Some places record the rise and fall of a significant building, or evoke historical events that took place there. Others, like the site where the notorious St. Louis public housing complex known as Pruitt-Igoe once stood, serve less as memorials than material imprints of loss and unresolved histories. This past November, bulldozers destroyed the tranquil urban forest that blanketed what remained of the larger Pruitt-Igoe footprint, at once exposing, and adding a new layer of erasure, to this record.

In its apparently dormant state, the forested site [photograph at top] may not have meant much to former residents or scholars who have been most concerned with its history; certainly, it had far-less semiotic charge than the images of the ill-fated high-rise towers, and for many, had fallen into quiet oblivion. But it had a certain evocative power. Nestled beneath the cottonwoods and honeysuckle vines, one could find piles of rubble from other development projects the city had hauled to the site, and a few fragments of the housing complex itself, including an old playground lamppost and a (still-operational) Ameren electrical substation. Over the decades, many dutiful pilgrims—architecture students, journalists, urban bloggers—visited the site in search of such remains, often taking photographs or producing videos of what they found.

Benign as the otherwise-undisturbed site seemed, Pruitt-Igoe was the target of dozens of abortive rectification schemes by city officials and local aldermen over the decades. Its long-awaited clearance must be understood not only as a gesture of political support for redevelopment but also as an act of aggression—one that mirrors a longer history of discursive and economic abuse of the north side, where neighborhoods continue to shrink away under the effects of neglect and disinvestment, as well as brick thieves. Indeed, the wide-scale NorthSide Regeneration redevelopment project headed by Paul J. McKee, Jr., who purchased the Pruitt-Igoe property from the city in 2016, and is now building an independent hospital there, is premised on such abuse. Northside Regeneration’s medical center project has benefitted from the emptying out of these neighborhoods, and in turn re-capitulated the logics of ‘slum clearance’ of preceding generations. Now that the City of St. Louis under Mayor Lyda Krewson has served Northside Regeneration with a notice of default on its public redevelopment agreement, the project may soon lose its sanction from City Hall. Yet the company owns hundreds of acres including Pruitt-Igoe, and that will not change unless McKee decides to sell.

Pruitt-Igoe’s long-awaited clearance must be understood not only as a gesture of political support for redevelopment but also as an act of aggression—one that mirrors a longer history of discursive and economic abuse of the north side, where neighborhoods continue to shrink away under the effects of neglect and disinvestment, as well as brick thieves.

And as growing swaths of St. Louis city’s midsection have been erased, it has become easier and easier, apparently, to “resolve” such unruly sites—to quiet their restive histories, and rework their public image to serve the interests of urban elites. McKee understands this very well, and has spent years on advancing a public narrative promoting rectification of the near north side. So have public officials. As a form of social and political injustice, the dismantling of the Pruitt-Igoe forest, in fact, pales in comparison to what has transpired across Cass Avenue, where the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) now is building a 122-acre high-security facility. The project proceeded despite loud opposition from local residents, who noted that it represents the gutting of yet another African-American neighborhood through the (wholly legal) tactics of slandering representation and eminent domain.[1]

Several generations of St. Louis politicians and boosters have anticipated this moment. In July 2014, when St. Louisans learned that the “site of the old … housing complex near Cass and Jefferson avenues” in North St. Louis was one of six locations being considered by the agency for their new campus, their discourse was jubilant. [2] McKee had pitched the site to the NGA in response to a request for proposals, but politicians were quick to claim credit. In the months that followed, the Post-Dispatch and others reported that the “Pruitt-Igoe site” that the city offered to the NGA—including hundreds of acres to the north and east already owned by McKee—was finally going to be rehabilitated. The NGA eventually excised the Pruitt-Igoe portion, which the agency claimed was too small, but the putative NGA site continued to be shorthanded by the media as “Pruitt-Igoe.” Even when, in April 2016, the agency officially announced that the redrawn North St. Louis tract had been chosen, at least one media outlet was still referring to the location of the $1.75 billion project as the “site of Pruitt-Igoe.” [3]

The terrain vague of the site is a testament to distance—the passage of time since the last tower fell in 1976, certainly, an event remote enough that younger residents of nearby neighborhoods grow up not knowing anything about the site, but also the dispersal from the center of the city, which has led many to view everything east of Grand Avenue as “downtown.” But the compulsion to rectify Pruitt-Igoe has a much longer history—one rooted in the “slum conditions” many public housing policies sought to correct. The site has lingered in the popular imagination for decades, and remains a haunting specter not just of urban decline, but of failed planning and social policies. In recent years, colloquial references to the site have constituted a shorthand for several of these ideas; even those who do not know the details of the complex’s dark history and cannot find the site on a map seem to “remember” Pruitt-Igoe as a site of shame.

Some of these negative associations have come to light in the context of the NGA proposal. Early supporters—state and local officials, city boosters, even some residents—characterized the plan to locate the spy agency at the site not simply as economic stimulus but poetic justice—an opportunity to right old policy wrongs, or heal often-concealed civic trauma. Jeff Rainford, Mayor Slay’s chief-of-staff, contended in 2014 that “it would be very elegant and very just if this generation of the federal government undid the injustice created many decades ago.” [4] Others have instinctively reached for the same logic of rectification, seeing redevelopment of Pruitt-Igoe and environs as the antidote to bad planning and economic decline across the city. [5]

… as growing swaths of St. Louis city’s midsection have been erased, it has become easier and easier, apparently, to “resolve” such unruly sites—to quiet their restive histories, and rework their public image to serve the interests of urban elites.

That the subject of such rectification work is not simply “failed” federal policy or embarrassing and outmoded urban planning of the sort Pruitt-Igoe is so strongly associated with, but harmful characterizations of the homes of poor and black Americans, did not seem to occur to these officials. The NGA project cannot by itself reverse this decline, or make up for longer histories of erasure, yet supporters of the project have assiduously argued that the repurposing of the site—and the 3,200 jobs that it would allow the city to retain—represents a catalyst of growth in the most depressed part of the city. [6] And that same hope could easily be transferred to the St. Louis Place neighborhood that sat at the heart of the NGA footprint. The ensuing campaign of public images justifying the project (with its newly redrawn boundaries) was not dissimilar to the one for Pruitt-Igoe one year earlier.

Given the ongoing political and material impacts—and the real human toll—of this public discourse, its history merits further consideration. Much of the public discourse about Pruitt-Igoe has turned on visual representations of the site. Early media accounts of the NGA project, for example, relied heavily upon satellite photographs (some of them digitally enhanced with street grids and other features) to evoke a sense of possibility for the 122 acres the city had promised. These photos often depicted Pruitt-Igoe as a dark green polygon surrounded by the lighter green of grassy areas and gray pockets [Figure 2], a dark welt on the city’s midsection that, in the context of urban renewal discussions, was read as a district suffering from uneven development (or what in previous decades would have been called “blight”). [7] Likewise, Google Earth photos showed the “Pruitt-Igoe site” as a virtual dead zone between Jefferson and Cass Avenues that could easily be reclaimed for another purpose.

Figure 2: A recent aerial view of the Pruitt-Igoe forest.

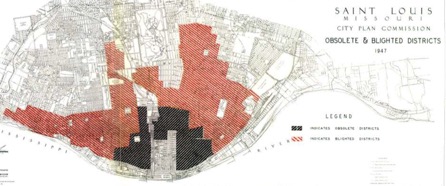

In their fixation with the evidence of density and integrity of space—and with vacancy—these images all showed “Pruitt-Igoe” as plot of land in a state of either incipient development or decay, depending on one’s point of view. In that respect, they echoed older schematics of the urban landscape such as the 1947 City Plan Commission’s “Obsolete & Blighted Districts” map [Figure 3], which authorized wide-scale land clearance following the passage of the 1949 United States Housing Act. Both the more-recent aerial photos and these historical maps serve to visually rationalize the city, and to dominate the public imagination. One diagram that combined elements of both, and was frequently reproduced in early press accounts of the NGA project, showed the six proposed locations as squares on an graphical map of the region, and made “the former Pruitt-Igoe complex” the part that stands for the whole—a powerful synecdoche for the larger tract of “undeveloped” land in need of rectification.

Despite such visually reassuring images, Pruitt-Igoe remains fundamentally ‘unresolved’ in the public imagination. Like many cultural sites associated with tragedy or dark histories, it has long been suspended in a state of material-symbolic indeterminacy, apparently resistant to planning and preservation schemes. [8] There are economic and political factors that help to explain these patterns over the years, but we should not discount the power of collective ambivalence—in this case, a simultaneous desire and inability to forget a site that embodies both the city’s hopes for a better future and its traumatic pasts. Older representations of the site, and the housing complex itself, have had an unusually long half-life in the public imagination. Popular and scholarly authors have volleyed dark public images of decline and demolition, while thousands of archival photographs of family life at the housing complex rarely have been consulted, let alone utilized in newspaper articles or academic journals. Perhaps no other American architectural symbol has been so widely and ignorantly deployed.

FIG 3: Map showing “Obsolete & Blighted Districts,” Saint Louis, Missouri City Plan Commission (1947).

Arguably, the most famous representation of Pruitt-Igoe—the image many call to mind when its name comes up—is the iconic photograph showing the implosion of one section of housing development that took place in April 1972 [Figure 4]. Taken by Post-Dispatch photographer Michael J. Baldridge, the image shows the building in a state of partial collapse, shrouded by a cloud of debris, with the city’s well-known Gateway Arch at far left. It documents a strategic ‘thinning-out’ of complex, which was both under-occupied and rapidly deteriorating due to neglect. But like video footage of the demolition that was aired nationwide on network news programs, the photo evokes, not strategic site management or rehabilitation, but violent deletion. Baldridge captured a moment of literal and figurative catastrophe for the city, producing an astonishing image that might, in both its intensity and its aesthetics, be imaginatively compared to photos of Mount Saint Helens’ eruption or the collapsing Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. Like these images, it has a mesmerizing quality, even a sublimity, although to appreciate such a quality, (as some who gathered to watch the implosion seem to have done), we must distance ourselves from the physical violence and moral implications of the act of demolition. We must view the loss of Pruitt-Igoe as a necessary, self-inflicted wound—a way to purge the city of a site that had come to embody humiliation, and to symbolize “all that is wrong with urban renewal.” [9]

Figure 4: Michael J. Baldridge’s iconic photograph of Pruitt-Igoe’s 1972 demolition. (Copyright: Polaris Images)

Undoubtedly, the photo’s growing iconicity turned on its spectacular quality, which would come, with time, to be linked imaginatively with the slow-detonating catastrophe inside the towers. As conditions worsened after the demolition, and violence escalated to a point of public crisis, the pathologizing narratives about Pruitt-Igoe solidified further, and the demolition photo became a token of retroactive confirmation bias. In coming decades, Baldridge’s image—and all that it represented—would come to emblematize the Pruitt-Igoe debacle as a whole, and serve as a warning to architects, planners, and policy-makers about the catastrophic effects of such a large-scale “planning failure.” [10] Today, the demolition photo signifies humiliation and erasure, and most who use it likely have no idea that it was generated when the city was trying to save Pruitt-Igoe, not destroy it. Perhaps for this reason, it is this photo, more than any other visual representation of Pruitt-Igoe that has resurfaced in the context of the NGA and Northside Regeneration plans.

Baldridge captured a moment of literal and figurative catastrophe for the city, producing an astonishing image that might, in both its intensity and its aesthetics, be imaginatively compared to photos of Mount Saint Helens’ eruption or the collapsing Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City.

The Baldridge image has an important counterpart in photographs of another demolition in a North St. Louis neighborhood just northeast of Pruitt-Igoe—that of nearby DeSoto-Carr. Such images exposed for public viewing both the derelict state of poor St. Louis neighborhoods that were being removed by the headache ball and the violative nature of such removal. One photo [Figure 5] shows a man driving a bulldozer that is pushing trash, pieces of building, and dirt through a now desolate-looking block. Across the way we can see the remainder of a two-unit row house, its other half having been shorn off. The painted interiors of the upstairs rooms are freshly exposed, and men walking on the roof seem to be preparing for the next stage of removal. In the background to the far right we can see mounds of what could be clearance rubble or material from Samuel Andrew’s WHOLESALE & RETAIL RAGS & SCRAP IRON business. Local commercial activity has evidently been disturbed by the clearance. Another photo [Figure 6] from the same period shows African-American wreckers salvaging timbers from wrecked buildings.

Figure 5: Clearance activity in the DeSoto-Carr neighborhood, 1952 (Credit: State Historical Society of Missouri)

Figure 6: Street side clearance in the DeSoto-Carr neighborhood, 1952 (State Historical Society of Missouri)

Neighborhood improvement may have been the motive behind such clearance, and indeed the taking of these photos. But the images themselves, with their street-level perspectives and attentiveness to the harsh realities of clearance, suggest the real toll of such improvement on established communities. In their humanizing representations of impoverished families, they conjure forth an even older set of images and descriptions of the “slum living” in St. Louis, as well as a national body of housing reform literature whose lineage starts with Jacob Riis’ 1890 How the Other Half Lives. Books like Riis’ volume, the Civic League of St. Louis’ 1908 Housing Conditions in St. Louis: A Report and R.R. Earle’s 1910 The Housing Problem in Chicago form a seminal core of urban photojournalism that places the human subject at the center of an engulfing architectural squalor. Such studies explicitly and implicitly argued for a causal relationship between degradation of the built environment and daily human suffering, and evoked empathy from generations of readers of a sort rarely given to Pruitt-Igoe residents.

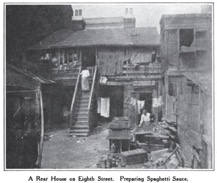

And while housing reformers’ images may have been designed to rile an insouciant public against the ravages of human poverty, the long-term impact of their work has been the ongoing encouragement of public slum clearance policies. [11] Riis pioneered the use of flash photography to heighten the contrast in each exposure, making the grime and decay of tenements seem more pronounced in black and white photography than in real life. The Civic League followed suit in the imagery of its 1908 report, utilizing photographs that were cropped or framed to omit larger context and heighten the effects of deterioration [FIGS 7-8]. Framing statements for each photo define the area boundaries, but introduce the reader to “slums” through bird’s eye views that disorient the viewer, showing panoplies of gabled and flat roofs that could be from any older district of the city, or indeed, any number of cities. [12] Subsequent images would objectify people and details even more egregiously.

Figures 7, left, and 8: From the Civil League’s Housing Conditions in St. Louis: A Report (1908)

The Civic League report presaged the later visual life of Pruitt-Igoe in its reductive depictions of the material realities of urban poverty and its ideological framing of suitable interventionary measures. This wave of reform literature included influential early characterizations of undesirable attributes of the disorderly city, its illustrations tailored to reinforce that view. Historian Gwendolyn Wright notes that this literature neglected notable features of tenement life, such as the decorative and cultural choices made by its residents, that would have suggested how upwardly-mobile ethnic groups actually improved substandard housing over time. [13] Indeed, the Civic League report’s lone representation of local ethnic customs was an image of an Italian family making spaghetti in the rear yard of their tenement [Figure 8]. The report called for the prohibition of such activity, and also any use of dwellings as workshops, home businesses or a stage for other kinds of activities that would have given residents additional economic stability. [14]

The Civic League report presaged the later visual life of Pruitt-Igoe in its reductive depictions of the material realities of urban poverty and its ideological framing of suitable interventionary measures. This wave of reform literature included influential early characterizations of undesirable attributes of the disorderly city, its illustrations tailored to reinforce that view. Historian Gwendolyn Wright notes that this literature neglected notable features of tenement life, such as the decorative and cultural choices made by its residents, that would have suggested how upwardly-mobile ethnic groups actually improved substandard housing over time. [13] Indeed, the Civic League report’s lone representation of local ethnic customs was an image of an Italian family making spaghetti in the rear yard of their tenement [Figure 8]. The report called for the prohibition of such activity, and also any use of dwellings as workshops, home businesses or a stage for other kinds of activities that would have given residents additional economic stability. [14]

DeSoto-Carr at the time of clearance in 1952 (State Historical Society of Missouri)

If north St. Louis slums in the 1908 report read as disorderly, they read as almost serene in 1950s photographs of DeSoto-Carr. Although demolition was already happening all around the poor African-American families who were dwelling in buildings that at the time had been condemned for clearance, the photos evoke the genial community-building American urbanism of Jane Jacobs and Ray Suarez. But earlier negative characterization of the neighborhood had already triggered its erasure, and the photographs suggest a degree of willed neutrality that is absent from earlier reform images and later depictions of Pruitt-Igoe. Children playing in an alley, groups of men sitting on sidewalks gossiping and families gathered on stoops and porches capture community life that embodies the traits that are so dearly desired by today’s developers, McKee among them. Indeed, such photos could be read as part of a narrative extolling the traits of community life in DeSoto-Carr.

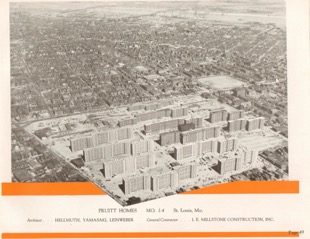

Subsequent images of Pruitt-Igoe’s construction and completion displaced these older images of urban disorder and social life in St. Louis’s doomed neighborhoods. The Stephen Gorman Bricklaying Company, masonry contractor for the project, published a portfolio in 1956 that includes several dramatic views of the site [Figure 10]. Like the Baldridge photo, the aerial images assert a sort of ownership of the eye for the viewer, who can read the housing development as a defiant mark on the landscape, an act of rectification that has little to do with the human beings who will live there.

Figure 10:Stephen Gorman Bricklaying Company pamphlet (1956)

Widely-published photographs of Pruitt-Igoe as it looked right after construction was completed [see, e.g., Figure 11] are likewise devoid of residents or material evidence of their presence, focusing strongly on the architecture. In the narrative of the site that emerged at the time, these images were understood to document a moment when modernist order annihilated the urban slum. The design of Pruitt-Igoe reflected national conventions for high-rise housing projects funded under the United States Housing Act of 1949, not local preferences (St. Louis’s city planner Harland Bartholomew in fact advocated against any high-rise public housing). It was one of the “massive projects of a unified yet distinctive appearance” that, as Wright notes, federal housing planners aggressively promoted over “small projects that blended into the surrounding neighborhoods.” [15] In fetishizing such building forms, these early images of Pruitt-Igoe asserted a sense of conquest, but also set the stage for the better-known images of deterioration that followed.

FIG 11: United States Geological Survey photograph of Pruitt-Igoe and the adjacent George L. Vaughn Homes, 1958.

Within 20 years, photographs of the Pruitt-Igoe demolition (including both the 1972 implosion and the 1976-77 wrecking-ball demolitions of the remaining thirty towers), alongside those showing neglect, filth and decay inside the towers, would together almost wholly supplant those showing a rationalizing order at the site. Press photos taken during the years leading up to the demolition depict abandoned apartments, broken windows and elevators, and graffiti-covered, trash-filled hallways, and documented the demoralizing material conditions and effects of daily violence experienced by Pruitt-Igoe residents. Many resemble war-zone journalism: doorways stand forced open, windows are broken out, and the boundaries between public and private have been violated. Such photos confirmed firsthand accounts of the living conditions—what sociologist Lee Rainwater referred to as the notorious “slum world” of Pruitt-Igoe, which, as he saw it, “condensed into one 57-acre tract all of the problems and difficulties that arise from race and poverty, and all of the impotence, indifference and hostility with which our society so far has dealt with these problems.” [16]

… the site’s long-unresolved status points to the act of deferring responsibility for those traumas, and the city’s amnesic relationship to its own histories.

In more recent years, particularly since the 2011 release of the popular documentary The Pruitt-Igoe Myth, people have come to read these scandalizing photos more sympathetically. But the images continue to reinforce the textbook narrative about the Pruitt-Igoe towers as “poorly-designed warehouses of fear … crime and despair,” and in hindsight-fashion have legitimized—indeed, given a kind of heightened pathos—to their eventual demolition. [17] The photos are often taken to represent multiple stages of an ongoing urban emergency—a housing project in incipient decline, like the DeSoto-Carr slum before its clearance, or the patchwork St. Louis Place neighborhood before it was re-ordered by the NGA. And they have come to function as a constant negative place memory that must be attended to. In his proposal to redevelop Pruitt-Igoe, Paul McKee conjured up the most disturbing aspects of the site, ranging from soil contamination to the most sordid elements of its history, as his representations have contributed powerfully to public arguments for its rectification.

Figure 12: Film still from The Pruitt-Igoe Myth (2011).

The visual history of Pruitt-Igoe thus reveals, and at times, reenacts discursive and material violence of the sort that continues to inform policy decisions in North St. Louis. In such a context, even photographs of an aging urban forest can be taken by some to document unruliness, a need for rectification. Several years ago, architect Sam Jacob summed up this legacy when walking the Pruitt-Igoe site, which he described epigrammatically as “a forest that grows out of all that socio-political debris.” [18] Such debris includes not only the detritus of “failed” development projects, and the layers of visual representation that have shaped the public imagination of the site, but also the residue of human trauma. Indeed, the site’s long-unresolved status points to the act of deferring responsibility for those traumas, and the city’s amnesic relationship to its own histories.

Figure 13: Rendering of the proposed urgent care hospital at Pruitt-Igoe (2017).

Figure 14: The clearance of the Pruitt-Igoe site today. (Credit: Michael R. Allen)

This long arc of Pruitt-Igoe’s contradictory history reaches an apparent apogee at this current moment, as the land is prepared for construction of a small for-profit hospital [FIGS 13-14] that will serve a “medical desert,” and whose closest neighbor will be a high-security NGA facility whose chief function, appropriately enough, is to generate and analyze digital satellite imagery. When St. Louis is viewed from that level, many things—people, the particularities of place, the historic memories, the evidence of past acts of aggression—seem to dissolve, or resolve, into visions of a prosperous future. But the problematic history of the Pruitt-Igoe site has not been resolved, and its deeper significance, we contend, has been only vaguely understood, submerged as it remains beneath an uncleared rubble of collective ambivalence.