Preface: In which we offer a personal memory

“To life, to life, l’chaim”

Most of us know Sholem Aleichem from “Fiddler on the Roof,” the iconic American musical about a Jewish dairyman and father of five daughters living in the Pale of Imperial Russia in 1905. Even if we do not know him, we do.

The musical by Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick, and Joseph Stein, was based on Sholem Aleichem’s stories about Tevye, the milkman. The original Broadway production, which opened in 1964, starring Zero Mostel was my own personal introduction to live theater and the American musical.

The theater where it played had retained much of its original, 1920s décor elegance: gilded French molding, ornate chandeliers and plush velvet seats in deep red. My mother brought a pillow for me to sit on so that I would be able to see above the person in front of me. Evidently I was still young enough to suffer the indignity, but old enough to remember. My other memories are less clear. I was enthralled just to be in the theater, frightened by the ghost scene, and reduced to tears when Hodel sang “Far from the Home I Love.”

While I remember the great Mostel, I don’t know if I saw Bea Arthur, Bette Midler or Pia Zadora as Yente or one of the daughters. Except for an odd story here or there, I did not encounter Sholem Aleichem, a major force in modern Yiddish literature, again. Not until studying modern Hebrew literature up to the Odessa period.

Chapter One, The Words of Jeremy Dauber: In which we present an overview of our author, his subject and his project

When you die, others who think they know you, will concoct things about you … Better pick up a pen and write it yourself, for you know yourself best.

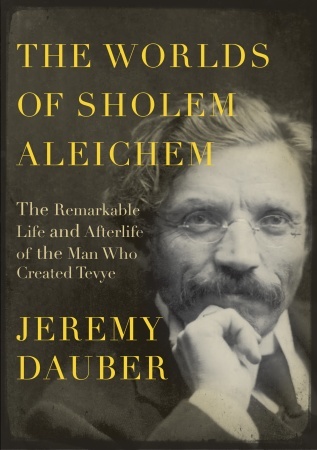

Jeremy Dauber is currently the Atran Associate Professor of Yiddish Language, Literature, and Culture in the Department of Germanic Languages at Columbia University. The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem is his third book on Yiddish literature.

His first book was based on his dissertation. Antonio’s Devils: Writers of the Jewish Enlightenment and the Birth of Modern Hebrew and Yiddish Literature (Stanford Studies in Jewish History and Culture) dealt with early figures in the development of modern Hebrew and Yiddish literature: philosopher Moses Mendelssohn (1729-1786), playwright Aaron Halle-Wolfssohn (1754-1835), and satirist Joseph Perl (1773-1839). The last is now credited with authoring the “first Hebrew novel” Megalleh T’mirim(Revealer of Secrets), an epistolary lampoon of the Hasidic sect. In the Demon’s Bedroom: Yiddish Literature and the Early Modern, (Yale University Press) reaches even further back in time to research premodern Yiddish writing from the 16th and 17th centuries.

Both of these monographs were published by academic presses; the book under discussion is published by Schocken, now a division of Random House, but a division that continues its original undertaking of developing Jewish literary works. This is Dauber’s crossover work; it is written in a style meant to appeal to a broader audience. While it includes the scholarly apparatus of footnotes, they are relegated to the back of the book, listed only by a phrase, thus leaving the public readership unencumbered by the pesky footnotes in superscript. The loss to the serious researcher is a certain precision in the footnotes, as well as the lack of bibliography.

The book itself is organized into five acts and multiple chapters (scenes?) with long chapter titles, as if a hybrid of a novel and a play by Sholem Aleichem. Although the writer’s greatest success was with the short story, this gesturing to the longer genres makes sense in light of Dauber’s assertion that “his life was his best performance” and the subject’s own statement that “a man’s life [is] the finest novel.”

Sholem Aleichem was the pen name and persona for Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich (1859 Pereyaslav-1915 New York). With Sholem Yankev Abramovitsch (1836- 1917 also known as Mendele Mocher Sforim or Mendele the bookseller, his creation, penname, and alter ego) and I. L. Peretz (1852 –1915), they are considered the three founding fathers of modern Yiddish literature. Rabinovich helped continue both Abramovitsch’s popularizing the literature, and Peretz’s raising its literary quality. He wrote prolifically, and founded several publications to create venues for the publication of more Yiddish writing. The book does note connections among them, as well as make references to other writers, but it is not meant to be a history of modern Yiddish literature.

Dauber makes a deliberate choice of referring to the subject of his biography, Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich, by his pen name and persona, Sholem Aleichem, throughout the study, as if his life and output were inseparable. It is almost as if one were to conflate Don Novello with Lazlo Toth, or Stephen Colbert the person with Stephen Colbert the persona.[i] Dauber explains his reasoning by the process of elimination and promises to be clear regarding whether he refers to person or persona in what follows. His dismissal of the currently accepted patronym (Rabinovich) as being unfamiliar and pedantic is not entirely convincing, but does suggest that in straddling the academic and popular audiences, he favors the latter.

His choice is especially curious in light of his efforts to add depth and dimension to our understanding of the earlier writer’s work, and puts the reviewer uncomfortable with the decision in a difficult position. For who wants to be considered pedantic in any context involving the inimitable Sholem Aleichem?

The pen name, as has been explained many times over, is a greeting that literally translates to “may peace be upon you (plural).” Yiddish scholar David Roskies refers to the writer more colloquially as “Mr. How Do You Do.” [ii]

At the outset it needs to be stated that Dauber obviously knows his subject very well, having read as much by him and about him as any other scholar. Clearly immersed in the writings of and research on his subject, he has written a very thorough study of a significant figure in Jewish literature, full of details and depth.

The task to write such is a book is daunting as much because Sholem Aleichem was such a voluminous writer, as because of the seemingly deliberate confusion and conflation between the biographical person and his persona. While Dauber seems cognizant of the dangers of reading too much biography into a person’s literature—and especially in the case of his subject – he is still tempted by the reader’s urge to read autobiographically. “[A] story he wrote,” suggests Dauber, “might shed some light on his ”

Dauber’s project is to reclaim his subject from his afterlife of nostalgia and sentimentality, a popular reading that flattens and minimizes the writer’s ostensibly greater, more complex, even messy, contribution to Jewish letters. The title of Dauber’s book is a play on the earlier central work on the writer, Maurice Samuel’s The World of Sholom Aleichem (1943). Samuel’s book was a celebration of Sholom Aleichem’s fictional characters and the environment in which they lived, examining the eponymous world from within. It was never meant to be a scholarly work, but serves as homage to the writer. Dauber’s book aspires to serve as a corrective to Samuel’s, and those of others, combining a discussion of the writer’s life with the world(s) created in his works, in addition to literary assessment, interpretation and reception. This would be an overwhelming charge for anyone of fainter-heart.

The Worlds of Sholem Aleichem include discussions of the larger contexts of the author’s oeuvre: the ways in which times were changing for the Jews of Eastern Europe from outside—the Enlightenment, emancipation and nationalist movements—and the inside—Haskalah, secularism, etc.; as well as the related language wars, mass immigration, the promise of America, and the challenge of Palestine/Israel. Dauber’s book is especially valuable in layering the multiple contexts and backgrounds.

Dauber also weaves in the story of the author’s life, from the multiple tragedies of deaths in the family, to financial struggles, and pogroms, as well as disastrous contractual arrangements, personal insecurities, and difficult publishing environments. He claims that the man remained optimistic at all times, but there are moments, especially when Sholem Aleichem seems overcome by self-doubt, that the cheerfulness seems to be a rather fragile veneer.

Chapter Two, Biography: In which we discuss recurring themes in the book, and in the life of its subject

“But his life was his writing”

Sholem Aleichem, was in many ways, the perfect chronicler for his stories. He had grown up both rich and poor, in town and in the shtetl, in an observant household and schooled in the traditional mode, but he had also been exposed to the Jewish enlightenment and educated in secular areas as well. The drama of his life gets diluted in all of its details, and Dauber’s fidelity to these details makes for some repetitive reading. While remaining true to the Yiddish writer’s biography, it is at the expense of a smooth narrative arc, favoring the trees over the forest. We do not get much in the way of relational history—for example, there are hints of a troubled father-son relationship, but no elaboration—yet the writer’s multiple successes and failures could emotionally exhaust the reader. His many peregrinations throughout Europe, to and from America, may leave the geographically–challenged lost in Nervi. But we soon find in the press of detail and information the presence of several recurring themes.

The first of these themes is that of money. Dauber shows that Sholem Aleichem suffered through a number of financial reversals, some of which were his own making, some of others, and some due to bad luck. He was often worried about supporting his family. The pattern began when he was a child, and his rich merchant father went bankrupt. Fortuitously marrying into a wealthy family was only a temporary fix; so too, his commercial successes. The anxiety about money fed into anxiety about publication. He was seemingly preoccupied with questions of venue—where to publish, whether to publish in a popular journal, or one that paid well, whom to alienate, and which readership to develop. He exhibited anxiety regarding the power and potency of literature, and his critical acclaim and legacy, all the while thirsty for adulation, and frustrated by not having greater visibility. His relationships with other writers, the petty feuds and rivalries and occasional reconciliations, the generosity toward and from others, are connected to his worries regarding his position and legacy.

Dauber makes a deliberate choice of referring to the subject of his biography, Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich, by his pen name and persona, Sholem Aleichem, throughout the study, as if his life and output were inseparable. It is almost as if one were to conflate Don Novello with Lazlo Toth, or Stephen Colbert the person with Stephen Colbert the persona.

With all his successes, he faced uncertainties, impossibilities and futilities. His many dislocations, repeated illnesses, encounters with official anti-Semitism including limits on travel, study, publications and freedom of speech, contributed to a general feeling of unease, an inability to be totally at home in the world.

This last trope of censorship—and the ways in which he was either thwarted by censorship, or managed to elude its grasp—belongs also to the theme of Sholem Aleichem’s engagement with broader culture that Dauber develops, with literature in Russian, in Hebrew, and in other (European) languages. The question of language, of course, is at the heart of every Yiddishist. Today it seems ironic, at least to me, that many Yiddish writers then turned to the language—from Hebrew – in order to reach a larger audience. The study notes that Yiddish was seen at the time as more affective, less prestigious, more popular, less artistically developed yet more deeply linked to Jewish culture than Hebrew. Sholem Aleichem tried to shape the language to be more literary.

Sholem Aleichem, like Mendele Mocher Hasforim before him, and I. L. Peretz, began writing in Hebrew. It was only by chance he turned to Yiddish, yet his early writings in Hebrew—and Russian—remain outside the purview of this study. He spent several formative years in Odessa, the capital of Jewish culture at the turn of the century. As scholars of Hebrew literature and Zionist history know, Odessa was the center for the early Zionist movement of Hibbat Zion, of Ahad HaAm’s Bnei Moshe Society for intellectual activists, and of Jewish literary activity. A number of literary publications and publishing houses were established in Odessa, many of which were committed, like Sholem Aleichem, to raising literary standards. The cafes were meeting grounds for the writers, editors, and publishers in both Hebrew and Yiddish. Dauber notes that in Odessa Sholem Aleichem found literary companionship—including a rivalry with Peretz and a reconciliation with Mordkhe Spektor—composed the popular lullabye “Sleep my child;” and created his first major character Menakhem Mendl.

Chapter Three, The Works: In which we attempt to summarize the writings of Sholem Aleichem

Life is a dream for the wise, a game for the fool, a comedy for the rich, a tragedy for the poor.

No matter how bad things get, you’ve got to go on living, even if it kills you.

One way to try to encapsulate the abundant writings of Sholem Aleichem is to divide them into genres: monologues, narratives of childhood, Jewish holiday stories, and village tales. Another is to review his main characters who helped establish his reputation and to whom the writer would return to more than once: Menakhem Mendl, Tevye, Motl the cantor’s son, and Kasrilevke, the quintessential Jewish village, which some have compared to Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County. Menakhem Mendl was a “homo economicus,” a spectacularly unsuccessful speculator, introduced in an epistolary novel that reads much like a forerunner to the television sitcom. His character spoke to both the opportunities granted by the spreading of capitalism, and the dangers, through a series of letters written home to his wife. He was perhaps the most autobiographical of Sholem Aleichem’s characters, though made into a caricature through exaggeration and repetition.

Tevye, the milkman, was inspired by a real person from the village where the writer spent the summer with his family. He developed the dairyman’s ability as a raconteur, and ratcheting up the man’s modesty and verbosity, created an idiom of self-effacement, suspect attributions, and scriptural mistranslations. The last element is a source for much of the humor, humor that helps the characters and their readers alike cope with the tragic. Although other studies have covered this ground, it would have added more color to the book to have expanded the discussion on the use and misuse of Jewish sources. The misattributions combine the high and low, simultaneously gesturing toward the innate wisdom of the simple folk, and the pervasiveness of Jewish learning. They add texture to the narrative, and reward the educated reader. There is also the element of slyness: perhaps Tevye is not that foolish after all.

The third character, the cantor’s son, represents the writer’s fondness for writing about childhood. Motl is a high-spirited prankster who emigrates to America with his family after having lost his father at a young age. Rather than a tragic figure, he feels lucky to be an orphan, for he is still protected by his older brother and mother, but not restrained by his father’s profession.

At the heart of all of these works were the changing times, the gap between generations, the intrusion of the modern. While change was seen as inevitable, it was not necessarily taken as progress. Even while Sholem Aleichem’s writings were so firmly rooted in a specific time and place, Tevye’s bewilderment as a parent toward his daughters becomes a universal for readers and audiences to relate to a century later.

Sholem Aleichem was more than industrious; he was, at least figuratively, to use Dauber’s categorization, a graphomaniac. As a small child he wrote on walls Dauber tells us; as an adult he wrote even when ill, and even against doctor’s orders. He wrote about the world of the shtetl, small almost hermetically sealed European communities of Jews, in which tradition reigned, and the outside world was just beginning to loom on the threshold. His style was postmodernist in that anachronistic way of Cervantes, Sterne, and others. He played with different levels of narration, of fictional methods and myth-making, and of self-reference .

His writing is more complex than what the reader initially notes. The mimetic realist style hides its craft. Sholem Aleichem is a master at playing high and low brow against each other, and light against dark; the dangers of illness, suffering, and death lurking under the bright shiny surface in a chiaroscuro painting of everyday life in the Jewish shtetl.

Much like Chagall, the writer often uses Yiddish sayings in their literal sense. For example, Dauber points out that Tevye, the milkman, was initially described as the father of seven daughters. Seven, because as it is said: Zibn tekhter is keyn gelekhter—“seven daughters is no laughing matter.”

But it is his use of the monologue, combined with the invention of the fictive listener, I would argue, that is the most memorable aspect of the Sholem Aleichem’s stories, and a reason for continuing to read him today.

Chapter Four, Authenticity: In which we get the heart of Dauber’s argument

You can take a Jew out of a shtetl, but you cannot take a shtetl out of a Jew.

With the book under discussion, Dauber joins a number of contemporary scholars—most of the major figures in Yiddish studies—who have written serious studies of Sholem Aleichem: Dan Miron, Ruth Wisse, Anita Norich, Ken Frieden, Hana Wirth-Nesher, as well as the aforementioned David Roskies. They have shifted the research from the biographical and philological (not to mention positivist-historical and Marxist) to one of style and influence.

When it comes to discussing specific works, Dauber shows himself to be gifted at interpreting literature. Sholem Aleichem, however, wrote many works, so there is never enough space to continue the literary analysis. More literary analysis might help the researcher with his question of the writer’s legacy, but the book’s multiple missions do not allow him to linger too long on any one text.

Dauber rightly claims the writer’s contemporary and lasting popularity, but does not entirely explain why. As Ken Frieden notes “But even in his prime Tevye was out of date.”[iii] Why then, do we continue to grant the writer a significant role in the history of modern Yiddish literature? The study tends to assume the reader’s agreement, if not knowledge, as it avoids directly articulating both his subject’s popularity and importance. It notes the Sholem Aleichem’s roles as writer, editor, and publisher in raising both the profile and quality of Yiddish literature.

Following Uriel Weinreich and Irving Howe (not to mention the Commentary contributor Midge Decter), before him, Dauber criticizes the sentimental-nostalgic nature of much of Sholem Aleichem’s posthumous reading. Focusing on the question of authenticity—without clearly defining his use of the term—he judges “Fiddler on the Roof” to be more of an “authentic expression of the midcentury Broadway musical than of the actual world of the actual Sholem Aleichem.” For a work that succeeds so well in describing the political and historical contexts of the author’s world, implicitly arguing that an artistic work is a product of its time, the assertion makes sense, but is hardly revelatory. And even while arguing what may be a given, at least among the academic sector of his audience, it does raise the question of which actual world and which actual Sholem Aleichem.

Dauber criticizes another production, “The World of Sholem Aleichem“ (1953), for combining material from other Yiddish writers (the aforementioned S. Y. Abramovitsch & I. L. Peretz) and traditions (the village of Chelm) and seems to use this as evidence for his claim of misreading. Yet Peretz, and Abramovitsch both wrote about the same milieu—the vanished world of Eastern European Jewry—as did Sholem Aleichem, and thus, their stories are, if not set in the same fictional world, of the same cultural environment and sensibility.

The scholar does, however, make a strong point, arguing that turning the Yiddish writer’s words into a Jewish folkdrama diminishes his achievements. The question is what can be done about this. And whether acknowledging Sholem Aleichem as “the man who created Tevye” in the subtitle of the work undermines the project of the book, or is a nod to the inevitable.

Sholem Aleichem was known as the “Jewish Mark Twain” in his lifetime.[iv] Dauber leaves the term standing, without questioning its reductionist effect. Wikipedia explains that it is because of “similar writing styles” and that they both used pen names. The internet entry does not speak to their shared sensibilities, humor, and popularity. A major difference between Clemens and Rabinovich, however, is that Sholem Aleichem was documenting a vanishing world, and was driven by fear and anxiety about its prospect for continuity.

Just a couple of years ago, Alan Mintz referred to Sayed Kashua, the Hebrew novelist and columnist as “Israel’s Arab Sholem Aleichem.” The article refers to the narrator’s “garrulous persona” and the “chatty,” “homecooked,” and artless style. The three—Mark Twain, Sholem Aleichem, and Sayed Kashua—all eschew elitism, hide the craft, and employ humor in their writing. Only Sholem Aleichem, however, does so in an endangered language.

Chapter Five Legacy: In which we try to assess Sholem Aleichem’s legacy and add our musings on the current status of Yiddish literature

This is an ugly and mean world, and only to spit it we mustn’t weep. If you want to know, this is the constant source of my good spirit, of my humor. Not to cry, out of spite, only to laugh out of spite, only to laugh.

Ironies and coincidences that abound in Sholem Aleichem’s writing find reflection outside of it. The apartment that he rents with his family in Lemberg is actually owned by a member of the secret police ; he once stayed in the same place as Charles Dickens; his hometown now has a museum dedicated to him and one to “Cossack Glory.”[v] And another. Just as I finished reading Dauber’s book, and turned on the news, African American actress and activist Ruby Dee’s death was announced. She had performed in the 1953 production of “The World of Sholom Aleichem,” in an unusual bit of colorblind casting. Just one more. I write this in a (very) small hotel room near the center of Tel Aviv; the cross street is none other than Sholem Aleichem Street.

Sholem Aleichem indisputably contributed to the golden age of modern Yiddish literature in a major way. But what does it mean for a writer to have contributed to a literature that is no longer flourishing, but is, in effect, dying? What does it mean to be a major figure in a very minor literature?

Odessa can be seen as the crossroads in the history of modern Jewish literature. While Mendele Mocher Sforim, Peretz, and Sholem Aleichem made their names in Yiddish, a lively, but hardly literary language, others were choosing Hebrew, a language which presented different and arguably greater challenges to writer. Many of the writers from that era we know today shifted between the two; those who chose Yiddish have an ever dwindling audience.

The choice between Hebrew and Yiddish has been explored in a number of forums, including Naomi Seidman’s A Marriage Made in Heaven: The Sexual Politics of Hebrew and Yiddish ( University of California Press, 1997); Yael Feldman, Modernism and Cultural Transfer: Gabriel Preil and the Tradition of Jewish Literary Bilingualism( Hebrew Union College Press, 1986); and the recent collection edited by Shiri Goren, Hannah Pressman and Lara Rabinovitch, Choosing Yiddish: Studies on Yiddish Literature, Culture, and History, ( Wayne State University, 2012). Even while there are glimmers of a renaissance in Yiddish—the success of the National Yiddish Book Center, a proliferation of academic programs in Yiddish studies in the US, Israel, and elsewhere, an Israeli theater production of Stempenyu,[vi] the establishment of a Yiddish kanguage-only farm in Goshen, New York—it hard to imagine another golden age of Yiddish literature. [vii]

A short story published 60 years after the death of Rabinovich, “Speak to the Wind”[viii] narrates a chapter in the competition between Hebrew and Yiddish. The protagonist Amos reluctantly pays a visit to a friend and rival of his father; the father is a Hebrew writer in Israel; the friend a Yiddish writer in New York. The visit is as awkward as the son imagined for many reasons, not least of which is the underlying tension inherent in the choice between Hebrew and Yiddish and their adherents. At the end of the story, the Yiddish writer calls the son’s attention to the building across the street, where it slowly becomes clear that it is a women’s prison. Men stand outside the wall, shouting to the women straining at the windows, sending legal advice in Yiddish. The New York writer’s delight is even greater when the Irish cop turns to them and asks, ”Who does he think he’s kidding, the gonif?” Thus, the story suggests that Yiddish continues to be a vibrant, relevant language, and has thwarted the Zionist upstart. The irony—an irony not unlike that often employed by Sholem Aleichem—is that the story itself was written in Hebrew.

What is Sholem Aleichem’s legacy if his influence can only be passed down in translation? While Tevye lives on, whether as an iconic American musical or the symbol of the loving father in an increasingly perplexing modern world, his Yiddish is relegated to an aging population of East European Jews, old socialists, and a small group of academics. Yiddish is truly thriving only among the ultraorthodox communities of Borough Park and Bnei Brak, with a much less rich jargon, limited by the lifestyles of the religiously observant. The language has become a pale shadow or a negative of itself, now closed from the outside world, from secularism, modernism, and change.