We have a wider range of age groups in the modern workforce because we are living and working longer. As retirement ages increase, our workforce includes everyone from their teens to their 80s. Many businesses have five generations working together. This fact has not gone unnoticed by management consultants, theorists, and human resource professionals. Age bias, generational bias, and management literature all bend us to a belief that we should treat workers from different generations differently. A baby boomer wants a different reward than a millennial, we are told. Management style needs to take generation into account, it is said. Add to that a pervasive bias over the centuries that the next generation is going to “screw it up,” and you have age and generational bias and tension. But based on my 30-plus years leading and managing and being managed and led, this is all overstated. As we work through our life cycle, we are less influenced by our specific cohort, less likely to reflect characteristics of our historical generation, and more influenced by our age, other participants in our environment, our leaders, and our workplace culture.

Human beings engaged in the workforce by and large do not work in isolation and are not a “snap shot.” We grow and we age, influenced and shaped by leaders, co-workers, and corporate culture. We are affected by our personal lives at home. As a result, stereotyping workers and defining their needs, desires, and wants in the workplace based on when they were born, ignores the profound impact of other forces, debasing humans as much as any other arbitrary classification like race, gender, or religion. Leaders who would lead well must remember the person they seek to lead and manage is unique. The essence of great leadership is achieving this level of understanding.

The current generations

Gen Z is the newest generation to appear and encompasses those born after 2000. Millennials, also known as echo boomers or Generation Y, were born in the early to mid-1980s through the year 2000. Gen X is the generation that followed the boomers, so these folks were born between 1965 and the early 1980s. The boomers, the only group formally defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, were born between 1946 and 1964. Finally, someone born before 1946 is from the veterans or traditionalist generation. If you think traditionalists are too old to work, think again. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics there are about 3.67 million people employed who are 70 or older.

As we work through our life cycle, we are less influenced by our specific cohort, less likely to reflect characteristics of our historical generation, and more influenced by our age, other participants in our environment, our leaders, and our workplace culture.

If you look at actual employment status data, the three primary generations are fairly equally represented in the civilian labor force. The millennials represent nearly 50 million of the 149 million employed workforce, Generation Y nearly 49 million, and the boomers are about 47 million. Together these three groups represent about 146 million of the 157 million people in the workplace. The remainder consists of the 3.7 million over 70 years old, our traditionalists, and the rising Generation Z, which has entered the workforce with nearly 5.7 million people.

The case for treating the generations differently

One of the best and most often cited articles on leading and managing a multigenerational workforce was published by AARP, written primarily by Susan A. Murphy, PhD, of Claire Raines Associates. The AARP article defines the generations and describes the differences in their characteristics based on events that transpired in their collective formative years. As a result of these differences, the authors recommend methodologies for easing generational tension and leveraging generational diversity. There are one or two articles that take the opposing view. That is, they question, based on surveys of the generations, whether there are any differences at all between the generations with respect to their attitudes toward work and the workplace, and therefore, whether there should be any difference in how members of the different generations should be led and managed. There are plenty, for example, that seek to dispel common myths about millennials.

Leaders and coworkers, the effect of commingling

I began my career in 1985 right out of law school as a corporate lawyer for Union Pacific Railroad. My first boss was a veteran who fought at The Battle of The Bulge in 1944. He used to describe it to me; what it was like to be in the second wave of troops during that nearly month-long battle, describing combat in vivid terms. He shared with me that they had cleared the battlefield of American casualties, but left the Germans, and what a confidence boost that had been, not realizing at the time it was intentional. His management style was formal-militaristic, and work was serious. He was a classic traditionalist. And so, as a young person, early in my career, I adapted to his style. After all, he graded me. He decided whether I got raises. He decided what office I got. He decided what work I got. He decided whether to promote me. He shaped me quickly. Although 25, I became more serious and intense.

Leaders are powerful shapers. Other coworkers and peers can shape you as well, but leaders are the most powerful. Leaders control the rewards. Leaders control the punishments. If a leader reflects characteristics of a generation, you will pick up some of those traits and attitudes, even if you are not from the leader’s generation. If someone did not know my age, based upon how I approached work and the workplace under my first boss, they would have classified me as a traditionalist.

Workforce participants mostly do not work exclusively in a segmented layer of their age group, they “commingle.” We bounce off and scrape against leaders, peers, and subordinates of all different ages; and like molecules, the larger and more frequent the collisions, the greater the exchange of human material and the greater the change in behavior of the participants. We are constantly shaped by this commingling.

Cultural adaptation

Like powerful leaders, the organizational culture also shapes individual workforce participants, regardless of their generation. The organization, through its culture, provides the code of ethics of the organization and the unwritten rules of how decisions are made and what behavior is acceptable. The organization rewards and punishes its members to reinforce the culture. As the culture is reinforced, workforce participants adapt or they leave.

Three cultures I worked in show how culture shapes workforce participants, regardless of their generation: the culture of a 125-year-old multi-billion dollar company in the 1980s, the culture of a large law firm in Chicago in the ’90s, and a startup in the dot-com era in San Francisco. Each of these environments had members of multiple generations, but the culture reshaped the generational characteristics of all the participants.

125 year old multi-billion dollar company culture: The culture in the large, old corporation was conservative. Our job was to preserve assets and improve and maintain our market share. We did not take risks because we did not have to take chances. We were almost a government. We set the rules. Desks were numbered. Process and compliance were the lifeblood of daily work. Job evaluations were formal. Memos were sent with Mr. or Ms. before your name (mostly Mr. back then, I’m sorry to say). We filed into conferences in reverse order of seniority and left conferences in the opposite order, most senior first. If you broke one of the unwritten cultural rules, you found out quickly. You were socialized and retrained.

The theory that your generation and influences from your formative years would sustain your generational characteristics is simply that–a theory. The theory that workers from different generations do not change would be more accurate if you were only surrounded by your generation and gen-types and only worked in cultures reflecting your generation’s traits. But you are not, and you do not.

To get promoted in such an organization, someone had to die. Every person below the deceased worker was promoted and a new janitor was hired. There was no getting ahead unless someone left the workplace, and then everyone moved up a notch, including you.

Traditionalists ran the company, and if you were a boomer and idealist with creative thoughts or vision, you quickly learned to suppress those urges and remember your place. This culture changed how you viewed the workplace and how you viewed work. The theory that your generation and influences from your formative years would sustain your generational characteristics is simply that–a theory. The theory that workers from different generations do not change would be more accurate if you were only surrounded by your generation and gen-types and only worked in cultures reflecting your generation’s traits. But you are not, and you do not.

Large mid-western law firm: The culture in the large law firm was idealistic, smart, serious, and competitive. We worked hard. We worked around the clock. The more hours you billed the more rewards you got. If partners wanted something done well, it went to the best and busiest. It was Darwinian. If you fell behind, you were eventually not given work and had to leave.

It did not matter what generation you were from in the world of smart, serious, and competitive. We had at least three generations in that work environment. They all competed. Age did not matter except that, generally speaking, the associates in the firm were younger than the partners. But the partners competed with the associates. Boomers ran the firm and their hard work ethic showed. But traditionalists, boomers, and Gen X did not set their own culture due to their generational differences; they adapted to the culture of success and hard work of the firm. Or they left.

Startup environment in San Francisco: The culture in a startup is all about invention, innovation, and disruption. You pretend nobody has ever done or thought about doing what you want to do. Experience did not matter; in fact it was a perceived negative. It gave you bias and hindered your creativity. Startup environments are endless hours of work and interaction with intermittent, almost silly fun blended into the hours. The goal is creativity so activities are designed to spark it and make you feel special and brilliant.

We had all four generations in our startup. People adapted no matter what demographic they hailed from. You were a traditionalist and valued experience? Get over yourself. Work was fun, exploratory, and zany. We had a traditionalist from IBM as an employee. He was eating candy and snacks and coding and joking. He became a seamless member of the team, affected and reshaped by the culture.

Transference

There was a Harvard Business School case study about transference, which I read as a young MBA student. Transference is a complicated psychological phenomenon and theory about the redirection of feelings from one person to another, often from some childhood feeling or relationship to another later in life. The article made us aware, among other factors, that how we were with authority in our family would be reflected in the workplace. As an example, children who grew up in larger families were more likely to function well in teams at work. Middle children were supposedly better at negotiating and multifunctional teams, as they were always in the middle of their older and younger siblings. If you fought with your sister at home, you were more likely to have conflict with your female coworkers. “First borns” were supposed to be natural leaders. In fact, 21 of the first 22 astronauts were first-born children.

The existence of transference of your attitudes toward family members or others in your personal life is not affected by your generation. We all do it. But what that transference looks like could well be affected by your generation, because transference will change as basic relationships, like societal norms in family relationships, change. Views towards authority, for example, will change and have changed as family structures have changed over the years. Those of us who were raised as boomers or traditionalists may have come from strong patriarchal families, thereby influencing our view of authority in the workplace. In other words, we accepted and maybe came to desire hierarchal authority. Leaders could count on respect for authority because “Father Knew Best” at home. Fear of punishment by authority figures in our personal lives (“Wait until your father gets home!”) led to corporate discipline in the workplace.

On the one hand, older workers are seeking and are comfortable with hierarchal structures, and on the other hand younger workers want teams and peer structures. This is a paradox of modern leadership.

But family structures changed as mothers went to work and divorce rates climbed. As a result of single-parent family structures and dual working parents in newer family structures, older siblings became more influential. Recent work and research finds millennials looking to siblings more for authority, and leadership and enjoying working in peer-to-peer environments. As a result, strong patriarchal leadership with millennials may not be as effective, and may even backfire.

Coupling the tiers of demographics in the workplace with transference leaves leaders with a tremendous challenge. On the one hand, older workers are seeking and are comfortable with hierarchal structures, and on the other hand younger workers want teams and peer structures. This is a paradox of modern leadership. Leaders are faced with providing a different leadership style for different generational participants in the workforce. How do you do this with a team with multigenerational participants?

The natural life and work cycle

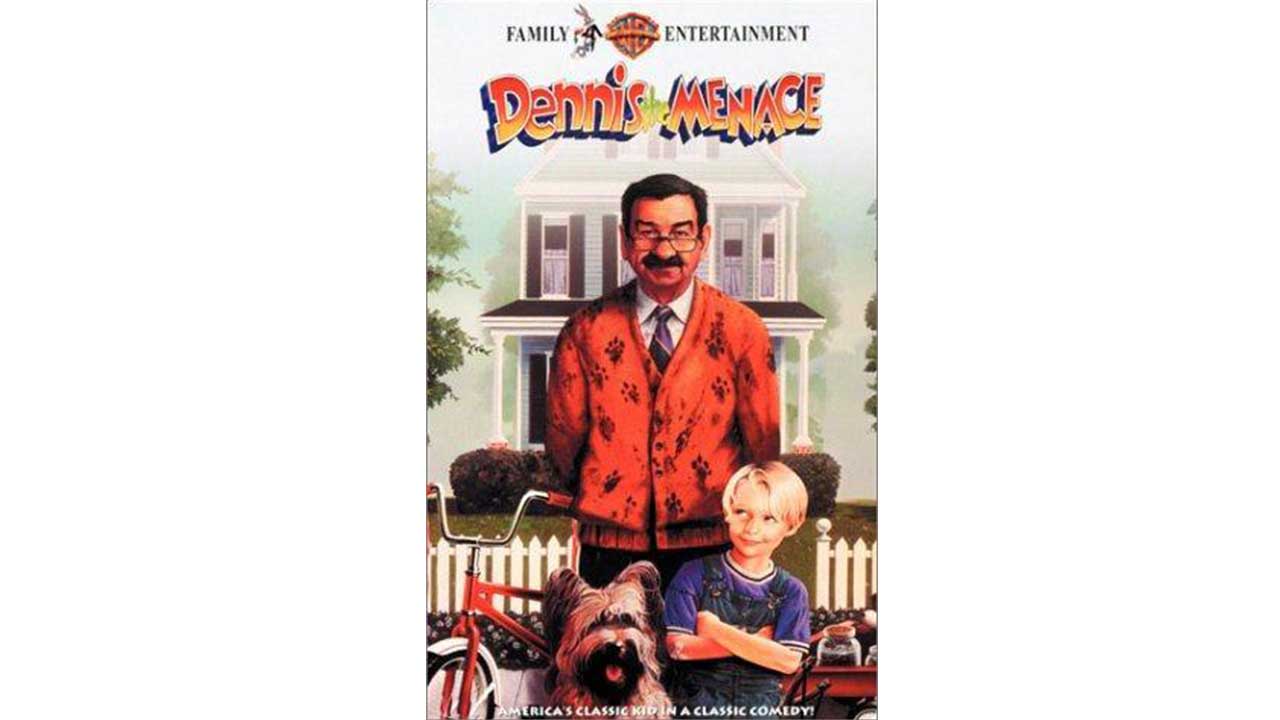

In the interest of full disclosure, I confess to being a boomer. Like most of my generation I grew up on evening family television–black and white early on, and finally we got a color TV. I have fond memories of watching Gilligan’s Island (1964-1967), the Dick Van Dyke Show (1960-1966), and Dennis the Menace (1959-1963), all in black and white. Dennis the Menace was also a long running comic strip that first appeared in 1951 and runs to this day. I suppose I identified with 5-and-a-half-year-old Dennis who loved to experiment, was well meaning, but also tended to get in trouble; not bad trouble, just unfortunate trouble. Dennis had an older, grumpy neighbor, Mr. Wilson. Dennis may have thought of himself as Mr. Wilson’s best friend, but in fact he was Mr. Wilson’s nuisance. My memories of Mr. Wilson are not fond. He was the mean old guy in the neighborhood. I certainly did not understand him.

I spent the first 50 years of my life in various suburbs in the U.S. like the one in which Dennis lived. Eventually our kids graduated and went off to college. The homes in our neighborhood in suburban Dallas “turned over” to new families with young children. One day some kids rang my doorbell and ran. Another day my house got teepeed in toilet paper. I saw kids pointing at me and plotting pranks. I got mad about all the nuisances and tricks. I looked at them look at me and then it hit me: I was Mr. Wilson. I had become the old neighbor in the ’hood. I had become the old man I could not understand. Except now I understood him. Mr. Wilson was just a guy next door whose kids had grown up and moved on in life.

The conflict between Dennis and Mr. Wilson related to age and where they were in life. The kids in my neighborhood did not target me because I was a baby boomer; they targeted me because I was old and did not have kids at home for them to play with. And I was crusty. They were carefree. They were kids.

In the workplace, when we are new and we are young, we bring our millennial game. We come hopeful. We come excited. We come seeking opportunity. We yearn for training. We think it is all about us. As we get older we look for different things. After conflict with a boss or coworker we may become skeptical and after many years we may seek meaning.

The multigenerational leadership challenge

The extension of life expectancy is leading to work environments with participants across the age spectrum. Five generations of participants in one work environment is now the norm. And as a result of transference, the metamorphosis of family structures has changed the type of leadership and authority younger generation workers want. These changes place great stress on those who would attempt a single style of leadership. What is a leader to do?

First and foremost, as is generally true of great leaders, they need to know their own bias, including their generational bias. If you are a traditionalist, you may overemphasize experience and discipline. If you are a millennial, you may lack respect for process and experience. Being aware of your own bias and where you are in the work life cycle will help you be aware of others. I did not understand Mr. Wilson until Dennis annoyed me and classified me. Great leaders have tremendous self-awareness. As a result of knowing their own bias, they can feel the needs and biases of others. And this is the second priority for leaders: to understand the potential generational bias of their teammates and team members. Knowing the potential for one group to need more hierarchal styles and another to seek peers is at least a start at being a more effective leader.

The metamorphosis of family structures has changed the type of leadership and authority younger generation workers want. These changes place great stress on those who would attempt a single style of leadership.

Third, to succeed, leaders will need adaptable styles that change as they approach different individuals in the same workforce and workplace. In young tech environments, this may look easy, as often the generational bias, the leadership, the culture, transference, and work life cycle point are all aligned. But in more mature organizations, where we have workers from their late teens to their 80s, having multiple leadership styles is a challenge, but a must-have for the modern executive.

But fourth, and most importantly, we need to recognize that all stereotypes are simplistic. Whoever you seek to lead is an individual and unique. They have been shaped not just by their early formative years, but by previous leaders, cultures they have experienced, their personal challenges and experiences, and where they are in their life and work-life cycle.

Dennis and Mr. Wilson as companions, not adversaries

If anyone talked about any protected class the way the literature writes about generational stereotypes, Twitter would break from overuse and the public outcry would be deafening. Can you imagine us classifying races, genders, sexual orientations, religions, or ethnic origins the way we do folks of different ages? We consider it acceptable to categorize and classify age bands and generations and assign traits to them. This is because generation and age are really not a legally protected class, and moreover, we will all age so we feel some entitlement to self-deprecate. Sure, the Age Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967 prohibits certain employment practices with respect to those over 40, but it is not illegal to call a millennial lazy? How odd.

While there may be some merit to generational theory affecting how one starts in the workplace, workforce participants quickly become more unique as they interact with leaders and coworkers; as they participate in various corporate cultures and live and bring their personal lives and experiences into their workplace behaviors. Our generational bias based on the common cultural forces we experienced during our formative years are ground down over time. Workforce participants age themselves and experience a “work life cycle.” The work life cycle causes us all to progress through each generational stereotype. So we end up with some of each layer of the multigenerational cake in our guts.

Working well together in the workplace across the multiple generations is a lot like my experience over my lifetime, moving from a fun loving kid who did not understand Mr. Wilson, to becoming perceived to be Mr. Wilson. But what stories could I have told these children? What games from my childhood could I have taught them? I was not Mr. Wilson; I was a unique individual shaped by a variety of cultures and neighbors I had over the years. I was not Mr. Wilson, the stereotype of a grumpy old man. But I was because they thought I was, and the more they reinforced that stereotype I suppose the more I reflected it.

I think if I met Dennis and Mr. Wilson I could help them now. I would get them working on a yard project together. I would have Mr. Wilson teach Dennis how to do something. I would have Dennis teach Mr. Wilson how to smile. Commingling diversity brings understanding, and leaders can facilitate that. Because there was no leader to make me sit with the neighborhood children ringing my doorbell, not long after becoming Mr. Wilson I relocated to a downtown high-rise where I found all of the other Mr. and Mrs. Wilsons. Relocating to Wilson’s ’hood made me feel at home, but it did nothing to improve generational harmony and human progress.

As leaders in the workplace, we can do better. Your millennials are not Dennis, and you are not Mr. Wilson. While generational stereotypes are not completely irrelevant, if for no other reason than we think they exist, they can cause us not to work to understand and find the individual within. Great leadership and management are not about generations, they are about inspiring and igniting a human with latent potential to produce their best, and feel the fulfillment of doing so. Ensuring we clean our lenses and put in the effort to understand our talent as the individuals they are is the key to leadership success. Or maybe that is just the idealistic boomer inside of me, dreaming of a better world.