The year 1968 was a time of immense change and revolution as global societies grappled with disparities in diversity promotion, identity awareness, and sovereignty declaration. Nations in the Middle East and northern Africa confronted similar dilemmas. For intellectuals and officials throughout the region, 1968 served as a period of reckoning and departure. Following Israel’s decisive victory over Egypt during the 1967 Six Days War, the bright sheen of secular Arab nationalism began to fade dull. In its place arose the pan-Islamist current of the 1970s that, in the words of Mohammed Ayoob, “became a surrogate for nationalist ideologies, seamlessly combining nationalist and religious rhetoric in a single whole.”[i] For many, this nascent political movement served to counteract the British, Dutch, French, Italian, and Russian colonial impositions of the past and shape a sovereign, post-colonial future.

In January 1968, Great Britain announced an absolute military withdrawal, scheduled for 1971, from its former colonial holdings bracketing the Indian Ocean.[ii] The declaration ensured Britain’s departure from areas “East of Suez,” especially the Persian Gulf. But what transpired in its former realms south of the Suez Canal? In particular, what spurred Islam as a governing ethos in areas long-beholden to the machinations of colonial administration? This article will compare Sudan and Yemen, two countries that exemplify the complexities of Islam as politics. While both countries witnessed British imperial rule and an enduring North-South political divide, they have experienced significantly divergent political trajectories since 1968. Following decolonization, political expressions of Islam there have evolved through the tenuous association of Muslim organizations alongside authoritarian regimes, both exhibiting convergent and conflicting ambitions within localized contexts.

Islam as politics

I want to clarify some terminology before explaining how Islam is deployed as politics in Sudan and Yemen. “Political Islam” is a phrase that refers to the fusion between Islamic piety and political utility. In many ways, Islam has always been political, with mechanisms including consultation (shura), religiously sanctioned warfare (jihad), and alms (zakat) integral to the early faith community’s stability. However, contemporary political Islam arose as an intellectual response to European colonial endeavors. Reformist thinkers like Rashid Ridda strove to purify what they saw as a corrupted and weakened Muslim community by emulating the original tenets of Islam. Hasan al Banna, an Egyptian school teacher, utilized elements of reformist thought when establishing the Muslim Brotherhood organization in 1928. The interaction between the reformist intellectual genealogy and Wahhabism–the jurisprudence of the 18th-century theologian Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab that spurred a revival project indigenous to central Arabia–inspired many politically oriented groups in the Islamic world. Political Islam is a useful shorthand, especially for this article’s title, and I use it in my writing. However, it is too broad of a descriptive category to analyze the minutiae of Islamic political actors in a thorough way. Luckily, there are more granular concepts.

While both Sudan and Yemen witnessed British imperial rule and an enduring North-South political divide, they have experienced significantly divergent political trajectories since 1968.

Analysts and scholars typically describe the fusion of political ambition and Islamic motivation with a three-part classification. Islamism is the promotion and utilization of Islamic precepts to imbue political and social institutions with an Islamic character. Islamist groups are typically pragmatic and usually, though not always, avoid armed confrontations. Graham Fuller emphasizes that Islamism is “a religious-cultural-political framework for engagement on issues that most concern politically engaged Muslims,”[iii] such as social justice and piety. The Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt is a prime example of this. Next is Salafism, or an expression of Sunni Islam that seeks to emulate the pious forbearers (al salaf) that lived during the time of the Prophet Muhammad. They frequently shun the political vigor of mainstream Islamist groups, opting instead to deploy a “quietist” approach to social change oriented with Islamic law (sharia). Finally, there is jihadism, or the merger of modern fighting tactics with classical jihad injunctions to confront a state actor in asymmetric warfare. I opt for a lowercase “j” due to armed jihad’s diverse historical application, from Sufis in 1830s Algeria, Shias in 1960s Lebanon, and Sunnis in 1990s Indonesia. Despite common mischaracterizations, jihadi groups are not “crazy” or irrational; rather, they believe that violence is the best means of casting off colonial or state oppression in the aims of a particular Islamic ideal. The fusion of the latter two categories results in a hyper militancy known as Salafi-jihadism, most aptly embodied in al Qaeda and the Islamic State (ISIS), which seeks to implement militarily a global, orthodox caliphate.

In writing on Sudan and Yemen, I opt for Islamism as my analytic and descriptive focus for two primary reasons. First, the interplay between colonial legacy, authoritarian governance, and Islamically-oriented political parties in these two countries demonstrates the syncretic forum in which Islam as politics operates. More importantly, though, I want to affirm that politically active Muslims are much more than the extremists that dominate our newsfeeds. Far too many observers lump organizations possessing drastically different strategic objectives into the nebulous basket of political Islam. A common fallacy is to conflate the nationalist struggle of Hamas with the global ambitions of ISIS, for example. My goal for this article is to elucidate the Sudanese and Yemeni Islamist movements to demonstrate their political calculus within the changing tides of colonial rule, regime amicability, and geopolitical transitions.

The rise and fall of Sudan’s Islamists

The briefly lived–1885-1899–Islamic state of Sudan’s Muhammad Ahmad al Mahdi served as an early challenge to colonial rule in favor of a pristine sharia. It also spurred British efforts to reform Islamic law to meet the aims of colonial control. This led to the formation of an English-educated class of local administrators (effendi) who functioned as conduits for projects of moral progress and material development, which the British believed essential for manufacturing a “civilized” Islam.[iv] The British hearkened to their legislative experiences in India to introduce appellate courts, incorporate interest banking, and suppress the spectacular rendition of corporal punishments (hudud) in criminal cases. Their efforts bifurcated the private and public spheres, wherein sharia maintained supremacy in ritual and personal status, while British common law heavily regulated civil society.

Britain’s efforts to bureaucratize the public realm provided the space for Sudanese Muslim intellectuals to organize. Thus, nascent branches of the Muslim Brotherhood formed a preliminary conference in 1954 that materialized into the Islamic Charter Front (ICF) by 1964. A genealogy of Sudan’s Islamist movement must begin with its primary architect–Hasan al Turabi. Educated at the Sorbonne, his role as Dean of Law at Khartoum University afforded him the opportunity to steer the movement and gain support from Sudan’s students, trade unions, and women’s groups. As Mustafa Abdelwahid proclaims, al Turabi’s schooling in Islamic tradition and European law allowed him to “sit comfortably astride modernity and tradition, pragmatism and idealism, calculation and faith.”[v] He sought to translate his aim for Islamic renewal (tajdid) into a viable political project through a partnership with a traditional governing entity.

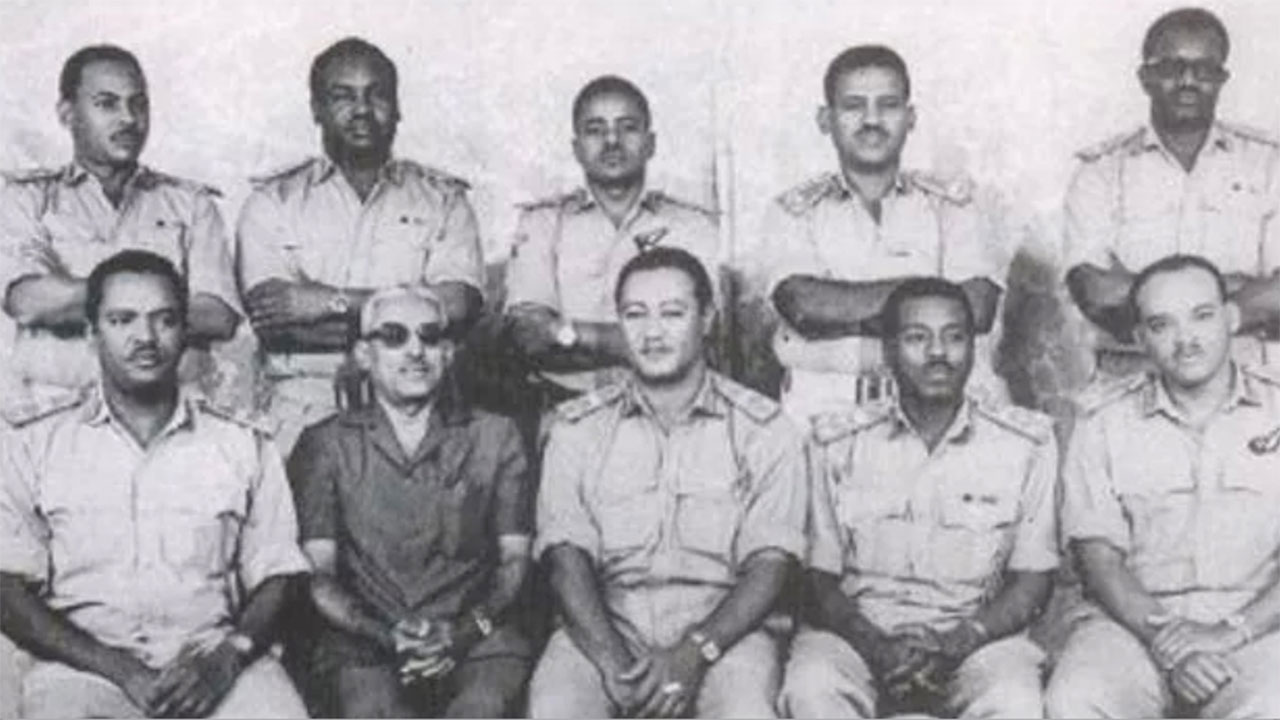

A covert meeting between General Gaafar Nimeiry and fellow officers in autumn 1968 sowed the seeds for a military-Islamist partnership that would propel the Islamist movement to governance. Following Nimeiry’s 1969 military coup, the Islamist movement served in an oppositional capacity. However, following the 1977 National Reconciliation Accord, the ICF began inserting its membership into the upper echelons of the Sudanese military and judiciary. It helped enact the September Laws of 1983, through which Nimeiry deployed hudud punishments, including amputations and lashings, to suppress political dissent. His undoing was the controversial hanging of a Muslim opposition figure named Mahmoud Mohamed Taha, an event which the ICF seized upon to depose Nimeiry in 1985. The Islamist movement was in prime position to solidify its national authority.

A covert meeting between General Gaafar Nimeiry and fellow officers in Autumn 1968 sowed the seeds for a military-Islamist partnership that would propel the Islamist movement to governance.

The movement, now under the name the National Islamic Front (NIF), aligned itself with General Omar al Bashir, who came to power in 1989. The NIF-al Bashir alliance allowed al Turabi to actualize his Islamic state vision. He applied Islamic notions such as submission to the one God (tawhid) to elevate sharia as the national legal system and to target separatists in Darfur and southern Sudan. Al Turabi’s assertion that “the protective shield of the shari‘a” promoted “a direct government of and by the people”[vi] conflicted with the reality of authoritarianism shrouded by a thin veil of Islamic religiosity. The Islamist movement, embodied in the NIF, was at the height of power from the early- to mid-nineties. Al Turabi was a well-known regional figure and even hosted the former al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden for a brief period during the decade. However, fractures in the al Bashir-NIF alliance were beginning to show.

Al Bashir, eager to entice foreign confidence and investment as oil refinement increased in the late 1990s, relegated the Islamist movement to the peripheral status it endured prior to its détente with Nimeiry. First, al Bashir renamed the NIF as the National Congress Party (NCP), scrubbing it of any Islamic connotation. Then, he expelled al Turabi from the party in 1999, ultimately imprisoning him multiple times before he died in 2016. Finally, the NCP “purged itself of major Islamist figures and [their] ideological baggage,” installing allied development and military technocrats to “establish a more politically flexible administration.”[vii] This has resulted in an ineffective Islamist opposition, spearheaded by al Turabi’s Popular Congress Party, that commands little electoral influence. Sudan’s Islamist movement miscalculated in its marriage of convenience with military regimes, especially that of al Bashir, which commanded ultimate control over the state apparatus. Try as they might, the Islamists could not beat the generals at their own bureaucratic maneuvers, and the latter solidified their rule.

Yemen’s Islamists long game

If the crown jewel of the British imperial crown was India, coaling stations such as Aden in southern Yemen served as scaffolding to hold it firmly in place. The British prized Aden’s natural deep-water port and incorporated it as a province of British India by 1839. They administered territory from the southwestern corner of Arabia to the deserts of Hadramawt in central modern-day Yemen through crafting alliances with local tribal leaders. As Charles Schmitz notes, the British gradually established princely statelets, which eased the tasks of “controlling the countryside and preventing hostile imperial powers from intervening.”[viii] The primary imperial power of concern was the Ottomans, who tenuously administered the northwestern highlands of Yemen and its Zaydi inhabitants, a branch of Shia Islam unique to Yemen. Unlike colonies in Africa, the Aden Protectorate was not an acculturation project; its purpose was supporting transportation to the British Raj. As such, the colony lacked the civic mobilization of Sunni social organizations that occurred in Sudan.

Mirroring trends throughout the Middle East, Yemen experienced 1968 as a link between years of shifting borders and evolving ideologies. In North Yemen, the secular-nationalist Yemen Arab Republic concluded a six-year-long war against the ousted Zaydi Imamate theocracy. A few months prior, in November 1967, the People’s Republic of South Yemen cast off British authority in favor of Marxism. These transitions resulted in the marginalization of political expressions of Islam, both Shia and Sunni, in favor of petro-politics driving North Yemen and the Cold War ideological battle brewing in South Yemen. A notable exception was the Islamic Front, a coalition of the Muslim Brotherhood and tribal fighters who helped the Yemen Arab Republic subdue a brief insurrection waged by the National Democratic Front in 1979. For the most part, though, Islamist networks remained connected to informal tribal patronage networks, preferring peripheral autonomy to constrictive governmental association.

Mirroring trends throughout the Middle East, Yemen experienced 1968 as a link between years of shifting borders and evolving ideologies. In North Yemen, the secular-nationalist Yemen Arab Republic concluded a six-year-long war against the ousted Zaydi Imamate theocracy. A few months prior, in November 1967, the People’s Republic of South Yemen cast off British authority in favor of Marxism.

North Yemen’s president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, cognizant of the commercial utility of South Yemen and the weakness of its fractious political landscape, merged the two Yemens into the Republic of Yemen in May 1990. According to Schmitz, Saleh sought to strengthen traditional tribal affiliations and form new Islamist political groups in the South “as a means of guaranteeing the destruction of the social base of socialism.”[ix] The Yemeni Reform Group (Islah) formed in September 1990 as big tent assemblage of mainstream Muslim Brotherhood members, conservative Salafis, and a spate of Wahhabi thinkers under the tutelage of Sheikh Abd al-Majid al-Zindani. Islah, lacking the structural rigidity of other Islamist political parties, whether the NIF in Sudan or Jordan’s Islamic Action Front,[x] has been able to deploy its cadre of government technocrats, grassroot activists, and conservative tribal elders to diversify its political engagement and serve as the conduit of mediation between Sana’a’s political core and the regional, tribal periphery. It weathered Yemen’s brief 1994 civil war and was on an upward trajectory fueled by Saudi Arabian support. However, with yet another iteration of a decisive Saleh victory, the regime viewed Islah with diminishing utility.

A sweeping electoral success for Saleh’s General People’s Congress in 1997 relegated Islah to opposition status. The party, in turn, formed a unique coalition of five disparate parties–the Joint Meeting Parties–in 2005, but it suffered from the dual strain of political irrelevancy and waning Saudi support as the latter assumed a more cautious position toward political Islam. President Saleh’s resignation following the 2011 Arab Spring, as well as the subsequent appointment of Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi to Yemen’s presidency, has proved an advantageous opportunity for Islah to regain political influence on the national stage. Many of Hadi’s cabinet members, notably Vice President and Lieutenant-general Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, are affiliated with the group. Islah promulgates its goals, covertly, through various media outlets prominent in southern Yemen, such as al Masdar Online. However, the group also remains pragmatic and, for the most part, out of the political spotlight.

Islah has weathered Yemen’s current conflict well. The “civil war”–which is in reality a regional geopolitical struggle wherein Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Iran all vie for influence–began in March 2015 as Saudi Arabia commenced an air campaign against a Zaydi Shia rebellion called the al Houthi Movement that expelled President Hadi from Sana’a in early 2015. Islah actively seeks to ameliorate Saudi and Emirati concerns over its historic links to the Muslim Brotherhood, and the three held a meeting in December 2017 to discuss avenues for enhanced cooperation. Thus, while Islah lacks official authority, this manifestation of Yemeni Islamism remains quietly on the periphery, prepared to vie for power in a post-conflict Yemen.

Revolution vs. Reform

Islamist movements must be contextualized within their respective national circumstances. The strategic calculus needed for one group would hinder another just across the Red Sea, and vice versa. We have seen in the Sudanese and Yemeni cases that political parties that utilize Islamic precepts are not merely Muslim Brotherhood franchises; indeed, both the NIF and Islah had, at best, tangential connections to the core group. I say all this to assert that Islamist movements are not monolithic. This section will focus on how the Islamist movements in Sudan and Yemen have participated in party politics.

The Sudanese Islamist movement wagered that an intimate linkage with the state represented the best means of rule. Olivier Roy identifies this strategy of power as the “revolutionary pole” through which “the Islamization of the society occurs through state power.”[xi] This top-down style has the benefit of immediate influence in educational curriculums, domestic legal edicts, and foreign policy trajectory. However, it also enmeshes a movement’s structure within the rigid bureaucracy of military regimes that are quick to reduce support to Muslim partners as political circumstances prove advantageous. Al Turabi, in a bid to become the “executive prime minister” under the nose of al Bashir, advocated for more regional autonomy in Darfur.[xii] His gamble failed, leading to his 1999 expulsion from the NIF, the gutting of the organization, and the slow death of the Islamist movement. The revolutionary, or what Jacob Olidort terms the “institutional”[xiii] association with al Bashir’s military coup government, was a fatal flaw that led to an inability to counteract regime pressure.

We have seen in the Sudanese and Yemeni cases that political parties that utilize Islamic precepts are not merely Muslim Brotherhood franchises; indeed, both the NIF and Islah had, at best, tangential connections to the core group.

The Yemeni Islamist movement lacks the organizational cohesion that characterized Sudan’s. There were projects for Islamic schooling and provision of social services, but nothing to the institutional level of Sudan’s NIF, even under the Islah party. Thus, returning to Roy, we can position Yemen’s Islamists on the “reformist pole” because their “social and political action aims primarily to re-Islamize the society from the bottom up.”[xiv] Islah seeks to imbue Yemeni life with Islamic principles and teachings. Importantly though, it has never dived headlong into this project as an official element of the state, opting instead for a mediating role that bridged President Saleh’s intricate system of patrons from Sana’a, Aden, and beyond. Even its opposition role beginning in 1997 was muted, avoiding direct confrontation with the state. Thus, Olidort’s characterization of “accommodationist” Islamist parties, or those which “engage politically relevant themes without challenging existing institutions or directly becoming involved in formal politics,”[xv] is a great description for Islah. It has lived on the margins of official state politics, allowing it to deflect Saleh’s coercion, and the power struggles of “civil war” Yemen, in ways the Sudanese Islamist movement could not against al Bashir.

The Gulf pivot

The geopolitical jostling and palace intrigue that characterize Arabian/Persian Gulf politics actively impact both Yemen and Sudan. The Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)–a cultural, military, and political cooperative between the six Arab nations that bracket the Persian Gulf–strives to curtail Iranian expansion in the broader Middle East. Saudi Arabian money and policy largely drive the GCC, and Yemen and Sudan factor heavily into their plan for regional hegemony. The Saudis have long held the strategic ambition to influence domestic policies in both countries, but their tactics have adapted to the priorities of the moment. Their original calculus for bolstering Islamic cooperatives through financial and spiritual proselytization (dawa) has transitioned to a more economic and military calculus that aims to augment their own weakness vis-à-vis Iran. The primary theater in which Saudis play out their regional struggle is in Yemen, where they call on specific Yemeni militias and Sudanese military forces to perform their bidding in a conflict that is exhausting the blood and treasure of all actors.

Practitioners of political Islam have been the biggest beneficiaries of the current conflict in Yemen. The al Houthis, the Iranian-backed revolutionary group that has controlled large swaths of northern Yemen since 2015, proudly declare as an official statement: “God is great, Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse the Jews, Victory to Islam.” Despite this staunch rhetoric, the group is more concerned with Shia sociopolitical equality than a resurgence of the historic Zaydi Imamate. In Taiz, a frontline city in Yemen’s near three-long-conflict, the Saudis support a Salafi militia called the Abu Abbas Brigade, which may have ties to al Qaeda. Then there is Islah, which bets on the continuation of President Hadi as a politically viable actor in Yemen. The Saudis, who have taken to the skies in their failing effort to bomb the al Houthi insurrection into submission, contracts its ground war out to al Bashir, who is all too willing to deploy his Sudanese forces.

Since its post-Islamism transition beginning in 1999, Sudan asserts its Sunni-Arab identity to curry alliance with and investment from Saudi Arabia. The regime fields hundreds of soldiers for the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen, with many serving in dangerous combat roles in the northwestern governorates. Sudan also joined Bahrain, Djibouti, Egypt, and the Emirates in supporting Saudi in its ongoing diplomatic rift with Qatar, which the Saudis accused of collusion with Iran. In exchange, the Saudis reward Sudan with cash payments for agricultural, irrigation, and hydroelectric projects.[xvi] Khartoum thus frames its interjection into Yemen as a liberation of Yemeni Sunnis from the Shia al Houthi rebellion. This, in turn, leads to more regional support for the regime, and importantly, the ability to deflect criticism over internal mismanagement and political quandaries. Al Bashir’s regime is now stronger than ever, and it will continue to paradoxically promote itself as Sunni Arab while simultaneously suppressing nascent Islamist groups, in a bid to retain absolute authority.

Divergent trajectories

The Islamist movements in Sudan and Yemen are prime examples of the need for analytic precision and descriptive caution. They are representative of the diversity both within and between groups that rally Islamic religiosity as a political mechanism. Sudan’s movement is on a slow and tired downward trajectory, owing to the National Islamic Front’s naïve association with the al Bashir military regime. Islah, on the other hand, is in a fairly stable, and upwardly mobile, position as it waits out the war waging in Yemen. Unlike the NIF’s Hasan al Turabi, a sort of Islamic revivalist Icarus, the broad leadership of Islah never sailed too close to the sun. They realized the danger of intimate cooperation with the state apparatus, and they are in as good a position as any strategic actor in Yemen to secure their diplomatic interests when the war inevitably concludes. I believe it is a safe evaluation to say that the Sudanese Islamist movement has failed to imbue national governance with a strong Islamic character. However, owing to tenuous political condition during Yemen’s conflict, the jury is still out. Both case studies offer important lessons for us all; namely that Islamism is diverse and that its success is directly correlated to its level of interaction with state structures.