In the run-up to the 2008 Presidential election, America buzzed at the possibility of electing an African American to the nation’s highest office. But for many, Barack Obama would become not only the “first black president” but the “first basketball president,” and the candidate did not shy away from the latter moniker. Playing basketball as a superstitious practice before every primary after New Hampshire (a loss he attributed to the fact that he did not play), candidate Obama gained viral web fame for shooting—and making on his first attempt—a three-pointer in front of U.S. troops in Kuwait. By the time of his inauguration, understanding Obama’s affection for basketball—as well as his playing abilities on the court—became a pressing media concern beyond the sports pages. In one especially prominent example, CNN’s John King sat down with NBA Legends Bill Russell and Earvin “Magic” Johnson, along with then-current NBA players Grant Hill, Steve Nash, and Chris Paul. Watching video of Obama on the court, King asked the players to describe Obama’s game and discern what it might tell Americans about him. “He’s smart at the game,” commented Johnson, “he’s always got his head up, looking for the open man.” Praised as unselfish and fundamentally sound, Barack Obama the basketball player would be unlike his predecessor, the panel seemed to say, the one-time baseball executive George W. Bush.

Just as “Barack O-Baller’s” proclivities offered beltway media entrée to sports, the sports media embraced their opportunity to talk politics. ESPN college basketball reporter Andy Katz has gone to the White House to get Obama’s NCAA “March Madness” picks in each year of his presidency.[1] Sports Illustrated writer Scott Price played one-on-one with candidate Obama in December 2007, losing to him twice before asserting: “I came away from the whole thing thinking he didn’t need us … He has that Kennedy cool [and] nothing I learned about him later in the campaign really surprised me.” And just before Obama’s swearing-in, in the January 19, 2009 issue of SI, senior writer Alexander Wolff penned a 4,300-word longform piece titled “The Audacity of Hoops.”[2] Citing the conflicting need for individual excellence and team cohesion as the “tension at the heart of hoops,” Wolff sanguinely postulated that “maybe, just maybe, Americans chose [Obama] as their next president because they too have come to recognize that in the end it’s not about you, it’s about the team.”

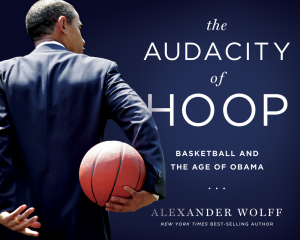

Six years later, that magazine article has become a book from Temple University Press, its title de-pluralized to The Audacity of Hoop. Wolff’s expanded text is complemented by rich visuals, mostly in the form of pictures from official White House photographer Pete Souza, along with inset features like the “Hardwood Cabinet”: a collection of mini-biographies profiling the basketball backgrounds of Obama confidants from David Axelrod and Eric Holder to Samantha Power and Susan Rice. Wolff’s tone has changed from the heady optimism of his early 2009 article, before right-wing politics had firmly coalesced around stopping Obama at any cost, to something akin to the pragmatic, slightly frustrated notes one detects in the President’s voice in the twilight of his second term. Even so, Wolff’s basic premise remains the same. As Obama’s brother-in-law, Craig Robinson—the one-time head basketball coach at Brown and Oregon State—puts it, basketball is the reason “he’s sitting where he’s sitting.” And whether the reader is convinced by this notion of Obama’s political career as causally determined by his affection for basketball, Wolff’s text cogently and poignantly demonstrates its usefulness as a defining metaphor.

Young “Barry” Obama played high school basketball, but he only made varsity as a senior, and he didn’t appreciate the limited minutes he received. Punahou High School was a powerhouse, crushing Moanalua High 60-28 in the 1979 state championship game, and Obama’s in-season petition for more playing time was rebuffed by head coach Chris McLachlin. Wolff recounts the tale, along with Obama’s later recognition of his limitations—“I wasn’t as good as I thought I was”—in service of a larger dialectical argument positioning the “first basketball president” as both principled and pragmatic: of the team, but not in thrall to it. As such, it is important for Wolff that Obama played organized ball, but also that he thrived in pick-up versions of the game, that he understood the importance of coaching and team play, but also embraced creativity and compromise. “Pickup ball,” Wolff writes, “entails collective governance and ongoing conflict resolution … positioning oneself to call next, setting up another player so the favor might be returned, soothing the temper and ego that can be as confounding in one’s own teammates as in an opponent.” It requires, in other words, “the skill set of the politician … a quorum of players who can metaphorically, as Obama did literally, carry both Indiana and Vermont.”

As Obama’s brother-in-law, Craig Robinson—the one-time head basketball coach at Brown and Oregon State—puts it, basketball is the reason “he’s sitting where he’s sitting.” And whether the reader is convinced by this notion of Obama’s political career as causally determined by his affection for basketball, Wolff’s text cogently and poignantly demonstrates its usefulness as a defining metaphor.

But beyond the campaign trails, on which Obama’s “protean … ability to change diction and cadence according to the audience he addresses” recalled his ability to easily alternate between taking the reins or deferring to teammates on the court, Wolff is left to ask: “How does a presidency use a sport to govern?” The answer, he asserts, lies in “small, symbolic gestures and larger tactical plays alike.” For the former, as Pete Souza’s photographs ably demonstrate, the president has used the basketball court on the converted South Lawn tennis facility to welcome—and occasionally play alongside—staffers, rival politicians, disabled veterans, and honored foreign dignitaries, among others. For the latter, Obama has tapped the leadership and celebrity of NBA players both to spearhead his Presidential Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition and to help convince millions of Americans to sign up for healthcare via the Affordable Care Act on its once-troubled website, HealthCare.gov. NBA stars LeBron James, Dwyane Wade, Kobe Bryant each filmed PSAs asking basketball fans to get covered. Finally, continuing a long American tradition of using sports to project soft power, the President and then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton created “Sports Envoys,” which sent American athletes and coaches overseas, and “Sports Visitors,” which welcomed foreign athletes to play games and attend clinics stateside.

Of course, Obama himself has been portrayed as foreign by political opponents who demanded to see his birth certificate and claim that he is a Muslim born in Kenya. And Obama’s connection to basketball, Wolff posits, has helped him combat such baseless claims in a way that merely denying them, or even disproving them, cannot. “The game laid out a powerful counternarrative,” portraying Obama as just “one of the guys,” hooping in the back yard. But whose back yard? If Obama was not a foreign threat, then at least he could be portrayed as a domestic one: While the mythos of basketball includes a rusty hoop tied to a barn door in whitebread Indiana, it also features such a hoop on a telephone pole on the south side of Chicago. Which is where the fact that Obama is the “first basketball president” and the “first black president” most obviously converge. Even so, although Wolff does not explicitly say so, the connections between Barack Obama, the “first basketball president,” and Barack Obama, the “first black president,” are tenuous at best.

In 2008, a John McCain attack ad attempted to leverage such associations by comparing Obama to former NBA All-Star Allen Iverson, who famously sported cornrows and a plethora of tattoos, calling both “blinged-up, [and] camera hungry.” Unfairly associating Iverson with a fear-mongering caricature of black masculinity that has been leveraged throughout American history to naturalize systemic oppression, the advertisement positions basketball as a threatening game that unites black people via stereotype as surely as the one-drop rule. But Obama’s basketball legacy, like his racial and cultural identity, is more complicated than that. As Wolff points out, “through his first two years in office Obama mentioned race and racial issues…less often than any Democratic president since the sixties.” Obama has been more outspoken on racial matters in his second term, participating in the ceremonies commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the march from Selma to Montgomery and increasing the prominence of his non-profit initiative for young minority men, the My Brother’s Keeper Alliance. Yet, as Wolff posits in quoting The Nation’s Dave Zirin, Obama “has been very measured on race…yet basketball, he’s let run.” As a matter of idiomatic expression (wherein Joe Biden is described as doing “things that don’t show up on the stat sheet”), when it comes to parenting (wherein Obama has served as a part-time coach for his daughter Sasha’s team) and his marriage (wherein the President and First Lady famously shared affections on the “Kiss Cam” at a game at Washington’s Verizon Center), for Wolff Obama’s association with basketball does not racialize him, it humanizes him. He asserts: “in a growing nonwhite and Millenial population, basketball [has] spilled beyond the bounds of race.”

In the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement and the massive protests that have taken place throughout the country in the last 18 months, the notion that Obama’s basketball jones augurs the dawn of a postracial nation rings hollow. Fortunately, Wolff’s final section, “The Game in the Age of Obama,” provides a final assessment of “the first basketball president” that is more realistic and yet still hopeful.

Left as a note of triumph, as Wolff was wont to do in 2009, such a statement would rankle. In light of the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner at the hands of police, the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, and the massive protests that have taken place throughout the country in the last 18 months, the notion that Obama’s basketball jones augurs the dawn of a postracial nation rings hollow. Fortunately, Wolff’s final section, “The Game in the Age of Obama,” provides a final assessment of “the first basketball president” that is more realistic and yet still hopeful. Examining how the NBA has changed since 2008, when Obama was elected and the NBA “was just beginning to stir from a prolonged funk,” Wolff posits that basketball not only changed Obama, but Obama changed basketball. He notes that candidate Obama was popular with both NBA management and the league’s majority African American labor force. Remarked NBA deputy-cum-commisioner Adam Silver: “The way we saw it … a vote for Obama was a vote for basketball.”

By 2014, however, when NBA stars like Derrick Rose and LeBron James wore “I Can’t Breathe” shirts during pre-game warmups in solidarity with those protesting the death of Eric Garner—a violation of both NBA uniform policy and the league’s desire that the game be a politics-free zone—Obama’s effect was less welcomed by Silver and the NBA owners. Indeed, “more and more players began to focus on the world beyond the baselines and see it in the light of politics.” The Phoenix franchise wore “Los Suns” jerseys in 2010 to protest Arizona’s retrograde anti-immigration law. James and his teammates in Miami were photographed in hoodies to protest the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012. In 2013, Jason Collins, a journeyman NBA center, became the first active male American athlete in one of the four major professional sports to openly identify as gay. The hyper-commercialized, politically neutral, globalized athlete-as-icon, manifested most famously by Michael Jordan, was no longer the aspirational model. Noted Obama of James: “LeBron is an example of a young man who has, in his own way and in a respectful way, tried to say, ‘I’m part of this society too’ and focus attention. I’d like to see more athletes do that.” After all, as Wolff remarks, “if sports came to serve as a staging ground for national conversations … it was because American society featured a vanishing number of public squares in which discussion of any kind could take place.” In a fragmented media landscape of ideological echo chambers, this is perhaps why it matters most that Obama is “the first basketball president.” The notion that sports leads politics, represented in feel-good accounts of Jackie Robinson ending racism, have long since failed to pass muster. Yet perhaps the true audacity of hoop in the age of Obama is that off-court political issues are considered by the widest swath of American publics when voiced by those on it.