Charles J. Guiteau shot President James Garfield in the back on July 2, 1881. Today, the wound that Garfield suffered would likely not have killed him but unfortunately his team of doctors did not have x-rays and did not know about germ theory. They dug around for the bullet with unwashed hands and unsterilized instruments. Garfield managed to live for 79 more days, mostly in great distress and discomfort caused not only by his physicians but by the tremendous Washington heat. His bedroom, as was the White House itself, was nearly airless—as all the government buildings at the time were poorly ventilated—and Garfield sweated profusely, desperate for any sort of relief from the intense heat, temperatures frequently getting close to 100 degrees Fahrenheit. All sorts of methods were tried to cool his room: sheets were soaked with ice water and then air was blown through them, the oldest method of “air conditioning” known to mankind, which did not cool the room; cooling machines of various types, all using ice, were tried and all failed. At last, along came Simon Newcomb, a mathematician-astronomer, who did something no one thought of doing: measuring the room to figure out how much power and ice would be needed to successfully cool it; as a result, one of the machines was re-calibrated to cool room, lowering the temperature to the mid-70s. Or, let us say, the machine could have lowered the room’s temperature by as much as 20 degrees if Garfield had not insisted that the room’s windows had to remain open. Garfield, like most people of the period, and even many today, thought it was unhealthy to sleep in a room with closed windows. The temperature in the sick room never got below the mid-80s, as a result. The cooling machine was also expensive to use, consuming more than 400 pounds of ice every hour.

Garfield died of blood poisoning on September 19, but the public, which had anxiously followed the highly detailed daily updates of his treatment, was intrigued particularly by the attempts to cool his room. Despite the inefficiency of the machine that was used to cool Garfield’s room, the public was made aware that not only was such cooling possible but that it may provide healthful benefits to the ill and critically injured being treated in hospitals. It is hard to recover one’s health perspiring in an oppressive summer heat wave. Artificial cooling for comfort was not just a fantasy or a form of sinful, character-rotting indulgence, as many Americans believed at the time. Some uses of artificial cooling could be good, even necessary. This was a major step forward in the public perception of artificial cooling as most people, understanding that as it was so much easier to warm oneself in cold weather than to cool oneself in hot weather, were certain that it must be God’s intention for people to endure heat, that it was somehow unnatural to combat heat.

Americans were more fully aware that modern life, urban life in the late 19th century, made heat more unbearable than ever. As Salvatore Basile writes in Cool: How Air Conditioning Changed Everything: “America was realizing that a heat wave was much more unpleasant in cities than in rural areas: the larger the city, the more brick and stone and human bodies, the more hellishly hot it felt. And New York might be the nation’s largest, richest, and most cosmopolitan northern city, but in reality its latitude was more nearly equivalent to that of Madrid. … Visitors flocked to see Manhattan’s ‘skyscrapers’ … and were dismayed to find those looming buildings so badly designed and so closely packed together that breezes were rare and upper floors were like ovens. They trotted up and down Fifth Avenue, gawking at the sumptuous mansions of the wealthy; had they permitted to enter, they would have found the air inside those homes as hot, heavy, and oppressive as the atmosphere inside any slum tenement.” In short, modernist architecture, the rise of heat-producing industrial machinery from the internal combustion engine to the camera, and the geographical compression of urban populations, the sort of transformations that was changing the nature of experience itself, made a sort of climate change in the 19th century, intensifying the experience of heat in ways that people had not imagined before. A man-made heat was being created that could only be controlled, ultimately, by man-made cooling. Slowly, inchoately, but tenaciously, the quest for coolth had begun. One year before Garfield’s assassination, Madison Square Theater in New York became the first to be air-cooled, and thus the first to be able to stay open in the summer.

… as it was so much easier to warm oneself in cold weather than to cool oneself in hot weather, the public was certain it must be God’s intention for people to endure heat, that it was somehow unnatural to combat heat.

The conditions created by the heat that made Garfield’s struggle so much more agonizing than it had to be convinced many people that artificial cooling could be practical and moral. The death of Garfield, as Basile recounts it, is just one more 19th century prefiguring narrative of how the United States moved toward becoming in the 20th century the Nation of Coolth, the most air-conditioned country in the world. Incidentally, the White House was not air conditioned until the Truman administration, when the building was so dilapidated and structurally unsound that it had to undergo three years of massive renovation.

The path of air conditioning was never smooth. Even by the early 20th century, two decades after the death of Garfield, it was wracked with problems. “Yes, chilling milk in a warehouse with machine-made cold had become common-place,” writes Basile, “But trying to cool a room had proven to be impractical, ridiculously expensive, and error-prone …” Coolth was the term used for cold air blown from a machine, coined by an engineer with a sense of humor and a knowledge of Old English before engineer Willis Carrier, the father of modern air cooling, came up with the more scientific and modernist term “air conditioning.” The change in terminology was part of the transition from 19th century small-shop tinkering to 20th century Big Science.

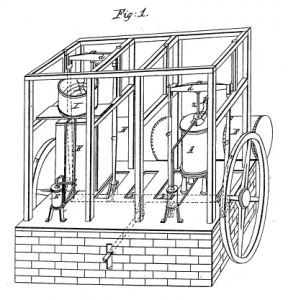

The first step to Willis Carrier and modern air conditioning was human beings learning how to manufacture ice with a machine. So, in many respects, as Basile notes, John Gorrie, a physician from Florida who was interested in making a device that could lower body temperature and thus help his swampland patients afflicted with fever, is the real father of the coolth with his cooling machine patented in 1851, which could not only lower the temperature of a room but could also produce ice: “[He] laid the groundwork for practical mechanical cooling,” Basile states. Unlike others who had fooled around with the idea of making ice, “John Gorrie had actually produced a machine that was complete. More important, it worked. For the first time, a machine was manufacturing cold air.” Gorrie thought, rightly, that if cooling a room was not seen as very important by the public that being able to make ice would be boon to medicine. Unfortunately, he was ahead of his time and his ice-making machine was not only unappreciated by the public; it was not believed to be true because the machine used steam to produce ice, which most people thought was impossible. Gorrie died in 1855 in obscurity, unable to get financial backing to mass produce the machine.

John Gorrie’s famous, but also famously unfunded, ice machine: “For the first time, a machine was manufacturing cold air.”

Once science conquered ice-making, refrigeration became a reality. Without perfecting refrigeration, air conditioning would not have been possible. What drove the public’s desire for air conditioning in the 20th century was mass entertainment and mass consumption. The Broadway theater crowd might have been willing to endure hot, stuffy theaters longer than they needed to but not the masses who attended movies. Quickly, movie theater operators discovered that air conditioning made watching films a far more tolerable experience for audiences and far more lucrative for themselves. Movie audiences so longed air conditioning that theater operators discovered that the equipment installation paid for itself in a matter of a few months, no matter how expensive the costs. The modern office building also drove the need for air conditioning, as they were usually built with lots of glass and windows that did not open, making for poor ventilation and lots of internal heat. Without air conditioning, as Basile asserts, “many of the world’s buildings would be completely unventilated, and hence uninhabitable.” Radio stations, color film sets, and television studios—all of which tended to be infernos—had to be air conditioned if the performers were expected to live and perform another day. Department stores also had to have air conditioning for the comfort of their middle-class and upper-middle-class women patrons. With air conditioning’s creeping ubiquity in public spaces, there was little to stop it, after World War II, from conquering its final two frontiers: the private residence and the automobile. By 2014, as Basile points out, nearly 90 percent of American homes and 98 percent of cars in America have air conditioning.

Coolth was the term used for cold air blown from a machine, coined by an engineer with a sense of humor and a knowledge of Old English before engineer Willis Carrier came up with the more scientific and modernist term “air conditioning.” The change in terminology was part of the transition from 19th century small-shop tinkering to 20th century Big Science.

Air conditioning has its critics, even its enemies. There is no question that the spread of it has greatly strained American power capacity (as well as the power capacity of other countries where it is becoming increasingly popular), leading to blackouts, brownouts, and more costly energy. Air conditioners have become more efficient over the years but they are still big eaters of electricity. They also produce a great deal of heat which may have contributed to global warming and which, ironically, encourages the public to use air conditioning all the more to fight the growing heat. Environmentalists have accused air conditioning of not only being a big drain on energy but also of damaging the atmosphere. Freon, the miracle non-inflammable gas that fueled air conditioners, was discovered to have damaged the ozone. It has been outlawed by easy stages. Replacement gases have not been a big improvement and so we might all return to the original air conditioning gas, ammonia. Others have suggested that air conditioning lowers our tolerance for heat, making us less capable of enduring heat waves. I know that virtually every older adult, black and white, with whom I grew up firmly believed that. (The last is a questionable belief if one checks the record to find the incredible number of persons who have died from heat waves in pre-air conditioned days when, supposedly, people would have been more “heat resistant,” as it were. Moreover, many without air conditioning today are still dying from the ever-more-savage heat waves that we are increasingly subject to: 35,000 Europeans died in 2003, during a month-long heat wave with which they seemed ill-prepared to cope. The Europeans may wish to sneer at the American love of air conditioning but I will bet that a good many of those 35,000 dead wished they had had it.) It was also commonly believed (and still may be) that air conditioning gave people colds. Whatever the case, there is no question that it has been a boon for people suffering from allergies and asthma, as it permits them to stay in a building without opening the windows to outside, untreated, pollen- and mold-filled air.

Finally, there are the social changes that air conditioning have wrought. The children in un-air conditioned neighborhoods (I know this well as I grew up in such an area) spent little time at home during the summer. Their homes were so hot (mothers still used the stove for meals even in the summer back during my childhood) that everyone went outside to play, organizing their own games. Few even thought of watching television, which is why the networks ran reruns all summer. It was hot outside, to be sure, but it was also highly social because everyone, all the neighbors, were outdoors, adults sitting in lawn chairs, fanning themselves, eating ice cream, gossiping, talking about the latest news stories, while the children threw a baseball, or played hopscotch or cards or checkers or Simon Says or Giant Step or listen to the radio, singing along to popular songs, or sometimes just sat around singing camp songs like “Green Grow the Rushes” or “Old Hogan’s Goat” or “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.” My mother would tell me stories on summer nights about how, during her childhood, people even slept outside during the summer. No one was in the house playing video games, snacking all the time (the heat made everyone eat less in an un-air conditioned world; air conditioning has almost certainly changed people’s diet during the summer), cocooned, isolated from one’s neighbors, as so many children are today because of air conditioning. Losing the old sense of the urban neighborhood, of urban community, during the summer has been an incalculable loss indeed.

Basile, using such diverse sources as newspapers and popular magazines as well refrigeration publications, science and architectural journals, tells a lively and endlessly informative tale about how air conditioning happened scientifically and what it has done for and to us. Despite being a title from an academic press, the book is highly accessible to the general reader. I highly recommend it.