Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Broadway musical Hamilton has received overwhelming praise from reviewers, critics, and celebrities.[1] Hamilton has also received 11 Tony Awards and a Pulitzer Prize in drama, and its high-priced tickets are regularly sold out months in advance. Its upcoming tour is predicted by many to have similar success. In short, Hamilton’s champions argue that the musical offers a progressive revisionist history of the American Revolution and the founding of the nation through the eyes of its complicated protagonist, Alexander Hamilton, the Federalist architect of the American financial system. Much of this praise stems from Hamilton’s music, which relies heavily on rap and hip-hop, and its colorblind casting, in which people of color are cast in roles portraying white historical figures.[2]

Some critics have argued that Hamilton is not as progressive or revolutionary as many would think. For example, James McMaster wrote about the musical’s questionable feminism, its portrayal of Hamilton as an “exceptional” immigrant, and the potential for mostly white, upper-class audiences to feel racially progressive simply for having watched a cast of color perform. Gene Demby of NPR, Lyra Monteiro (in an interview with Slate), and Lucia Castaneda of F News Magazine have commented similarly, expressing discomfort with audiences’ limited access to the musical (primary demographics for most Broadway musicals, including pricey tickets for Hamilton, include predominantly white and upper middle-class groups), the fact that the musical is still about white Americans, even if it prominently features actors of color, and the lack of substantial plots for female characters.

Even as Miranda pushes against the values of traditional musical narratives by relying primarily on popular musical genres, he maintains the values that privilege musical complexity.

These critiques are not without merit. Still, Hamilton’s music and casting indeed complicate historical narratives that exclude people of color and their contributions, putting rap and hip hop and people of color at the center, rather than the fringes, of American history. As I argue, Miranda’s musical choices, particularly with regard to genre, reverse traditional accounts of musical history by focusing on values taken from popular music, rather than values from art music. However, the ways in which Miranda does so at times contributes to critiques that view Hamilton as a problematic example of a progressive historical narrative.

Traditional music historical narratives have tended to consider all classical music history on a single linear line, progressing from simple musical forms, harmonies, melodies, and rhythms, to music featuring greater complexity and “artistic value.” Similar narratives were subsequently mapped onto other musical genres. As jazz scholar Scott DeVeaux argues, broad acceptance of jazz into conversations of musical value came only when jazz’s history could mirror that of European music: “The fact that jazz could be configured so conventionally was taken by many as a reassuring sign that the tradition as a whole had attained a certain maturity and could now bear comparison with more established arts.”[3]

DeVeaux, and scholars after him, have critiqued jazz historical narratives with their roots in the mid-20th century as retaining “outmoded forms of thought.”[4] In particular, DeVeaux challenges the notion that “the progress of jazz as art necessitates increased distance from the popular.” In Hamilton, Miranda reverses the values of such musical histories, privileging popular music and positioning popular genres as representing not only artistic progress, but democratic values.

Hamilton features a variety of musical genres, from traditional Broadway show tunes to R&B, and from jazz to hip hop. Each character sings in a particular genre that provides the audience clues regarding that character’s position in the story. As Daveed Diggs (Lafayette/Thomas Jefferson) explained to PBS, “What Lin was able to do was create different styles for each character.”[5] While the part of Alexander Hamilton (Lin-Manuel Miranda) sings in several genres, in the moments in which he is an active politician—when he argues his stance to George Washington, Aaron Burr, or Thomas Jefferson, for example—Hamilton usually raps.

In Hamilton, Miranda reverses the values of such musical histories, privileging popular music and positioning popular genres as representing not only artistic progress, but democratic values. Hamilton features a variety of musical genres, from traditional Broadway show tunes to R&B, and from jazz to hip hop. Each character sings in a particular genre that provides the audience clues regarding that character’s position in the story.

Most of the other revolutionaries, including George Washington, Hercules Mulligan, Marquis de Lafayette, and John Laurens, also rap their political beliefs. Each has their own particular style; Diggs explains that “George Washington raps in this very, sort of, metronomic way, because that is similar to how he thinks—it’s all right on beat.”[6] Lafayette, on the other hand, comes from France, and “has to figure it out. Lafayette is rapping in a real, like, simple, sort of like early 80s rap cadence at first, and then by the end is doing these crazy double and triple time things.”

The transformation of Thomas Jefferson (Daveed Diggs) clearly demonstrates Miranda’s musical representation of American democracy through popular music in Hamilton. Jefferson makes his entrance to “What’d I Miss,” a Cab Calloway-styled jazz number complete with boogie-woogie bass line—the type of song that would have been popular in the 1930s and 1940s. The piece marks Jefferson’s return to the United States from a five-year post as ambassador to France. According to Diggs, “Thomas Jefferson has a lot to catch up on. So when we meet Jefferson, he’s still singing jazz songs, and the rest of the United States has moved on to rap music, and he doesn’t, he doesn’t know that. [laughs] Nobody told him!”[7] Throughout the musical, Jefferson is at times portrayed as an old-fashioned, slave-owning hypocrite, and his association with jazz, a once revolutionary and now completely mainstream, even elitist music, is representative of that image.

However, Jefferson adapts as quickly to rap as he does to the American political scene. The very next scene features the first rap battle, which pits Jefferson against the ostensible freestyle rapping of Hamilton. The Cabinet Battles are likely part of the reason critics point to Miranda’s use of rap and hip-hop as being particularly groundbreaking within a Broadway musical. These battles are styled after rap battles featuring freestyle rappers challenging each other to invent technically complex rhythms and rhymes, all the while bragging about themselves, their accomplishments, and their prowess. In rap battles, each rapper must convince the audience that they are the better rapper; Miranda uses this format to portray two politicians attempting to gain the votes needed to pass legislation. In “Cabinet Battle #1,” Jefferson begins his portion with fairly simple, one-syllable rhymes at the end of his lines (an AA rhyming scheme):

“Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,

We fought for these ideals, we shouldn’t settle for less.”

However, in the next two lines, Jefferson adds interior rhymes while maintaining rhymes at the end of the lines:

“These are wise words, enterprising men quote ’em

Don’t act surprised, you guys, cuz I wrote ’em.”

In what follows, Jefferson continues to place rhymes at the ends of phrases, but offers some variety. For example,

“Our debts are paid, I’m afraid

Don’t tax the South ‘cause we got it made in the shade.”

Hamilton, on the other hand, begins with two-syllable rhymes at the ends of his lines:

“Thomas, that was a real nice declaration.

Welcome to the present, we’re running a real nation.”

However, a few lines later, Hamilton expands the end of the line rhymes to three syllables:

“How do you not get it? If we’re aggressive and competitive

The union gets a boost. You’d rather give it a sedative?”

Following this section, Hamilton breaks up this pattern of end of the line rhymes with interior rhymes. By the end of Hamilton’s rap, he’s inserting interior three-syllable rhymes that match the end of the line rhymes in lengthy passages:

“Thomas Jefferson, always hesitant with the President

Reticent—there isn’t a plan he doesn’t jettison

Madison, you’re mad as a hatter, son, take your medicine

Damn, you’re in worse shape than the national debt is in.”

While Hamilton ultimately does not win this battle, the complexity of his cadence over that of Jefferson’s is clear. Importantly, even as Miranda pushes against the values of traditional musical narratives by relying primarily on popular musical genres, he maintains the values that privilege musical complexity. These values of complexity, however, are defined by the tenets of hip hop and rap through rhythm and flow, and not those of western classical music, which tend to privilege harmony and melody.

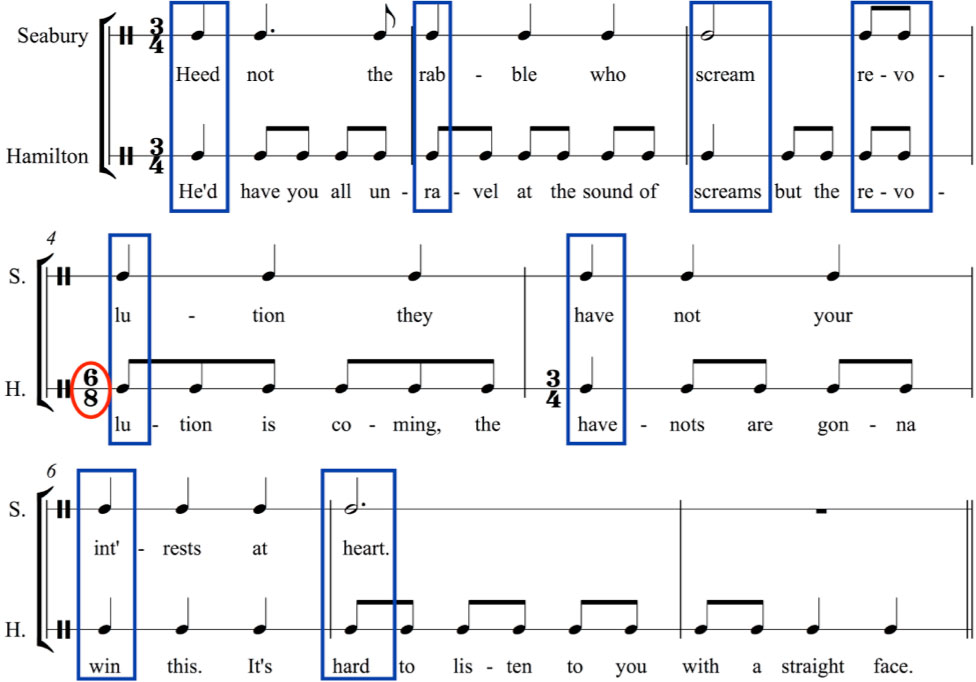

What Miranda values as musical complexity is perhaps demonstrated most clearly in “Farmer Refuted,” sung by loyalist Bishop Samuel Seabury (Thayne Jasperson), who voices his objections to the Continental Congress. The piece begins in a strict 3/4 meter; Seabury sings almost entirely in quarter notes, portraying a very strict sense of rhythm. The prominent harpsichord accompanying Seabury enhances the mechanical feel of the meticulous rhythm, and gives the number a distinctly outmoded flavor, especially in contrast to the other characters’ contemporary stylings. Hamilton eventually joins Seabury, refuting Seabury’s points, even as Seabury continues to make them. When Hamilton begins, the harpsichord is immediately replaced by a piano and strings.

In the transcription below, I have shown the points at which Hamilton’s improvised speech intersects with Seabury’s planned speech. Hamilton either speaks the same words as Seabury or closely rhymes with Seabury on every downbeat. Further, measure four shows a point of rhythmic complexity for Hamilton; while Seabury maintains his simple 3/4 meter in quarter notes, Hamilton transforms the measure into a compound 6/8 meter. The combination of Hamilton’s meter with Seabury’s creates a hemiola—a musical figure in which a triple feel is superimposed on a duple feel. Throughout their encounter, Hamilton interjects eighth-notes and triplets between Seabury’s slower-paced notes, ultimately transforming Seabury into a sputtering, whining mess.

Ex. 1, “Farmer Refuted,” shared verse between Samuel Seabury (Thayne Jasperson) and Alexander Hamilton (Lin-Manuel Miranda). Author’s transcription.

In Hamilton, black art is positioned as the powerhouse behind America’s burgeoning democracy, directly contrasting the stodgy, inaccessible, white European music of an elitist government that refuses to represent the whole of its kingdom.

That Hamilton, a Founding Father whose legacy continues to influence America’s government and financial system, is able to improvise complex double- and triple-time rhythms and rhymes to Seabury’s planned, excessively square speech demonstrates how Miranda confers value on popular music by framing complexity through techniques associated with hip hop and rap. This example is considerably more extreme than that of Thomas Jefferson’s jazz; while Jefferson eventually gains some proficiency in rapping, it is hard to imagine Seabury, so reliant on his written speech, gaining such fluency. Add to that that Seabury is one of few characters represented by a white actor, and the distance between the genres becomes even greater. In Hamilton, black art is positioned as the powerhouse behind America’s burgeoning democracy, directly contrasting the stodgy, inaccessible, white European music of an elitist government that refuses to represent the whole of its kingdom.

However, as a few critics have noted, Miranda’s portrayal of women in the musical largely does not contribute to this revisionist history. With the exception of Angelica Schuyler (Renée Elise Goldsberry), Hamilton’s women do not participate in rap—and none of them participate in the complex debates surrounding the Revolution and the formation of the American government. However, Angelica positions herself as a highly skilled rapper. Consider “The Schuyler Sisters,” in which Angelica and her sisters, Eliza (Phillipa Soo) and Peggy (Jasmine Cephas Jones), travel to New York City to stay with their aunt and uncle (and find husbands). This number serves as an introduction to the Schuyler sisters. Angelica immediately establishes herself as being dedicated to politics, which Miranda backs up by having her rap. Her rap includes three-syllable rhymes at the ends of lines, and also moves from an AABB rhyming pattern to an ABAB rhyming pattern.

Angelica:

“I’ve been reading Common Sense by Thomas Paine,

So men say that I’m intense or I’m insane.

You want a revolution? I want a revelation

So listen to my declaration:”

Angelica/Eliza/Peggy:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident

That all men are created equal”

Angelica:

“And when I meet Thomas Jefferson

I’m ‘a compel him to include women in the sequel!”

While Angelica Schuyler’s rap is indeed fast-paced and rhythmically complex, the rap genre and Miranda’s seeming ideal of musical complexity are nearly exclusively reserved for the musical’s men. Goldsberry explained in a PBS documentary that, “Lin actually credits Angelica with being the smartest person in the show. What she could do with her pen, what she could probably do with a look [chuckles], was very, very potent, and probably had to be.”[8] That Miranda thinks of Angelica as the most intelligent character in the show, combined with the fact that she is the only woman who raps in the show, problematically suggests that she is unique among women in terms of her intelligence, as well as her ability to and interest in engaging politically with men.

Aside from the Schuylers, the only other major female character is Maria Reynolds (Jasmine Cephas Jones), the woman with whom Hamilton has his infamous affair. As The New Yorker’s Michael Schulman explains, Reynolds “isn’t much more than an archetypal femme fatale—sort of a sultry Rihanna type—and, while the the show doesn’t let Hamilton off the hook, he comes across more as a dupe than as an adulterer.” Indeed, “Say No to This,” in which Reynolds seduces Hamilton as he asks how he could possibly say no to a romantic encounter with Reynolds, is a steamy R&B number complete with melismas and an emphasis on words with “ah” and “oh” vowels that evoke soft moans.

The fact that the women of Hamilton primarily sing either typical lyrical Broadway ballads or in R&B genres demonstrates a reliance on stereotypes that suggest women are inauthentic performers of rap—and, even more problematically, that they are inauthentic political thinkers.

Hamilton’s three main female characters each seem to exist for the purpose of drawing out some aspect of Hamilton himself—and this is born out in the musical genres in which each performs. Maria Reynolds’s R&B number exists primarily to demonstrate Hamilton’s sexuality, Angelica Schuyler’s ability to rap in “Satisfied,” shows off her intellect, which serves as a device to show Hamilton’s similar intellectual interests, and Eliza Schuyler Hamilton’s lyrical Broadway tunes like “Take a Break” and the upbeat R&B-influenced “Helpless” show off Hamilton’s care and concern for those close to him.

The fact that the women of Hamilton primarily sing either typical lyrical Broadway ballads or in R&B genres demonstrates a reliance on stereotypes that suggest women are inauthentic performers of rap—and, even more problematically, that they are inauthentic political thinkers. As McMaster writes, “One could rationalize Miranda’s gender-related creative choices with ye olde historical accuracy argument: ‘Well, this is just how things were back then! Can’t argue with history!’ But it’s hard to accept such an explanation when black and brown men populate the stage, a historically inaccurate depiction of our founding fathers.” Miranda demonstrates character development through rap in many of his male characters of color, with the significant exception of Seabury and King George III, both represented by white actors; it is striking that the few women of Hamilton receive no such development through musical genre and are nearly entirely excluded in rap performances. While Miranda’s revisionist history turns traditional musical historical values on their head by not only privileging popular music, but by allowing hip hop and rap to be valued in terms of rhythm and flow, his history is inclusive only for male characters; this leaves significant room for the development and growth of his female characters.