The Elected King of Black America or the Black King of Progressivism

A new book tells the story of Jesse Jackson’s 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns.

By Gerald Early

January 4, 2026

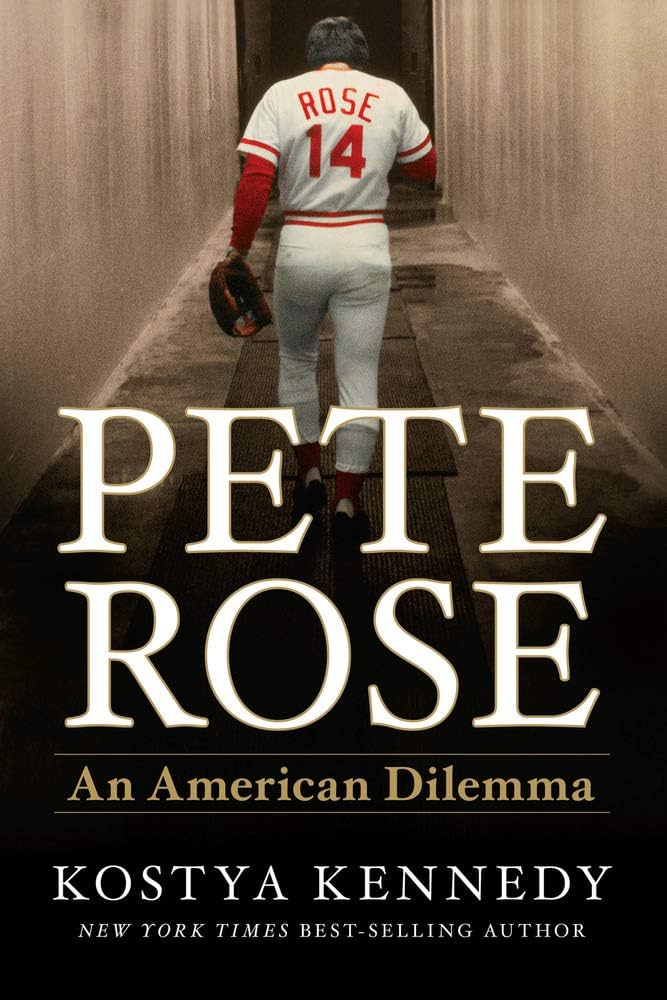

A Dream Deferred: Jesse Jackson and the Fight for Black Political Power

1. Walking through the doors of power

CNN news anchor and journalist Abby Phillip writes in A Dream Deferred: Jesse Jackson and the fight for Black Political Power about Jackson’s “blowing away”—his campaign manager’s assessment—Wall Street barons in an important meeting during his second Democratic Party presidential nomination run in 1988: “Years of tangling with wealthy business executives had given Jackson the ability to easily spin a narrative of economic justice in those very rooms. He was also aided by sheer audacity, by the belief that no room in the world was off-limits to him. And there was good reason to believe it. Jackson had come from a poor, segregated southern town, and through chance and hard work, he had spent nearly all his adult life as a public figure, becoming one of the most well-known Black men in the world.” (202)

Jackson, a charismatic combination of overweening ego, relentless energy and ambition, passionate leftist beliefs, and the certainty that his Christian God believed in his uniqueness as a leader as much as Jackson himself did and thus guaranteed him a special fate, always saw himself as the replacement of Martin Luther King Jr. He had, in the 1960s, become one of King’s top lieutenants while still a college student, electrifying and irritating, by turns. He was at the Lorraine Motel when King was assassinated in 1968. He smeared King’s blood on his shirt and gave interviews about cradling the civil rights hero’s head as he died, which was not true, but it sounded good, as if he were the anointed apostle, the son who was, in so many words, told by the father, “upon this rock I build my movement.” Coretta Scott King and the King children, according to Andrew Young, “never embraced Jesse,” probably because of this. (50-51) Jackson was never bashful about self-promotion and, like his contemporary, Muhammad Ali, he never met a reporter for whom he did not have a quote, a quip, a racial polemic, or a Black paean, as the occasion demanded. And it was in Chicago, not the South, where King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference had placed Jackson, where the young, dynamic preacher was to make his mark with People United to Save Humanity (PUSH). It is curious that while Jackson ran for president twice, he never ran for mayor of Chicago, although he threatened to on a few occasions. He never sought a state-wide office in Illinois. Perhaps they did not match the size of his ambition, or perhaps if he had done so, he would have been stigmatized as a “local” politician. Perhaps he feared losing, which would have made it impossible for him to run for the presidency.

He learned to talk to the captains of industry in the late 1960s and early 1970s when he threatened their businesses with boycotts if they did not increase their Black hiring, not just low-level clerks but also in upper management positions and in the boardroom. This was how Affirmative Action worked, as it was becoming public policy after the death of King, transactional politics, the best kind, as it did not depend on appealing to your adversary’s better nature. It was an offshoot of the 1930s local Black activism where protestors picketed businesses holding signs that read, “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work.” Pressure politics of the sort that union leader A. Phillip Randolph believed in. He said it was the only kind of politics that politicians understood and responded to.

Jackson, a charismatic combination of overweening ego, relentless energy and ambition, passionate leftist beliefs, and the certainty that his Christian God believed in his uniqueness as a leader as much as Jackson himself did and thus guaranteed him a special fate, always saw himself as the replacement of Martin Luther King Jr.

But it was this very thing that set the teeth of Black conservatives like economist Thomas Sowell on edge: how the activism tainted the result. No Black person with a job that was not “traditionally Black” (like being a janitor), no Black person who was able to obtain a white-collar job, could claim getting hired because of her or his resume. You did not get the job because of what you had to offer as an individual but because of your race and the heroic activists who pressured the White folks to hire you. They were the ones who made the White folks “appreciate” your qualifications. Black conservatives hate that kind of racial collectivism, what they feel is the tyrannical valorization of protest activism, and how all of this, as they saw it, intensified the stigma of being Black. But that is another story.

Jackson was as willing as anyone to take credit for the creation of the Black middle-class of the affirmative action era. (The origin of the modern Black middle-class is much in dispute among different ideological factions of Black folk.) He was not wrong in making his claim, but the creation came, such as it did, and such as all policy actions do, at a cost. But his activism in this way taught him he could walk through any door and talk to any person about anything. In his heyday, Blacks admired him for this. He was the ultimate race bargainer, as Shelby Steele remarked. He was what Booker T. Washington, the first race bargainer back at the turn of the twentieth century, the lone Black man who could walk through at least some front doors of Whites at the time, including the White House, wished he could have been. But Black people could hardly vote in 1900, so Washington had to supplicate, not demand. Black people could vote in ever-increasing numbers in the age of Jackson, and this made a crucial difference. Jackson represented a bloc, not a powerless, disparaged, oppressed people who had been awarded by Whites the short end of the social Darwinist stick. Nonetheless, Washington was the prototype for someone like Jackson: The guy White people wanted to deal with about race matters because he represented Black people. No other Black person, during Jackson’s salad days, could really assert that he did not represent them.

2. How voting rights divided the Black elite

Jackson arose during the age when Black people became a fully realized voting constituency. Before the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, it could be said that Blacks were a regional voting faction, their political power largely confined to the urban north and west, with highly restricted, limited voting (or none at all) in the South, where most Blacks in 1970 still lived, even after the Great Migration. (Indeed, since the 1970s there has been a trend of Blacks moving back to the South.) Surely, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act have played a role in this rise among Blacks in the legitimation that voting confers in the creation of a Black leadership class that could more effectively get spoils at the table of power. It was national news when Richard Hatcher was elected the mayor of Gary, Indiana, Carl Stokes the mayor of Cleveland, and Kenneth Gibson the mayor of Newark from 1967 to 1970. It was the dawning of the age of the big city Black mayor, with more to follow. By 1980, there would be Black mayors in Atlanta, Detroit, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, and Chicago. By now, nearly every major American city has elected a Black mayor at least once, including Philadelphia, Baltimore, St. Louis, New York, Dallas, Houston, and San Francisco.

By the time Jackson decided to run for the presidency in 1983, there was, as political scientist Adolph Reed described in The Jesse Jackson Phenomenon (1986, Yale University Press), a divide between the old guard civil rights activists, what Reed calls the protest elite whose activism made inroads against segregation and institutional racism, and the political elite of elected Black politicians with an actual quantifiable constituency and standing within a major political party. He basically sees Jackson’s presidential runs as, in part, a crisis in the Black leadership class. Who were the true gatekeepers of Black interests? Who really represented Black people? Who was in charge of, as what was called at the time, the Black Agenda? If Black people were going to run someone for the presidency in the 1970s or the 1980s, why not an experienced, elected politician, such as Shirley Chisholm, rather than a civil rights leader who headed an activist group? In some respects, Jackson’s two runs for the presidential nomination in the 1980s may have been his attempt to bridge the divide between protest elite and the political elite by actually going out and winning votes himself, electing himself, if not the president of the United States, the president of Black America. What Black politician could claim to have garnered as much support as he did in his presidential runs? What Black politician spoke to as many people, or showed as much stamina in withstanding the rigors of campaigning for the presidency? What Black politician was able to raise as much money? What Black politician had as much White Progressive support as Jackson? But as Reed points out, Jackson’s appeal for votes was based on how, as a Black political leader, he transcended “the realm of palpable constituencies of discrete individuals.” (The Jesse Jackson Phenomenon, 29) He deserved support because he was more than a mere politician.

Reed was skeptical of Jackson’s claim of having expanded the Black electorate with his runs. The evidence Reed provides is certainly inconclusive (Reed admits this), but dampens some of Jackson’s claims, particularly about how much he expanded the Black electorate in the South. Indeed, Reed takes issue with the idea of the Black South, at that time, being “a politically underdeveloped territory” that needed awakening and development by the intervention of some singular Black political figure. In 1983, the majority of Black elected officials (61 percent) were in the South, not the North. (The Jesse Jackson Phenomenon, 28) Jackson may not have created the tide of Black electoral engagement of the 1980s—opposition to Reagan’s presidency was a big motivator—as much as ridden the wave of it by being a focal point expressing Black discontent.

As Adolph Reed points out, Jackson’s appeal for votes was based on how, as a Black political leader, he transcended “the realm of palpable constituencies of discrete individuals.” He deserved support because he was more than a mere politician.

On the other hand, Jackson clearly did not diminish Black electoral participation, and he did excite many Blacks with his candidacy. As an anecdotal aside: I attended the Missouri caucuses in 1984 to support Jackson. (Missouri was still a caucus state at the time.) Veteran party workers said that they had never seen so many Black people show at the caucuses before. I was in a school room mostly of Blacks who had come out for Jackson. It was an astounding experience. The Black people there seemed so intensely motivated, so enlivened by a candidacy that stood little chance of winning. The process was time-consuming, far more so than voting in a primary. I spent more than two hours at the caucus supporting Jackson delegates, trying to become a delegate myself, although I lacked the party connections and the activist creds to have even a remote chance of the latter. Black people were willing to spend the whole night there to get Jackson his share of delegates. That was a show of commitment for his candidacy. I would not have been there had Jackson not been running. I mention as well Black political scientist and then-WashU colleague Lucius Barker, who wrote a book about the Jackson campaign called Our Time Has Come: A Delegate’s Diary of Jesse Jackson’s 1984 Presidential Campaign (1988, University of Illinois Press). I doubt he would have served as a delegate or written this book for any other Democratic candidate. These examples are admittedly small but telling. Jackson’s presidential gambits were heady times.

What annoyed the political elite about Jackson was that, as he had never held an elected office, he was not truly accountable in the way a politician normally is. He could be criticized for being a neophyte, but not for being a failure or incompetent. In effect, Jackson did not need to show results, only persistence. He ran on his charisma, his sincerity (he spoke truly and from the heart, and he was a preacher), and on his authenticity. This last being most important, for he claimed that he had always put himself on the line for Black interests, that he never abandoned or betrayed Black people, that he was unabashedly Black in White centers of power. For what he wanted, sincerity, authenticity, and charisma were enough, and more than what many of his White opponents had. He won 12 percent of the delegates in 1984 (466) and nearly 30 percent in 1988 (1,219), finishing second to nominee Michael Dukakis. Shirley Chisholm, in her 1972 Democratic presidential run, garnered 152 delegates in a campaign that was sandbagged by her inability to bring together the two factions that claimed to support her, liberal and leftist Blacks and White feminists, but bitterly disliked each other, and by a press and a party that did not take her seriously. Jackson did better than any Black person in history had ever come close to doing. He had enough leverage to even get some modest rule changes and, of course, to have each nominee ask him what he wanted to gain his support.

3. How Jackson reinvented progressivism

It could be said that Blacks made a claim for leadership of the left wing of the Democratic Party after Jackson’s 1984 presidential run. This is one of Phillip’s main contentions in her book: “‘Progressive’ was just beginning to be used to describe a movement within the Democratic Party of which Jackson believed he was the standard-bearer.’” (176) This statement is true as far as it goes but the progressive movement, in its modern sense, in connection with the Democratic Party, goes back to Henry Wallace and his quixotic 1948 presidential run.

In many ways, Phillip’s book, which overall is a fine, solidly written biographical and political study of Jesse Jackson and the rise of Black presidential aspirations in the American two-party system, would have benefitted from looking back, if only for a page or so, at Wallace’s campaign, his stature among the Democratic left, his failure, and how Jackson’s efforts differed from Wallace’s. How did Jackson succeed where Wallace failed? The biggest difference, of course, is that after failing to get the nomination, Jackson did not decide to run as a third-party candidate as Wallace did. He did not run as a Progressive Party candidate, nor as the standard bearer of a Black political party, something that many Black people wanted back in the early 1970s, a kind of fever dream of Black political independence.

What annoyed the political elite about Jackson was that, as he had never held an elected office, he was not truly accountable in the way a politician normally is. He could be criticized for being a neophyte, but not for being a failure or incompetent. In effect, Jackson did not need to show results, only persistence.

Jackson did not decide to join a Progressive Party but rather to make the Democratic Party more progressive by attracting more people to it who would be sympathetic to progressive ideas, which has happened during his lifetime. In this way, staying loyal to the Democrats, as Chisholm did as well, made it possible for Black politicians to build on each other’s efforts. Jackson built on Chisholm’s (being a man, a preacher, and a civil rights leader made him a more attractive candidate than Chisholm) and Obama built on Jackson’s (being an elected politician, more disciplined, less tied to Black American protest history, and therefore less of a protest emblem but rather a transcendent agent of change and redefinition, made him a more attractive candidate). In this way, the Democratic Party, whether it wanted to or not, established a tradition, a practice of Blacks running for the presidency and espousing some formulation of progressive ideas. It became a way for Black politics to mature.

While Wallace did not succeed despite having been White, Secretary of Agriculture under FDR and Secretary of Commerce under Harry Truman, an overall powerful presence within the Democratic Party, and the heir apparent as the leader of the New Deal after the death of Roosevelt, he did establish progressivism in the Democratic Party as an unabashed supporter of the welfare state and the New Deal. He ran because he thought that after the death of Roosevelt and with the rise of Truman, the Democratic Party was turning its back on the New Deal and the liberalism that made it a force in twentieth-century American politics. Wallace also represented a populism that looked to include everyone from family farmers to urban unemployed. Jackson remade the New Deal as the Rainbow Coalition (before Rainbow became a symbol for the LGBTQ movement), but it was essentially the same idea as the late-nineteenth-century Fusion Party. In the twentieth century, since the Depression and the rise of Henry Wallace as the savior of the American farmer, this liberal/left vision has always been, in some way, a reinvention of the Popular Front, precisely what Martin Luther King, Jr. was trying to do in the 1960s from the outside, and what Jackson, as King’s heir, felt compelled to do within mainstream liberal party politics. It should be noted how much space Phillip affords in A Dream Deferred to describe Jackson’s efforts to attract White farmers, particularly in 1988, and how he felt that to be a cornerstone of his Rainbow Coalition.

A Dream Deferred is a thoughtful book, especially for those who lived through and remember Jackson’s presidential runs: it is honest (Phillip gives us Jackson warts and all, the maddening egotism and opportunism, the rumors of infidelity), informed, highly readable, even exciting at times as she recounts the thrills of the campaigns, and well-researched (she did many interviews including some with Jackson). She explains the problems Jackson encountered with Jewish support (but not how President Carter’s firing of Andrew Young as United Nations Ambassador for secretly meeting with the Palestine Liberation Organization in 1979 presaged this); his outreach to the Arab community (facilitated by his connection with the Nation of Islam); his not-always beneficial relationship with Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan, who seemed to use Jackson’s candidacy as a platform for himself; his disorganization; the risks he ran running for the presidency (many death threats); his foreign policy triumphs in getting Syria to release a captured American pilot Robert Goodman (with considerable help from Farrakhan quoting the Koran in Arabic to Syrian leaders) and Fidel Castro to release forty-eight American and Cuban prisoners. Phillip notes as well: “When Mondale ultimately chose Geraldine Ferraro as his running mate, Jackson correctly took credit for forcing the issue onto the agenda.” (172) If only she had included Wallace, she could have made even stronger her claim that post-World War II progressivism in the Democratic Party, rooted in Depression-era leftism, was invented by Wallace, and was reinvented and became dominant in the longer run by the presidential campaigns of Jesse Jackson.