Tourist Street With a Backbeat

Bourbon Street is a welcome addition to—and intervention in—New Orleans cultural and geographical history.

January 13, 2016

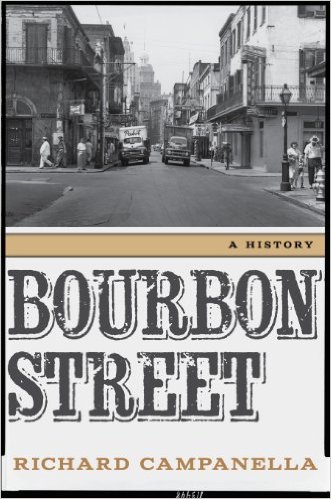

Bourbon Street: A History

New Orleans suffers no shortage of academic and intellectual study of its complex history and culture. One might even say that it is a hotspot for studying the contradictory spaces of American culture. The city lends itself to rich histories of urbanization, immigration, tourism, race, class, gender, and sexuality, just to name a handful. And yet, where might we locate the infamous Bourbon Street—perhaps the most visited street in the United States for nearly a century—in those histories? To be sure, we have the occasional, brief academic study, but no sustained, book-length project on the rich strip from Canal Street to Esplanade Avenue. How has a street so alive in the popular imaginary—as evidenced in an enormous archive of literary, filmic, musical, and touristic representations—been rendered so dead to academic engagement?

Enter Richard Campanella’s recent Bourbon Street: A History, a welcome addition to—and intervention in—New Orleans cultural and geographical history. Campanella’s book asks these questions, and more often than not, convincingly answers them. Early in his preface, Campanella suggests, “The [academic] oversight is not an accident; it’s an acerbic snub and a contemptuous dismissal. The most that ‘serious’ researchers usually allot to Bourbon Street is a patronizing reminder to their audience that it does not represent ‘authentic’ New Orleans, and that such amateurish delusions must be set aside before the forthcoming cultural enlightenment may commence.” Campanella’s assessment is on point, and the notion that there might exist an “authentic” anything should raise eyebrows; however, upon first reading, I wondered whether his defensive—indeed, at times seemingly angry—position might lead him to leave unexplored the darker, less celebrate-able sides of the Street.

For the majority of the book, Campanella’s serious consideration of multiple angles, both at the level of perspective and of scope, abated this concern. As a cultural geographer, he is well attuned to the ways in which space shapes and is shaped and reshaped not only by government authorities and city planners, but by the many people who live, work, and play on Bourbon Street, people whose own histories and understandings of the Street varied widely. Campanella’s history is a richly textured one, attempting to account for the ways in which the intersectional identities of race, ethnicity, class, gender, and sexuality do real imaginative work on the space of a single street.

Campanella reminds us that, even as we critique concepts like “authenticity,” our cultural biases might still shape our topics and our arguments about them. Bourbon Street asks us to think about and to take seriously “inauthentic” space, to ask what it might tell us about our cultures and our histories.

Bourbon Street’s history begins in 1682 when René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle claimed for France the wilderness that would later be named New Orleans, and the book ends in the present day (actually, it begins rather grandly, a little unnecessarily, 18,000 years ago). As is probably clear here, Bourbon Street covers a broad sweep of history. This sweep has its costs and its benefits. One cost is that the entire first section of the book, which traces the years 1682 to 1860, feels hurried. While Campanella claims that “[few] eye witnesses who recorded accounts of eighteenth-century New Orleans found anything particularly salient on Rue Bourbon,” and that “[it] was pedestrian, unpretentious, and utterly unexceptional,” this unexceptionality leads him to write a brief, roughly 70 page, history of New Orleans more broadly, and the French Quarter more specifically. As the book’s first section focuses more sharply on Bourbon Street, Campanella reiterates just how typical of the French Quarter it was with regards to ethnic, racial, class, and caste demographics. He also reiterates that, until the mid-19th century, Bourbon Street exhibited little that might make it “special” or even notable, little that might resemble the Street today.

The result of this is a history that feels too broad, and thus often spotty—an obligatory antecedent to the much longer and more richly detailed second section, which covers the 1860s to the present. Here, Campanella accounts for topics as varied as the politics of race and proximity around the time of the Civil War; transient soldiers in World War I and World War II who experienced the Street and “brought it back home” and made the Bourbon Street tourism industry boom; prostitutes who maneuvered through political and interpersonal landscapes; how the presence of jazz on the Street diminished over decades; how gay and lesbian communities carved out “queer space” across the “Lavender Line” of St. Ann Street; how preservationists shaped the Street in their image … the list goes on. What emerges in these seemingly disparate narratives is not a sense of cohesiveness; instead, Bourbon Street: A History takes a single street as its focus to reveal the multiple overlaps and interrelations of different cultures and different histories. Again, though, this method has its costs, at times exchanging topical breadth for depth. The book’s chapter that covers the late 1940s to the early 1960s is exemplary in this regard. It is divided by paragraphs that begin with rhetorical questions, “Lewdness on Bourbon Street?”, “Bibulous indulgence on Bourbon Street?”, “Sex on Bourbon?”, “Vulgarity and tastelessness on Bourbon?”, and so on, with each topic receiving as much space as a few pages and as little as a couple of paragraphs. These are the topics of entire book-length projects in themselves. And as book projects, they would demand a more critical historicization of the terms Campanella employs.

As the second section continues, and as Bourbon Street becomes more recognizable as the Bourbon Street “we know today”—from the 1980s to the present—the book takes on less of a loose topical structure and instead proposes some rather straightforward historical arguments. The first, which seems suspect, is that Bourbon Street is relatively unchanged since the 1980s: it is the same well-oiled machine with the same touristic tropes and traps. Campanella’s second major argument appears in the third section of the book, “Bourbon Street as a Cultural Artifact.” He argues that the scholarly revilement directed toward Bourbon Street implicitly reveals the assumptions of scholars and tourists alike as to what constitutes cultural “authenticity”: Bourbon Street, detractors would say, is an “inauthentic” street-long cultural wasteland in the midst of perhaps the representative city of “authenticity.” Campanella cheekily ventriloquizes, “New Orleans … had history, culture, and the poignancy of tragedy and past grandeur. It had a European look, a Caribbean feel, an expatriated vibe, an abundance of historic housing at low rent, a pervasive booziness, and music, food, and festivity to boot. It was authentic!” Campanella eloquently and forcefully debunks myths of authenticity and reveals the race- and class-based histories and the biases that inform, drive, and sustain these myths. This argument about authenticity threads through each chapter in this final section, whether he discusses the relationship between space and economics, space and “coolness” (in which he includes maps of “cool” and “uncool” neighborhoods in and around the French Quarter), or what he sees as Bourbon Street’s heroic status in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. As these topics suggest, the book’s last section is also its most idiosyncratic; chapters feel less like historical narratives than essays about contemporary culture. For scholars who have long been wary of the concept of “authenticity,” Campanella’s argument might seem outdated. But his argument in the preface bears repeating: Bourbon Street has never had its own sustained historical study. He reminds us that, even as we critique concepts like “authenticity,” our cultural biases might still shape our topics and our arguments about them. Bourbon Street asks us to think about and to take seriously “inauthentic” space, to ask what it might tell us about our cultures and our histories.

But Bourbon Street: A History is not a book written only for historians; rather, it transcends the line between “academic” and “popular” style. This is one of the book’s major triumphs. It bursts with rich, accessible prose: while at one moment Campanella invites his readers to “stand at the intersection of Rue Bourbon and Rue Bienville in January 1732”, at another moment he eloquently personifies the Street in its contemporary form, arguing that it “does not indulge in tear-eyed nostalgia or effusive introspection; it makes zero claims to cultural exclusivity or authenticity, and offers absolutely no apologies.” I anticipate that Bourbon Street will garner interest not only from historians and other scholars in the humanities, but a wider audience as well. Campanella’s archives are as rich and idiosyncratic as Bourbon Street itself; his prose is both witty and inviting; his argument is forceful, lucid, and often convincing. And even if the book’s approach is often too broad in historical and topical scope, it is an important intervention in the study of New Orleans history and culture—and a welcome invitation for further inquiry into this extraordinary and still controversial Street.