambridge Union debate with William Buckley, Jr. For a video version of the debate, see: https://vimeo.com/18413741

17 Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric (Minneapolis: Graywolf Press, 2014), 14.

18 Rankine, Citizen, 151.

19 Rankine, Citizen, 5.

20 Rankine, Citizen, 63.

21 Rankine, Citizen, 8.

22 Nell Irvin Painter, “Soul Murder and Slavery: Toward a Fully Loaded Cost Accounting,” in S. History as Women’s History: New Feminist Essays, ed. Linda K. Kerber, Alice Kessler-Harris, and Kathryn Kish Sklar (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), 125-46.

23 Rankine, Citizen, 89-90.