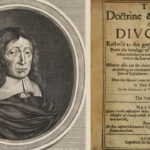

John Milton Argues for Divorce

In the most elevated terms, Milton urges an understanding of marriage altogether spiritual and intellectual, a union nearly without bodies, for in the divorce tracts he repeatedly figures marriage as the joining of rational souls, as the mind’s solace and satisfaction, its source of “comfort and peace,” an apt and cheerful conversation that hedges a man against the solitary life.