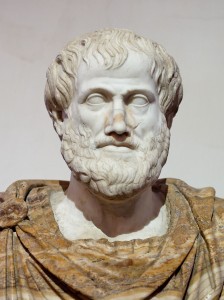

Aristotle: The master of those who know

As a general rule, people want to know the truth. “All men by nature desire to know,” Aristotle begins in his Metaphysics, “an example of this is the delight we take in our senses.”

When we understand the truth about how something works, we gain the option to control it, the prerogative to change it if necessary. New frontiers of ability and experience are opened to us. When we understood how to make fire, we accessed a new world of food preparation and enjoyment. When we understood how to make electricity, we access a new world of convenience and safety. When we understand how to build a machine, we unlock the ability to accomplish tasks that would otherwise take months, years, or be completely otherwise impossible. Knowledge and understanding, in this sense, are the source of all human power and endeavor.

But when we do not understand, we are powerless and helpless. When we do not know, we are vulnerable. Even worse, we sometimes think we know, and we are wrong. This is a particularly dangerous situation, much worse than not knowing at all, because we then stop looking for the truths, for evidence, and for knowledge. This is a lamentable state, and it is our primary problem to learn and understand how to discern truth from fiction or fairytale.

Centuries of effort have taught us how to learn and know truth. It has taught us to perform tests, to devise experiments, and to analyze the results. It has taught us to try to remove any personal bias, to listen to the verdict of nature whatever it may be, and to accept the results as truth. Most importantly, we have learned that we must be willing to abandon old ideas in the light of new evidences. This is the only way we humans have ever found to reliably learn truth.

It is therefore surprising when we, knowing how to obtain truth, attempt to explain mysterious or unclear events as miracles and the supernatural. This theme is continually repeated over generations. We seem almost desperate to believe in UFOs, alien abductions, unproven medical treatments, ghosts, bigfoot, monsters in Loch Ness, chupacabras … all seem to reflect an inexplicable yearning to believe in the mystical and supernatural. According to a 2011 poll, over 81 percent of Americans believe in angels, without anyone every having seen evidence of one!

I’m reminded of the crop circle scandal years ago. In 1991, Doug Bower and Dave Chorley began making crop circles as a prank, and people immediately decided it was alien communication. (Physics World, August 2011, “Coming soon to a field near you,” by Richard Taylor.) For years they continued their pranks, making more and more elaborate designs, until one day they confessed their joke. Instead of a giving itself a well-deserved self-deprecating punch in the metaphorical arm, the general public reaction was instead quite fascinating. Many people refused to believed them. Even after repeated demonstrations showing how they did it, many people would not be convinced. (Carl Sagan, The Demon Haunted World, 1995). The desire to believe in the mystical and supernatural, over the obvious and banal, seems almost overpowering.

We all inherit a set of biases and beliefs during our childhoods from a variety of sources. It is not that we are wrong to believe things we are told and about which we initially have no or little evidence. After all, if we demand Cartesian doubt to rule our lives, we would find it difficult to function at all. Our fault comes when/if we cease to question our ideas and beliefs, cease to seek evidence for our ideas, and hold any of them above questioning and changing. It is when we “know” the answer, and it is the wrong answer, and we refuse to understand and change our answer if necessary. We must always be striving to test out our ideas, to verify their veracity, and discard or change those ideas found wanting. To this extent, we are all experimentalists and empiricists. If we have been told that a certain chant will bring rain to the skies, or the favor of the gods, it is no fault to hope or believe it is true. But with that hope or belief, we have the moral obligation to devise series of tests to determine if that is true or a fiction. The problem lies not in believing or wanting something to be true. The moral fault lies only in failing to seek impartial evidence for our beliefs, and in failing to amend our beliefs based on our interpretation of the physical evidence.

Some suggest that there is no danger in believing in the Loch Ness Monster, or in aliens making crop circles. Unfortunately, believing in things that are not true is inherently dangerous. If we insist that hurricanes are an act of God, as my insurance company believes, and if that settles the issue for us with no further discussion, then we miss out on the knowledge of meteorology and climatology that can lead to storm predictions, warnings, and the preservation of life. If we allow ourselves to believe in ghosts, monsters, and demons, then life-ending witch trials and Inquisitions are certain to follow.

As a more and more enlightened society that has found the intrinsic value of science permeating every facet of our lives, let’s learn patience in the face of mystery and “miracle,” and give the scientist within us all a chance to logically evaluate and understand. Let’s repress the dangerous desire within us to claim something is outside natural laws until we have met the Sagan criteria for amazing claims: “Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.” THAT world will be a smarter, safer place for all of us.