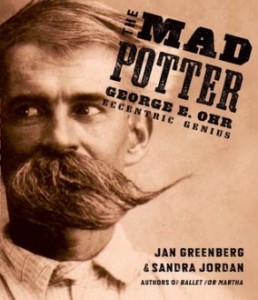

George Ohr’s mustache alone would make him an appealing subject for a children’s biography. It waves asymmetrically from the cover of The Mad Potter, testifying to the eccentricity promised in the subtitle. But there is more on offer: His “genius” is also persuasively displayed in the lustrous color photographs of his ceramics that appear throughout the text. This skillfully-managed combination makes the book a valuable contribution to the lively genre of juvenile biography, one that has become increasingly rich and diverse in the past decade. A glance at the holdings of any public library will reveal a generous selection of well-produced hardcovers whose subjects range from Benjamin Banneker to Beyoncé, from Julius Caesar to Julia Childs. Co-authors Jan Greenberg and Sandra Jordan have made their mark within this genre by concentrating on figures in the arts, producing works for young readers on Jackson Pollack, Vincent Van Gogh, and Martha Graham. By selecting George Ohr as the subject of their latest book, the authors add ceramic art to an award-winning body of work that has addressed painting, dance, musical composition, and art installation.

Born in Biloxi, Mississippi, in 1857, George Ohr spent almost three decades producing and creatively marketing his handcrafted “art” pottery; upon his retirement in 1910, he crated up some 5,000 of his pots and placed them in storage, ordering his family not to sell them for 50 years. While Ohr had difficulty finding buyers for his work during his lifetime, he remained confident of its value. Providing a sample of his work to a potters’ association for display, Ohr wrote, “I send you four pieces, but it is as easy to pass judgment on my productions from four pieces as it would be to take four lines from Shakespeare and guess the rest.” Greenberg and Jordan begin their narrative with the discovery of Ohr’s cache by an antiques dealer in 1968 and end it by describing the construction of a Gehry-designed museum for the display of Ohr’s work, thus validating Ohr’s assessment of his artistic accomplishment and providing a satisfying frame of reference for the reader.

The major episodes of Ohr’s life are well told, and the authors do not gloss over his struggles: in his early days, he had to peddle his wares from a push cart; later, both his house and his pottery were destroyed in one night in a downtown fire; toward the end of his career, a trip to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair proved so financially disastrous that he had to give pottery lessons in order to buy a return ticket to Biloxi. The authors’ prose style as they recount these events is direct, engaging, and fairly sophisticated for a children’s book (Ohr “concocted little tests” for his customers, the effect of his pots is “witty, rhythmic and sensual”). The text-to-image ratio is higher than that found in many hardcover juvenile biographies (Leonard Marcus’s recent book on Randolph Caldecott is another distinguished exception to the rule), and they have divided their text into chapters. While the authors’ website designates the intended audience range as 9-12, my impression is that the likely core readership for this work may be at the upper end of this range, easily including those in their early teens. Unfamiliar terms, often technical or historical, are gracefully and unobtrusively explained, often in appositive phrases, allowing for uninterrupted reading.

The book’s design is admirably tailored to its subject and purpose. In the authors’ previous book, Ballet for Martha, the text was accompanied by Brian Floca’s imaginative illustrations; here, instead of illustration, the authors employ photographs (along with a few contemporary prints and paintings) to add visual interest. A significant and complementary division emerges from this approach—the 19th-century black-and-white pictures offer a fascinating glimpse into the busy passage of Ohr’s daily life, while the 21st-century color pictures provide evidence of his enduring legacy. The two are woven together throughout the text, sometimes appearing on the same page. The older images are faded, yet cluttered and energetic: pots march along boards, dangle from the eaves of the workshop, and overflow the shelves; Ohr gestures to crooked signs that advertise his works in superlatives. In contrast, the modern images are clean and simple, allowing the reader to study the lines and colors of his work without distraction. The plain presentation—pots crisply outlined against solid-colored backgrounds—visually advances the argument that Ohr’s work transcends its 19th-century origin and instead participates in the aesthetic of the modern, making it appear, as the authors say, “fresh” and relevant in the 1970s, the era in which the pieces first began to appear at auction.

Another essential element of the book’s successful visual design is the use at key intervals of a playful, oversized typeface that echoes the appearance of 19th-century handbills and broadsides; in fact, it looks as if it could have been used by Ohr himself in some of his prolific self-promotional efforts. This typeface celebrates Ohr’s eccentric side, inviting the reader to appreciate his self-expression in media other than clay. For Ohr was a showman, a trick photographer, and a wit as well as an artist. He printed signs that he displayed around town, describing himself as the “’GREATEST’ ART POTTER ON EARTH.” He gave demonstrations at his wheel for tourists at what he humorously termed his “Pot-Ohr-E” (turning a single lump of clay into a succession of different objects) and experimented with the fantastical possibilities of photography (one shot shows him pouring a drink for his own mirror image). The unconventional typeface appears not only in chapter headings but also at unpredictable moments throughout the text, allowing an antique, handcrafted element to mingle with the book’s modern type. The effect is attention-getting and slightly “mad,” just as Ohr intended his own words to be.

The end result is a book that repays study at every level. The young reader can pore over its eclectic mix of visual attractions, starting with the front endpaper, which offers the opportunity to examine the faces of the Ohr family, including those of four children who appear to be planted in pots of various sizes. A small-print caption above a pitcher with a snake handle refers the reader, for comparison, to an earlier image of a serpent-wreathed jug by one of Ohr’s contemporaries. The pottery, of course, takes center stage throughout. Striated, desert-hued vases sit next to mottled green bowls, and the text encourages the reader to imagine how the vessels’ shapes were formed: “He might ruffle or flute the edges, twist the neck, [or] make a border of his thumbprints.” Alert readers will enjoy spotting individual pots that reappear at different points in the book. Special pages at the end of the book invite further kinds of active participation, explaining how to look at a pot and how to throw a pot on a wheel. This material, combined with a fuller account of the Biloxi museum dedicated to Ohr’s art, extends and broadens the reading experience and our understanding of Ohr’s story. Knowing that his work will indeed be discovered and appreciated, readers can accept the transformation of Ohr’s pottery into the “Ohr Boys Auto Repairing Shop” and enjoy a final image of the now-retired but still energetic Ohr in action: “His neighbors grew used to the sight of George, his long white beard flying in the wind, tearing down the beach on his motorcycle.” The figure of the artist remains one of engagement with the world, an engagement that is both displayed and encouraged by this creative, exuberant book.