Do The Right Thing

A new book enlightens the conservative ideal for African-Americans, but fails to inspire

By Gerald Early

February 12, 2015

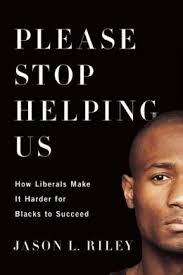

Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to Succeed

A conservative website dedicated to exposing what it perceives as the irrational radicalism of the left, Progressives Today, has a headline, “Shock Video>>>Black Conservatives Met with Hostility, Harassed at Annual NAACP Convention.” The video shows a member of the NAACP, self-identified as Adrienne Jones, asking Deneen Borelli, author of Blacklash: How Obama and the Left Are Driving Americans to the Government Plantation (2012), a leading black conservative and minority outreach director of FreedomWorks, why Borelli would want to be at the NAACP convention when she is opposed to the values of the organization.

I thought that Ms. Jones got the best of the argument. After all, Borelli admits that she is not a member of the NAACP. So, as Ms. Jones reasons, why should an organization to which you do not belong, and that indeed you ideologically oppose, permit you to speak at its convention? Black and white conservatives have tried to frame this as the NAACP shutting down free speech and the free exchange of ideas in the black community. But the NAACP does not owe its critics a platform any more so than the conservative National Review, for instance, which does not invite members of the NAACP to speak at its cruise conventions. Why should they? When the Democrats hold their national convention, they don’t invite Republicans to offer opposing points of view. Ms. Jones suggests that black conservatives hold their own convention, which seems a perfectly sensible idea. Why don’t they?

The answer might be that black conservatives and their white allies would much rather exploit the idea that they are sacrificial lambs in black community, victims of the “race grievance” and “civil rights” crowd who foreclose their ability to reach the black masses with their ideas, that these leftist black factions fear the spread of black conservatism, assuming that once everyday blacks hear this perspective uncensored the scales will fall from their eyes and wisdom will descend; and so the lefties shut these viewpoints down. Thus, in conservative eyes, the black community is presented as narrow-minded and ideologically imprisoned, trapped on the “plantation,” (conservatives’ favorite word in this regard), of white liberalism and leftist thought. This is an interesting tactical approach for conservatives to take concerning African-Americans because it seems so obviously doomed, if the aim is to get blacks to change their political orientation.

Conservatives have used black censorship as an excuse for why they have failed to offer African-Americans a viable, competitive alternative to Democrats and the left. Historically, conservatives have ceded blacks to liberals and the left, and now, feeling the social pressures of the multiculturalism they deride, they wish to complain that blacks show little interest in conservatism, in fact, frequently despise it. Moreover, with this approach, conservatives are asking African-Americans to accept a hugely unflattering view of themselves as politically misled by the left and crippled with a dysfunctional culture as a major step toward self-awareness and political truth. It is certainly not impossible to win a political constituency with this sort of “tough love” or “afflicted with false consciousness” tactic, but it is truly impossible for conservatives to do so with African-Americans because, on the whole, blacks will never be convinced that white conservatives have their best interest at heart or see blacks as anything other than a social mistake and a political nuisance. Nonetheless, conservatism is something that blacks should take more seriously, if only to grant themselves more leverage and to vary aspects of their criticism of liberalism and the left. After all, nearly 37 percent of blacks describe themselves as conservative, a greater percentage than those who describe themselves as liberal.

Jason Riley, black conservative editorial writer for the Wall Street Journal, writes in his new book, Please Stop Helping Us: How Liberals Make It Harder for Blacks to Succeed, “Blacks have become their own worst enemy …” Many African-Americans will find this off-putting, coming from a black conservative; yet many blacks, from David Walker to Malcolm X to Marcus Garvey to Louis Farrakhan to E. Franklin Frazier have expressed similar sentiments: self-correction is a form of discipline and agency. Stop acting against your own best interest! This sort of message has an enormous appeal to members of a persecuted minority, if it comes from the right person.

To be sure, African-Americans have always believed in self-reliance, have always distrusted white liberals with their missionary, paternalistic zeal, and were often suspicious of white and black radicals who, acting as revolutionary hammers “in the struggle,” reduce everything around themselves to nails, including blacks. So, it is not as though the overall message of Riley’s book would be completely unacceptable or unappealing to blacks. Stop allowing white liberals and leftists to treat you as a guinea pig or a charity case or a club with which to beat white conservatives! Riley is nobody’s black nationalist, but some of the sentiment here is similar to militant black nationalism, which possesses strong elements of conservatism. If nothing else, his book might serve as a good complement and contrast to Silent Racism: How Well-Meaning White People Perpetuate the Racial Divide (2006) by Barbara Trepagnier, the leftist attack on white liberal attitudes by, well, a well-meaning white person.

Riley’s book, if anything, tries to create a modern black conservative intellectual tradition, dedicated as it is to Shelby Steele, English professor and public intellectual, and Thomas Sowell, economist and public intellectual, the two most well-known and arguably influential black conservatives on the scene today. Supreme Court justice Clarence Thomas, a roundly disliked black conservative, gets his “props” too.

This book, smoothly written and concisely argued, recites the standard black conservative views: liberal government programs and policies of the 1960s, including Affirmative Action, have harmed blacks immeasurably and explain the problems of blacks today; that crime, not incarceration, has destroyed black communities; that even many middle-class African-Americans are anti-intellectual and do not properly value education; that African-Americans are afflicted with a popular culture that underscores and reinforces the negative aspects of black communal life; that the minimum wage and unions work against the economic interests of blacks; that charter schools have helped African-Americans greatly.

In a way, Riley’s book is of a piece with Chika Onyeani’s far more provocative and controversial Capitalist Nigger: The Road to Success, A Spider Web Doctrine (2000), which argues that blacks becoming a moral protest flank in the American leftist army (“the blame game”) have made them useless to themselves: “The blame game has become a permanent part of our lives to the exclusion of any other solution that could be more viable in solving our problems. It has become the most productive part of our lives, because without it the African cannot really point to much that they are in charge of producing. It is better to blame others than to confront the truth of our being responsible for whatever has happened to us as an African race.” (Capitalist Nigger) Riley would doubtless say amen to that. In fact, I suspect many blacks would agree with Onyeani’s perspective, as it taps a vein of self-respect and race pride. Most blacks, without question, would rather be successful capitalists, however “exploitative” of land and labor, than wards in an egalitarian socialist state because, in the end, even members of a persecuted group, the dream is to have power, not justice. Or put another way, the acquisition of power becomes its own form of justice. The problem with Riley’s book is not its conservative message, but that the message is not sufficiently framed to appeal to black folk’s sense of racial destiny and pride. In short, it is insufficiently chauvinistic, less chauvinistic than the title promises.

Like all polemics, Riley’s book affirms the converted but is not likely to win many new converts. Nonetheless, the work is lively, intelligent, and gives an interesting perspective of black life, and, so, is worth a read, if only as a note of diversity in our common understanding of black intellectual thought.