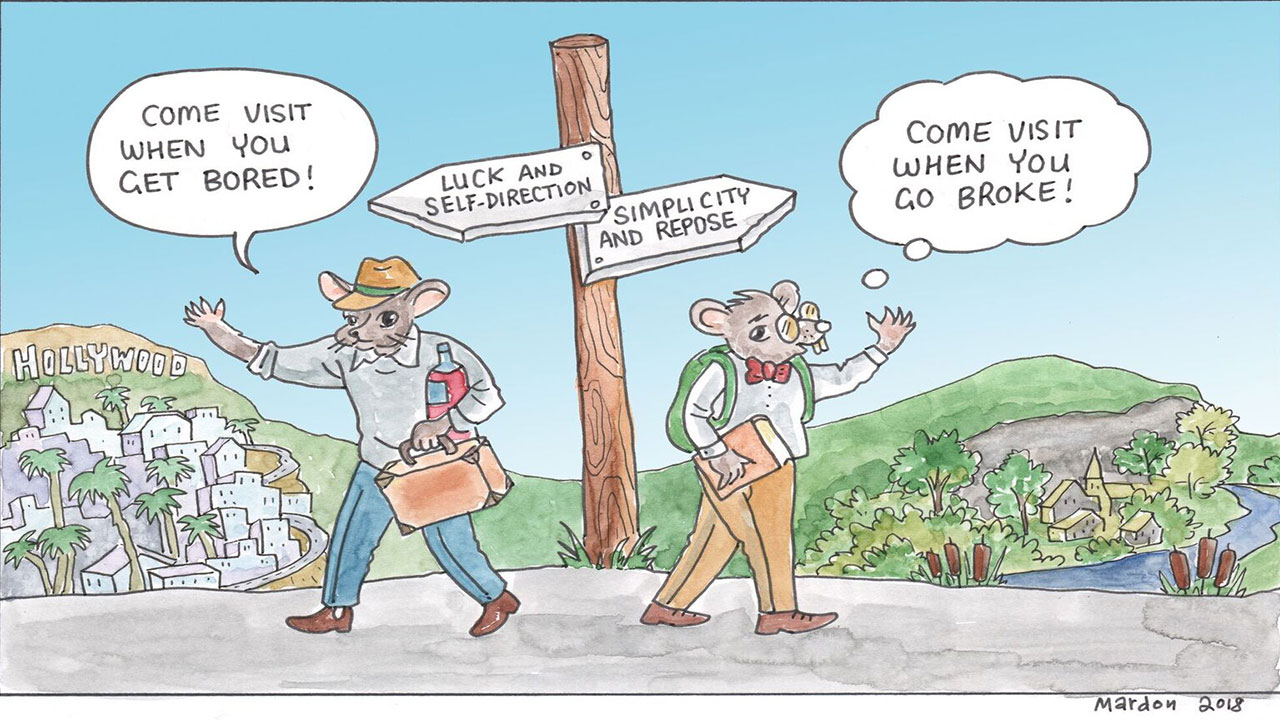

City Mouse, Country Mouse

A comparison of two ways of life that reflect national issues.

September 7, 2018

My friend Larry just moved to central Los Angeles from a suburb of Chicago. I would say he was following his dream, but he plans and works methodically toward goals, often for years, so there is little dreaminess in it.

Lately, I have been thinking about what I would want to do, and where, and how, once our kids are out of the house. In one possible future I might find a quieter place, get to see nature now and then, and find repose—yet do even more of the work important to me.

In taking interest in each other’s situations, Larry and I stumbled into a comparison of two ways of life that reflect national issues such as affordable housing, urban-rural splits, and political division.

Some background data for a thought experiment on how well we each might live, given our interests and decisions to this point

Larry and I met years ago in the cubicle-pen of a Fortune-1000 company. Looking back, our separate paths through jobs and geographies now seem to have meandering coherency—his ambition to be involved in acting and film, mine in writing and publishing.

Larry went on to be an IT manager at a big private university. He started acting again for the first time since college then started an online business to replace the IT job because it gave him greater flexibility to audition. He has acted on stage, in several commercials, and in a small number of TV dramas and history programs. He has agents in Chicago. He acknowledges all this makes him different from the stereotypical struggling actor moving to LA with no resources or contacts. He and his girlfriend are childless.

In taking interest in each other’s situations, Larry and I stumbled into a comparison of two ways of life that reflect national issues such as affordable housing, urban-rural splits, and political division.

I am married, have two sons, and have long worked as a teacher, writer, and editor. I own a house in a city of 75,000 and still go to campus for my job. But I am assuming I could earn a living remotely, which is fundamental to the plan.

Fudging the data

Because schools are often the deciding factor for families’ lifestyles, and because the cost of raising a child is so significant—nearly $250,000 from birth to age 17, the USDA says —I will pretend my kids are already out of the house. The only alternative would be to invent two for Larry, but he says he is not ready for kids, even hypothetical ones. (They would likely make his plan unworkable.)

Similarly, I will leave out information for partners, this time because the difficulty of finding adequate work for two in a small-town idyll would be worse than anything Larry and his girlfriend might face in a city of 4 million. Despite last year’s Gallup poll that showed 31 percent of Americans work remotely 80-100 percent of the time, I do not know a couple who does.

Finally, Larry and I are not interested in the extremes of our chosen models. He says he would not live in London, NYC, or Atlanta, even if one of those film centers was better for his acting career. Nor would he move to Louisville, Kentucky, for his online business’s sake, simply because it is a central air hub for UPS. For my part, I do not want some Kaczynskian shack off the grid; hot showers, lamplight, refrigeration, and the option of medical care are important to me.

One way of looking at the difference in lifestyles

Ecologist Howard Odum had a concept he called “transformities,” which “reveal the amount of energy embodied in things central to the well-being of human societies.” Sunlight shining on a field is Odum’s base measure, a “1” on his scale. Producing food, which concentrates energy for our use, is 100,000 on his scale. “Information” is 1 x 10 to the eleventh power.

How deep in “transformities” are Larry and I mired? We both have chosen professions high on the pyramid. Call them information industries, since we do not produce commodities such as coal or provide services such as purifying the city water supply. (This is why artists and some academics get testy when asked to justify their worth to society in this our age of budget cuts.) What is interesting is how the framework supporting each choice has its own demands and rewards. To do what you hope to do means participating in those other systemic demands—to be further mired, if that is how you view it.

As with most things, systemic demands are often symbolized by money. So what will Larry and I each pay, and what will be the texture of our experiences?

Larry does not view it that way, but I sometimes try to glance at the true bottom line of my activities. The framework of my lifestyle could be reduced in size and complexity, but his choices demand his participation in more systems—a massive city’s worth. I tried to explain to him he will benefit from the transformities and enjoy many of them, but he is mired.

He considered. “You won’t benefit from anything except the ‘1’ shining outside your window,” he said.

“I will have achieved repose,” I said. “Maybe even transcendence. So the ‘1’ will be perfect for me.”

He snickered. “In my ideal world I would have someone to suck out the pomegranate seeds from the dodecahedron, so I will always have a bowl full of perfect seeds with no pith. That’s what I want. I might let you watch when I order my assistant to do that task.”

As with most things, systemic demands are often symbolized by money.

So what will Larry and I each pay, and what will be the texture of our experiences?

Housing

The very reason for being of Larry’s move was to live in the biggest acting market in the country, which doubles his chances of being cast over those in Chicago. (California had six times more employment for actors than Illinois in 2017, but there are more aspiring actors.

Larry is a sybarite—he orders three entrees at a restaurant so he can sample them all, which he knows drives me nuts—and he never intended to suffer in the move. But it is common knowledge that housing prices in LA have skyrocketed. The LA Times reports that “the California median home price has risen to $529,900, a compounded annual growth rate of nearly 10 percent, according to real estate website Zillow. The median rent for a vacant apartment jumped an annual rate of nearly 5.5 percent to $2,426.”

Forbes listed LA as the city “Worst for Renters in 2018” , based on rent being two-thirds higher than the national average and 41 percent of local median income. Some businesses there cannot attract employees because they could not afford to live near their work. Commutes from cheaper housing are 90 minutes in areas of Greater LA.

Larry found a 700-square foot, two-bed, one-bath apartment in Larchmont Village, next to Koreatown, for $2,200 per month. New acquaintances are jealous of his great deal.

Larry found a 700-square foot, two-bed, one-bath apartment in Larchmont Village, next to Koreatown, for $2,200 per month. New acquaintances are jealous of his great deal. He already found a farmer’s market he likes, a spa, a bookstore, and the closest Astro Burger, where he ordered three entrees and several sides just to goad me. The neighborhood is near Paramount and the Hollywood Forever Cemetery, so his career is covered either way. But he did have to buy his own air conditioner, and then another, and then another, and he pays for utilities, a large storage unit for his business (none are climate-controlled), and monthly parking.

I like older homes with good lines and solid construction. Our previous house was an Italianate on the National Register, built in 1871. Sometimes before sleep I imagine a smaller (say, 1,000-square foot) house of this sort filled with books, plants, and natural light. I would like it to be in a small town that was an actual going concern—neither tourist trap nor blight—with basic amenities such as a grocery store in walking distance and a library.

We once passed through Grafton, Illinois, population 674, which sits above St. Louis at the confluence of the Mississippi and Illinois Rivers, so I will use that for my example. I have always loved a good river town. I could as easily choose Elizabethtown, Illinois, on the Ohio River; Marlinton, West Virginia, on the Greenbrier; or many others with charm and at least the appearance of infrastructure.

I could as easily choose Elizabethtown, Illinois, on the Ohio River; Marlinton, West Virginia, on the Greenbrier; or many others with charm and at least the appearance of infrastructure.

Zillow lists a perfectly nice 1,470-square foot Craftsman in Grafton, with river view, for $137,000. They estimate the mortgage at $414 a month. It has four beds, one bath, a deck, and detached garage. The realtor says it is turnkey. I will pretend that is true, and that it does not flood to the transoms, that the small waterpark and guest houses in town do not indicate cheap tourism, and that somewhere between the Hawg Pit BBQ and Grafton Fudge and Ice Cream I can buy groceries. St. Louis is an hour away, if I really want an indie film in a theater or Seoul Taco.

Housing results

Larry gets culture on the spot; I get peace and repose.

His rent and some expenses (I will use necessary parking and storage below) come to $2,600 per month.

My mortgage, insurance, utilities, and taxes will be about $800 per month.

Using the measure that housing should be no more than 28 percent of gross income, at this stage of the discussion Larry must earn (without accounting for any other debt, expenses [including medical insurance if self-employed], or savings) $111,429 per year. I need less than a third of that, $34,286.

Transportation

Larry will be hustling to curry favor with agents and casting directors. (“Just poking my head in,” he will say as he brings them bottles of premeditated wine.) He will be auditioning and running constantly to storage and the post office for his own business.

There is public transport in LA, but Larry is not a bus-stop kind of guy, especially carrying packages for customers or dressed for an audition. He does not like the expense of taxis and ride-hailers such as Uber and Lyft. He is interested in pay-and-drop scooters offered by startups such as Bird Rides and Lime, which went so crazy with them that Santa Monica, West Hollywood, and Beverly Hills have already banned the scooters and fined one of the companies, but those would be only for micro-local use, say to grab dinner.

Larry gets culture on the spot; I get peace and repose.

So, despite being in the thick of things, Larry will drive if he wants to conduct business, go to the beach, visit a museum, or do just about anything else more than three blocks from his apartment. Gas (a dollar more a gallon), insurance (a third higher), and maintenance in city driving are more expensive, and his car will wear out sooner and need to be replaced. He pays for parking ($250 per month).

My car, on the other hand, will sit in the driveway most days, and I would hope to walk the hills and the bank of the river.

Transportation results

Larry’s monthly costs could be $500, four(?) times more than mine.

Food

Larry loves it. You should see him chew. But he and his girlfriend rarely cook. They have tried an ingredients-in-a-box service, which averages about $11 per person per meal, but mostly they eat out (very expensive) or get delivery from places like Grub Hub ($20 per person per meal) with seemingly unlimited variety. They also buy a few groceries and get them delivered with services like Postmates.

“Last night I had a craving for ice cream,” Larry explained to me patiently. “I ordered three tubs, because there’s a minimum delivery charge, and it was 50 bucks. It was ten at night. God, it was good ice cream.”

I love food too. I cook all our meals and sometimes think of it as a way to be present and engaged in a process with metaphorical value. In Grafton I suspect I will not find lemongrass for pho at the grocery, but there is always the internet. I should not have to stoop to Thoreau’s fancy that he could eat grass if it would simplify, simplify. Pasta with sun-dried tomatoes, broccoli, garlic, and Parmesan is cents per serving.

Food results

Larry spends $1,500 per month on his food. I spend $225.

The cost of doing business

It takes money to make money as they say, and Larry has to keep up appearances just to be an actor: Mix-and-match outfits from Men’s Wearhouse, a second wardrobe worn only to auditions, professional haircuts, creams and unguents, headshots every two years ($600 a session), acting classes, acting showcases, video gear and mikes for audition taping, video production of his reel, website hosting, etc. He estimates he spends $400-500 per month on acting.

For his own business, which keeps him afloat, there is inventory purchase, storage, packing and framing supplies, postage, internet services and site listings. He estimates spending $65,000 per year on it.

But while his expenses are large (to me), profit can be great. He did a one-day commercial shoot for a knee-pain medical technology and got paid $12,000. Depending on other uses of his image, and residuals, gigs can continue to pay over time. His own business pays him 225 percent of what I earn.

I work on a six-year-old laptop, which will need to be replaced one day, and need an internet connection. In the past I have traveled and had other expenses. But generally, my work requires little outlay in return for modest and predictable pay. Call it $200 per month.

Health and quality of life

Larry is doubly blessed—first in being able to imagine a desired future, then in having opportunities to use his talents and will to bring it about. That kind of good luck and self-direction is relatively rare, it seems to me, and is therefore priceless. Then there is the vibrant, multicultural interest of his urban county, where “[o]nly about a quarter of the population is U.S.-born, non-Hispanic white,” and he can enjoy the sunshine and nights at the Roxy if he wants.

But LA is the most polluted city in the nation for the nineteenth year in a row. The American Thoracic Society and NYU did a study in 2011-2013 that showed an estimated 1,371 people died each year from poor air quality in the LA-Long Beach-Glendale area, number-one among cities in the study. The researchers call their numbers conservative and did not include longer-acting diseases such as cancer. The greater NYC area had 282 such deaths per year.

Even Larry admits he would live elsewhere, such as Santa Fe, if acting was not the thing. But he wants me to know, in his first month after the move, that he is happy. Happy.

Traffic, noise, glare, heat, stink, overcrowding, lack of privacy, homelessness, drugs, crime: Even Larry admits he would live elsewhere, such as Santa Fe, if acting was not the thing. But he wants me to know, in his first month after the move, that he is happy. Happy.

And I am happy for him. But look, I been around and have tried some things. At this point in my life I most value relationships; the best thought and feeling humans have produced; the natural world; alternations between world and sanctum; and time to appreciate them all. The rest has begun to slide away—what Thoreau was really getting at with his “simplicity” and all the “things [we] can afford to let alone.”

“Y’know, somebody laid down this rule that everybody’s gotta do something, they gotta be something,” Mickey Rourke slurs in his role as poet Charles Bukowski. “Sometimes I just get tired of thinking of all the things that I don’t wanna do. All the things that I don’t wanna be.” The prospect of Larry’s life makes me feel that way.

Health and quality of life results

I guess it is possible Larry will mount a security cam over his back door and spend his days watching strangers in a Rear-Window froth, but I doubt it. As long as his business continues to do well, and he gets traction with his acting, I think he will continue to be very happy in LA.

As for me, contemplating among houseplants, I suppose there might be a risk of isolation or boredom, but I doubt it. I can always visit Larry. Meanwhile the river rolls.

Total figures

Larry spends $205,829 per year for the privilege of exercising his will. I spend $40,886.

Larry says I underestimate all around, which is what he found on the web when he searched for information before his move. He is right. One of the costs of doing business, for instance, is getting there in the first place. For me, there would be a moving truck I would pack myself, closing costs, utility hookup, etc. He estimates his move cost him $15,000-$20,000, and original expenses for acting in a new context, which he compares to moving a business to a new location, might run another $5,000. This, he believes, is why young people who have a month’s rent saved for a shared LA apartment, in hopes of being discovered quickly, are doomed to return home. There is no data available for how many return from Grafton.

So?

Our chosen lifestyles reflect several national trends and problems.

First is the move to the cities. You have no doubt seen the maps that show the 39 metro areas that contain half the U.S. population, or the 23 urban areas that account for half the national GDP.

“In fact, 72 percent of [the] United States is classed as ‘rural’ area. That majority of the land mass holds only 15 percent of the population,” NPR reported in 2014. Not only do young people move away from rural areas where they grew up, but also retirees move in search of more comfortable places. Cities are growing, and rural populations are not just static but in some cases falling.

At this point in my life I most value relationships; the best thought and feeling humans have produced; the natural world; alternations between world and sanctum; and time to appreciate them all. The rest has begun to slide away …

As might be expected, opportunities, resources, and wealth cluster in the cities. “The size of the Los Angeles economy ($765 billion) in 2012 was larger than the GDP of both Saudi Arabia ($711 billion) and Switzerland ($631 billion),” the American Enterprise Institute says.

And this, some say, is one reason division hardens in our time: Those who live in the great mass of America outside cities, Princeton sociologist Robert Wuthnow says, often “feel threatened if they perceive Washington’s interest being directed more toward urban areas than rural areas, or toward immigrants more than non-immigrants, or toward minority populations instead of the traditional white Anglo population.” (Predictably, LA County went for Clinton, 71 percent. Jersey County, Illinois, where Grafton is, went for Trump, 71 percent.)

That feeling of being threatened can turn laconic, tribal, defensive, and conservative in the sense of desirous of no further change. And that can become other things, such as fears of “outsiders” or those trying to “jump in line.”

It began to be apparent long ago that not everyone can earn a living in a small American town. My mother, a teacher with a master’s, tried to find work elsewhere than the little southern Illinois town where I grew up. She could not, so we stayed put. After years of unemployment and poverty she ended her working years on the line in a washing machine factory. (It has since gone out of business.) The costs of moving away from her remaining family to, say, Chicago required first of all certain employment, and second the kind of bankroll for moving costs, rent, security deposit, etc., that Larry points out—none of which she could find. She and I were left behind, in a sense, for living not only where she preferred, but where we had to. It is an odd dilemma, and ruinous.

Larry and I can explore our wishes, but for most people now the issues we have been discussing have nothing to do with aesthetics or choice.