Magical Autobiography Tour

"The Dersh" exasperates us with his self-regard, but enchants with style to burn

October 1, 2014

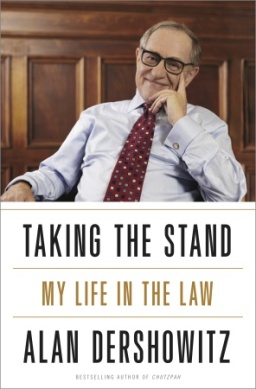

Taking the Stand: My Life In the Law

The term “autobiography” covers a wide range of expression. It includes the tale of redemption, as in Confessions, the title of two significant and significantly different salvation stories, one by St. Augustine and the other by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It also includes the enchanted time machine version that transports us back to a lost era, such as Vladimir Nabokov’s aristocratic childhood in pre-revolutionary Russia in Speak Memory and Annie Dillard’s Pittsburgh of the 1950s in An American Childhood. And the famous-people-I-have-known version, which in its Hollywood incarnation includes the charming and irresistible The Moon’s a Balloon by actor David Niven and the notorious and irresistible The Kid Stays in the Picture by producer Robert Evans. And the lessons-from-life version, which can be as epic as The Education of Henry Adams or as modest as A River Runs Through It. And the I-fought-the-law-and-the-law-lost tales of courtroom glory, such as Clarence Darrow’s The Story of My Life and Louis Nizer’s My Life in Court. And finally, alas, the boaster’s version—the literary equivalent of being trapped in a window seat in coach next to a windbag who views the two-hour flight as the perfect opportunity to “regale” you with tales of his totally awesome genius and importance.

Whatever your preferences or dislikes in autobiographers, Alan Dershowitz includes them all in Taking the Stand. Depending upon the chapter, you will be enchanted, enlightened, or exasperated. Ultimately, your enchantment and enlightenment will outweigh your exasperation. I promise.

Taking the Stand is divided into four sections. Part I, entitled “From Brooklyn to Cambridge,” fits within the traditional autobiographical structure, taking us from the author’s childhood in New York City to his young adulthood as a professor at Harvard Law School. Part I features some of the most delightful and exasperating portions of the book. The opening chapter transports us back to the 1940s and 1950s of Boro Park, the Orthodox Jewish neighborhood in Brooklyn were Dershowitz grew up. This is my favorite chapter of the book. It’s filled with wonderful scenes at home with his family, in his yeshiva, in his neighborhood, and in the Borscht Belt in the Catskill Mountains, where he worked as a busboy and honed his keen sense of humor, displayed throughout the book.

This is where you will find yourself wedged into that window seat in coach while the persona the author dubs “the Dersh” reminds you—on almost every page—how totally amazing he is. And not just his brains.

The remaining chapters of Part I chart his impressive path from Brooklyn College to Yale Law School to prestigious judicial clerkships to his early years at Harvard Law School. This is where you will find yourself wedged into that window seat in coach while the persona the author dubs “the Dersh” reminds you—on almost every page—how totally amazing he is. And not just his brains. The Knights, his sports club at Brooklyn College, won the school’s intramural soccer title. While not quite the World Cup, it provides him an opportunity to quote this headline from the school paper: “AL DERSHOWITZ LED THE KNIGHTERS TO VICTORY, SCORING TWO LARGE GOALS.”

He achieved an A average and Phi Beta Kappa at Brooklyn College, got into all the law schools he applied to, graduated first in his class at Yale Law School, got the highest grade on the bar exam, and so on and so on. By the time he turned down Harvard Law School for Yale, I went online to check on the audio version of this 510-page book and discovered that my whimsical two-hour-flight metaphor might actually be a 21½ hour slog to God knows where—and with no way off the plane, since I’d signed on to review the damn book. I felt like that character in the movie Airplane! identified in the cast list as simply “hanging woman.”

By the time I reached the end of Part I, where Dershowitz has become “the youngest assistant professor in the history of the law school of the greatest university in the world,” I was reminded of that Jerry Seinfeld riff about McDonald’s obsession with counting the number of hamburgers sold. “How insecure is this company? 40 million, 80 million, billion jillion . . . who cares? I’d like to tell the CEO of McDonald’s, ‘Look. We all get it, okay? You’ve sold a lot of hamburgers. Whatever the number is, just put up a sign: McDonald’s: We’re Doing Very Well.’”

And perhaps that’s what Dershowitz’s editor suggested, because Part II marks a shift from exasperation to enlightenment and enchantment as he takes the reader on an instructive and provocative tour of important and contentious realms of free speech, from the Pentagon Papers to WikiLeaks, with stops along the way for obscenity, privacy, Holocaust denial, and speech that supports terrorist groups. Part II provides a genuinely fascinating tutorial on the First Amendment guarantees of free speech—including even hate speech. Dershowitz’s commitment to the principals he defends remains strong even when he becomes the target. One such example, which he appends to a discussion of a case involving a truly vicious campaign ad, is when he was victimized by an nasty cartoon used to illustrate an article by “the notorious Israel-basher Norman Finkelstein.” The cartoon portrayed Dershowtiz watching a news story showing Israeli army soldiers killing Lebanese civilians:

[The cartoon] had me sitting in front of the television and masturbating in ecstasy over the civilian bodies strewn on the ground. Since I am clearly a public figure, and since this was plainly a parody, it was protected speech under the First Amendment. Sometimes being a First Amendment lawyer requires thick skin. (p.180)

His personal involvement in many of these First Amendment disputes adds a dash of spice to what is already a fascinating topic. This is true even when the free speech conflict is relatively minor, such as the academic spat engendered by the publication of a book on alien abductions by Dr. John Mack, a Harvard Medical School professor and psychiatrist. The book, Abduction: Human Encounters with Aliens, “recounted Dr. Mack’s treatment of numerous patients who had been referred to him after claiming that they had been abducted by space aliens.” Concluding that most of these patients exhibited symptoms of genuine trauma victims instead of mental illnesses that would produce delusions of abductions, he “refused to dismiss the possibility that his patients were accurately reporting what had happened to them.” (pp. 172-72.) Dr. Mack’s book became a bestseller and turned him into a talk show celebrity. Harvard was not thrilled. The dean of the medical school launched an investigation into what he labeled as Dr. Mack’s “astounding claims.” Dershowitz’s involvement in the controversy not only adds a dimension to the story but gives him an opportunity to raise issues you probably didn’t spot as you read the facts of the case. In the process, he will challenge your initial reactions to the dispute, just one of many examples in the book of why his students give him such stellar ratings (as he reminds you).

Criminal justice has been the main focus of Dershowitz’s academic career and his writings, both academic and popular. Thus it makes sense that the most substantial portion of his autobiography—Part III—is devoted to that subject. Despite the occasional jump cut to the Dersh on stage giving himself a thumbs-up, Part III is an absorbing and provocative collection of criminal law vignettes organized around important themes in due process, as evidenced by some of the chapter headings in this section of the book: “The Changing Politics of Rape: Mike Tyson, DSK, and Student Protests,” “The Death Penalty for Those Who Don’t Kill,” “Using Science, Law, Logic, and Experience to Disprove Murder: Von Bülow, Simpson, Sybers, Murphy, and MacDonald,” and “The Changing Impact of the Media on the Law: Bill Clinton and Woody Allen.”

In the chapter on rape, Dershowitz opens with a detailed and nuanced dissection of the rape charge for which Mike Tyson was convicted. The facts Dershowitz brings forth conflict in disturbing ways with the version offered by the media—so much so that Tyson himself becomes a victim, and maybe the only one. This chapter also includes an examination of several other high-profile rape defendants, including Dominique Strauss-Kahn (accused of forcing a hotel maid to perform oral sex on him), an elderly Chassidic man (accused of child molestation), and a group of doctors (accused of gang raping a nurse). In each of these cases, Dershowitz’s presents facts that undercut any claim of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Throughout much of the book, but especially in this Part III, Dershowitz includes scenes and sidebars featuring some of the famous people he has known or represented. His three encounters with billionaire Leona Helmsley (pp. 357-58), who he describes as “boring and rather stupid,” offer proof beyond a reasonable doubt that she deserved the title “Queen of Mean.” By contrast, the time he spent with former heavyweight boxing champion Mike Tyson in connection with Tyson’s rape case provides a sympathetic and nuanced view of a complex individual who was, in Dershowitz’s words, “a wonderful client, always polite, always honest, always honorable, and always thinking of others.” (pp. 326-27) Then there is Harry Reems, born Herbert Streicher, who became the infamous male lead in the X-rated Deep Throat. A college dropout and former marine, Reems describes himself to Dershowitz as “a nice Jewish boy earning his livelihood by doing what lots of people would pay to do.” (p. 132) And for those of us who enjoy a side of schadenfreude with their autobiographies, the Dersh’s methodical evisceration of what he views as superlawyer Robert Bennett’s bungling of Bill Clinton’s defense in the Paula Jones and Monica Lewinsky sex scandals (pp. 367-72) displays the chutzpah that has endeared Dershowitz to clients and outraged his adversaries.

In the Part IV, Dershowitz takes on three current fields of controversy: affirmative action, separation of Church and State, and international human rights. His treatment of these issues is passionate, informed, and challenging, as the subtitles of those chapters indicate: “From Color Blindness to Race-Specific Remedies”; “Attempts to Christianize America”; and “How the Left Hijacked the Human Rights Agenda.” Regardless of your views on these topics, Dershowitz’s provocative approach will engage your thoughts and challenge your opinions.

One such example is abortion. While asserting that he has “always supported a woman’s right to choose abortion,” he nevertheless argues that there is no constitutional basis for that right. Instead, he views the abortion issue as “quintessentially political,” contending that it involves “a clash of ideologies, even worldviews. Unlike issues of equality, the controversy over abortion has no absolute right and wrong side, either morally or constitutionally.” He walks the reader, point by point, through his argument that the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Roe v. Wade was not merely flawed but, ironically enough, “helped secure the presidency for Ronald Reagan” and planted “the seeds” of the Bush v. Gore, which he views as merely the opposite side “of the same currency of judicial activism in areas more appropriately left to the political process”:

Judges have no special competence, qualifications, or mandate to decide between equally compelling moral claims (as in the abortion controversy) or equally compelling political claims (counting ballots by hand or stopping the recount because the standard is ambiguous). Absent clear governing constitutional principles (which are not present in either case), these are precisely the sorts of issues that should be left to the rough-and-tumble of politics rather than the ipse dixit of five justices. (p. 415)

While one can pick away at some of the links in his chain of argument—indeed, even Dershowitz concedes that, unlike the five-Republican-majority in Bush v. Gore, no accusation of political partisanship taints Roe v. Wade—he is not alone in his views of the unintended harm caused by the abortion decision. Even Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, a longtime champion of women’s rights, has been harshly critical of the reasoning behind and the impact of Roe v. Wade.

The book ends, fittingly, with the reappearance of the Dersh in the form of—ready?—his letter to a future newspaper editor that he requests be published after his obituary has been published. His posthumous letter points out that in addition to all the high profile cases discussed in his obituary he wants to remind everyone that he handled lots of pro bono cases for indigent clients and did other wonderful things in his life. I sighed and thought of that passage from Book Four of the Meditations of Marcus Aurelius:

The man whose heart is palpating for fame after death does not reflect that out of all those who remember him every one will himself soon be dead also, and in the course of time the next generation after that, until in the end, after flaring and sinking by turns, the final spark of memory is quenched.

Then again, I reminded myself, Marcus Aurelius has been dead for nearly two millennia but his book remains in print and he landed a plum role in the movie Gladiator, where he’s played by Richard Harris. May the same be true for the Dersh. And until then, I hope that Taking the Stand will not be the last time Alan Dershowitz takes the stand in print. In the interim, though, he may want to heed Seinfeld’s advice and put up a sign on his front lawn: “The Dersh: I’m Doing Very Well.”