I do not remember when I first saw Roz Chast’s work. Sometime in the 1980s, I am guessing? I do not recall where I saw it, either—maybe in The New Yorker, possibly in a friend’s copy of one of Chast’s books. My recollection is faulty not because her work is not memorable—her cartoons are, for my money, some of the funniest around—but because of what makes it so wonderful: that the laughter it inspires feels like the laughter of recognition, as if her frumpy people and nutball captions had sprung from some dark corner of our brains, the part that looks askance at everything our conscious minds take for granted. Why, for example, is someone “dressed to the nines”? What if the person were (to quote one cartoon) dressed to the sixes? Or dressed to x, the unknown? Her cartoons, in other words, seem to be the expression of one’s own inner subversiveness, to have come from oneself, and that is what causes memory to fail. Do you remember meeting you?

The “dressed to the sixes” cartoon is an example of something else, too. Chast is the enemy of the grandiose, the sensational, anything that purports to involve more excitement or glamour than most of us ever experience, and her cartoons knock such things—hip fashions, trendy magazines—down to the level of our small, sad lives. There is, for example, the one captioned “Donna Karan’s Nightmare” (reprinted in Chast’s collection Theories of Everything, Bloomsbury, 2006, as are the other cartoons referenced below), showing an overweight woman with big blond hair and eyes caked with makeup, wearing a T-shirt that reads, “DKNJ.” Or this one: “Unattractive-length skirt: Scientists in our lab have worked for years to determine exactly the most repellent length for a skirt—and here it is!” This does not make Chast a champion of the people. She would be like Robin Hood, if Robin Hood stole from the rich and then said to the poor, “Ha ha, bet you wish you could have this!” What saves it all, what makes it funny and not mean, is that we sense she is laughing at herself, too. She may not be our champion, exactly, but she is one of us. How else could she get it so right? It would take one who has spent time mired in the quotidian and the petty to give us “Special Cards for Special Friends,” one of which reads on the inside, “You’re never in a crappy mood / You always buy organic food / Your family is smart and nice / You always give me good advice / Yet every time that we converse / I always feel a little worse—Why IS that, I wonder?” Or to give us “The Vain But Realistic Queen,” who says, gazing at her reflection, “Mirror, mirror, on the wall, Who, if she lost ten pounds and had her eyes and her neck done, and had the right haircut, could, in her age group, be the fairest one of all?”

Chast’s cartoons seem to be the expression of one’s own inner subversiveness, to have come from oneself, and that is what causes memory to fail. Do you remember meeting you?

Then there are her drawings of people, often middle-aged, uniformly unattractive, their facial expressions simply rendered yet managing to evoke bewilderment, or horror, or cluelessness—people you might pity if you could stop laughing long enough.

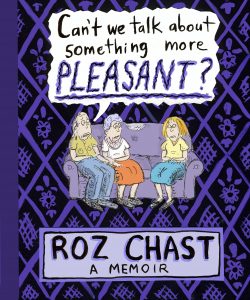

Comedy, like the blues, is often about relieving pain, converting into art those parts of life that would otherwise be unbearable. It is not a revelation at this point that the roots of humor are often dark. And so it should not be a surprise that Chast’s illustrated memoir, Can’t We Talk About Something More PLEASANT?, while frequently hilarious, is also undeniably grim.

Yet it is a surprise. The magic trick that Chast performs in her cartoons is to make laughter out of the dirty secret of life: it is an alternately stressful and humdrum affair, and then it is over. The reader might expect Chast to pull off that same trick with the facts of her own life, except that she has taken on an aspect of it that resists such treatment: her parents’ old age, decline, and death.

George and Elizabeth Chast were born less than two weeks apart, in 1912, and grew up two blocks from each other, in New York City’s East Harlem. “They never dated, much less anything else’d, anyone besides each other,” Chast writes. Their only child (other than the baby girl who died the day after her birth, in 1940) was born in 1954 and raised in an apartment in Brooklyn, where her parents continued to live until they could no longer take care of themselves. Chast glides past her own childhood, pointing to it just long enough to note its unhappiness: “I LOATHED Brooklyn. … The neighborhood was depressing, their apartment was depressing. Who needed it?” (Her illustration of her neighborhood, meanwhile, is very funny, with store names including “Smelly Old Groceries” and “Grim Dress Shoppe.”) As a single, small panel on the same page makes clear, she spent most of her childhood worrying: “I had no nostalgia for the Carefree Days of Youth, because I never had them.” Small wonder, then, that she left as soon as she could, living in Manhattan before moving with her husband and soon-to-be-born child to the Connecticut suburbs. From 1990 to 2001, she tells us, she did not go to Brooklyn a single time. Then she felt a sudden, “intense need” to visit her 89-year-old parents. She went to see them in their apartment, her childhood home, two days before 9/11.

For the next several years, Chast made regular visits to her parents, who, while growing more and more frail and living in increasingly grimy surroundings—which her mother would never have tolerated during Chast’s childhood—appeared to be more or less okay. Then came the inevitable: her mother’s fall, followed by her stay in the hospital with diverticulitis. During that time, Chast’s father stayed at her home, and it was then, observing the old man away from his wife and familiar surroundings, that Chast came to realize that senility had set in. After Elizabeth’s release from the hospital, both parents returned to the apartment, but it was not long before everyone involved acknowledged that that arrangement would not work any longer. Thus began the hugely exhausting, hugely expensive move to an assisted living facility, where the payout increased as the parents’ abilities diminished.

As Chast narrates and illustrates her parents’ travails, their personalities emerge. Elizabeth’s is, by far, the stronger of the two; Chast recalls that during her childhood, she and her father—whom she regarded as a kindred soul—would both occasionally cower before her mother’s rages. There was no question of rebellion on Chast’s part, because her mother was simply too much for her; there was only escape. George, by contrast, was a mild, kind man, though one with idiosyncrasies—such as an obsession with eating food slowly—that will reduce the reader to tears of laughter but must have sometimes been a source of plain old tears for Chast. George Chast adored his wife, happily deferring in matters great and small to what he felt was her superior judgment. And so, for all the kinship Chast felt with her father, her parents presented a united front, leaving Chast without an ally amid the outbursts, parsimony, and general smallness of life in that matriarchy. It makes perfect sense—and is very, very fortunate, for us and especially for Chast—that she found a creative outlet.

Having to take care of a parent means, on a fundamental emotional level, that life has turned upside-down, that you have only yourself to depend on in a world that has stopped making sense. Death, the thing that everyone sees coming and no one sees coming, the thing we creep closer toward one boring day, one stress-filled hour, one petty moment at a time, suddenly seems to be the only certainty in life.

One of the great strengths of this memoir is its honesty. Being responsible for the care of your elderly parents—even when, as in Chast’s case, they do not live with you—can be profoundly difficult for a host of reasons, not the least of which is disliking the person you sometimes become in the process. “I was not proud of my behavior,” Chast writes about a scene in which her father went into a fit of nervousness over nothing and Chast responded by shouting, “LISTEN: If you don’t pull yourself together, I am going to freak THE F—K OUT!” (Still: “He calmed down,” she notes.) Chast captures well the feelings of regret over errors of judgment, regret that can stay with you the rest of your days. “What could I possibly have been thinking?” Chast writes about her decision to leave her senile father and physically weak mother alone in their apartment on the mother’s first night out of the hospital.

Beyond that, and beyond the logistical hassles, stress, and sheer amount of time that goes into tending to your parents’ physical, legal, and financial needs, there is the existentialist angst triggered by it all. Having to take care of a parent (“the one who’s supposed to be taking care of you,” as Chast writes) means, on a fundamental emotional level, that life has turned upside-down, that you have only yourself to depend on in a world that has stopped making sense. Death, the thing that everyone sees coming and no one sees coming, the thing we creep closer toward one boring day, one stress-filled hour, one petty moment at a time, suddenly seems to be the only certainty in life. Chast does not come out and say any of this. She does not have to. The feeling permeates the book. The miracle is that there are genuinely funny moments amidst it all. Are there some things about the slow death of the very old that are actually inherently humorous? Or is it Chast’s special gift to interpret them that way? Whatever the answer, I found myself laughing out loud at this: “A couple of weeks into the around-the-clock care, hospice, etc. I went to see my mother at the Place, filled with dread, fearing the worst. Instead, she was sitting on the couch with one of the private nurses. … She was fully dressed. She was wearing shoes. She was eating a tuna sandwich. I knew that her retreat from the abyss should have filled me with joy, or at least relief. However, what I felt when I saw her was closer to: Where, in the Five Stages of Death, is EAT TUNA SANDWICH?!?!?”

Cartoonists have long amazed me, perhaps most of all because of what they do with people’s faces. For centuries, art historians have contemplated Mona Lisa’s smile, celebrating the human complexity it conveys and pondering what it reveals about her; but Da Vinci had paint and the illusion of three-dimensionality to work with, whereas Chast uses only lines, and precious few at that—and yet is able to portray not only simple emotions such as anger or fright but more complicated states of mind like bewilderment and relief, all, no less, with a comic edge. She can even do forced cheerfulness: “O.K., Mr. Hanratty!” says a nursing-home aide, “Time to change your Depends!”—the cheer of her broad smile belied by her dead eyes, which Chast masterfully represents by giving her two tiny dots for pupils.

Cartoons are by definition a hybrid form, combining drawings and words; Can’t We Talk About Something More PLEASANT?, unlike many graphic novels and memoirs, might be called a double-hybrid, interspersing cartoon panels with straight text that is printed in the same handwriting Chast’s fans have come to know and love over the decades. The effect is of reading not a memoir but a long letter from an old friend who likes to draw. This double-hybrid, with the panels driving home the points in the text—or does the text comment on the action in the panels?—has a deepening effect, like harmony in music.

The sensibility underlying Chast’s cartoons has always involved a tragicomic marveling at the mundaneness and worry—worry as unceasing as it is pointless—that makes up so much of life. To read Can’t We Talk About Something More PLEASANT? is to locate the source of that sensibility. Chast left the sad environment of her childhood, but it has never left her. It is deposited permanently in her psyche, generating interest in the form of her wonderful work, while the principal, for better or worse, for better and worse, is undiminished.