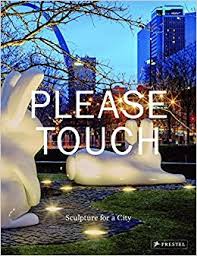

Opened on June 30, 2009, Citygarden is one of the chief accomplishments of the Gateway Foundation, a privately-funded nonprofit organization devoted to enhancing St. Louis’s public spaces. An open, urban garden filled with water and light, Citygarden showcases 24 works of sculpture across two city blocks of downtown St. Louis. Published by the Gateway Foundation, Please Touch: Sculpture for a City features a detailed map and photographic inventory of the space, as well as lush color photographs of some of Citygarden’s most memorable inhabitants, including Mark di Suvuro’s imposing red steel sculpture Aesop’s Fables (62-65) and Julian Opie’s playful video displays, Kiera and Julian Walking (102-103) and Bruce and Sarah Walking (66-67). One part Citygarden celebration, one part oral history, Please Touch is a handsome coffee table book, the kind that invites casual examination but typically poses no real intellectual challenges to its readers. Or so one might initially think. In the several short essays that accompany the book’s many photographs, however, Please Touch exceeds the constraints of the genre. The book’s contributors instead use Citygarden as a springboard from which to offer sometimes conflicting reflections about vexed concepts like public art and civic space.

Though the essays featured in Please Touch share no explicit subject other than Citygarden itself, the complicated task of naming and defining public art emerges as an unspoken thread that yokes together the book’s disparate voices.

Though the essays featured in Please Touch share no explicit subject other than Citygarden itself, the complicated task of naming and defining public art emerges as an unspoken thread that yokes together the book’s disparate voices. In “Why Public Art?” and “Thresholds: Public Art as Points of Entry,” contributors Robert Duffy and Patricia C. Phillips, respectively, grapple with these issues. Each writer prompts readers to consider whether or not it is possible–or even necessary–to define public art in order to discuss its place and function. A veteran arts and culture writer for local outlets like the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the now-shuttered St. Louis Beacon, Duffy places a higher premium on creating boundaries to demarcate what is and is not public art. In an effort to simplify a concept that does not yield easily to delimitation, Duffy even offers an equation (27):

A (work of art) + P (public) = PA (public art)

Of course, Duffy presents this mathematical formula partially in jest. He acknowledges that “just because an art-like object is plunked down in a place accessible to all, doesn’t mean it ‘public art’—or rather it is such only as a result of a mathematical summing up, or an accident of placement” (27). For Duffy, Citygarden is not merely a site populated with public art; rather, it is an “ensemble, a work of public art itself” (27).

In his essay, Duffy zooms out and takes readers on a curated micro-history of public art that begins in Ancient Mesopotamia and lands in the present with Citygarden. On the subject of ancient public art, however, Duffy remains vague. He does not tether his historical overview to any particular examples, though one could easily imagine the ziggurats of Mesopotamia or the pyramids of Giza as reference points. Nevertheless, he perceives a genealogical link between the unnamed prehistoric beginnings and contemporary iterations of public art. In both cases, the works in question are characterized by more than “mere accessibility and visibility” (28). And yet, what is the “more” to which Duffy alludes? What differentiates the accidental from the intentional, which Duffy also proclaims public art must be? While Duffy writes with sometimes maddening circumspection, it is power that lies at the heart of his answer. If the triumphal arches, columns, and monuments that comprise what Duffy sees as public art’s “old order” once operated as instruments of governmental and religious authority, then the new guard possesses a different relationship to power. Public art, Duffy writes, “now routinely and often acerbically speaks truth to [power], or avoids power altogether and reduces the observed world to fundamentals” (31). How this assessment speaks to Citygarden is not immediately clear. While Citygarden is a public space, it is not a manifestly political one. Perhaps, for Duffy, Citygarden exemplifies a new breed of public art not because it necessarily confronts power, but because it pares down the world to its most essential elements: water, light, earth, beauty, people. More than a chance gathering of modernist sculpture, Citygarden is an outdoor space with purpose(s). As an urban sculpture garden, Citygarden exhibits manifold appeals to a diverse range of visitors and, in the process, “serves a coalescing function” in a divided metropolis (27).

While Duffy writes from the perspective of a hybrid philosopher-historian, Patricia C. Phillips approaches public art and Citygarden, in specific, as a tourist-cum-anthropologist. Phillips’s contribution to Please Touch marks her first visit to Citygarden, which she approaches quite directly: on foot, from her nearby hotel. A former Dean of Graduate Studies at the Rhode Island School of Design, Phillips has published widely on the interrelations between contemporary public art, architecture, and the environment. In her writings, she frequently employs the concept of the “threshold” as a means of considering public art and its operations. Phillips understands thresholds as “portals and apertures that allow us to navigate through and arrive at animating ideas of common purpose through multiple perspectives” (35). In her conceptual framework, thresholds “represent transitions and beginnings” (35).

For Citygarden, more specifically, the Arch functions as an anchor, a visual reference point with which it is in constant conversation. If the Arch is an imposing monument that marks St. Louis as a city of transition and in transition, then Citygarden emerges as a space where metamorphosis is possible on the ground.

Though Phillips has written about public art in various places, the threshold metaphor is somehow doubly resonant for St. Louis, a city so preoccupied with gateways. And, this confluence of theory and place is not lost on Phillips. There is no conversation about the Gateway City without mention of its namesake landmark: the Gateway Arch. Arguably the most visible and monumental work of public art in St. Louis, Eero Saarinen’s modernist sonata in steel looms large over the city, both physically and psychologically. Like Duffy, Phillips recognizes that the Arch belongs to another, earlier generation of public art, one concerned with iconicity and the realization of a singular vision. Constructed between 1963 and 1965, the Arch rose at a particular moment in the city’s history. In Phillips’s appraisal, “Saarinen’s project represented undaunted aspiration, the promise (not the failures) of urbanism and modernism, and another way to ‘symbolize’ the realities of inner-city America in the mid-1960s” (36). Phillips’s characterization of Saarinen’s mid-20th-century architectural feat could easily apply to the St. Louis of today. Long held in competition with other Midwestern cities like Chicago and, more recently, a resurgent Detroit, St. Louis seems to be in a perpetual state of becoming. This is especially the case for downtown St. Louis, whose revitalization is more an endless condition than a finite enterprise.

For Citygarden, more specifically, the Arch functions as an anchor, a visual reference point with which it is in constant conversation. If the Arch is an imposing monument that marks St. Louis as a city of transition and in transition, then Citygarden emerges as a space where metamorphosis is possible on the ground. To first-time visitor Phillips:

Citygarden felt open, optimistic, and paradoxically intimate, as public space can be when people together are transported through embodied experience into ideas and imaginings. If we accept that thresholds—and gateways–are sites of transition, Citygarden is an active intermediating zone that welcomes different views, activities, forms of play, interventions, and levels of engagement (40).

The image of the threshold pops up again in the book’s concluding essay from Peter MacKeith, Dean of the Fay Jones School of Architecture at the University of Arkansas. In “St. Louis: The City Imagined, The City Experienced,” MacKeith poetically exhorts readers to engage their imaginations and to envision multiple facets of the city’s identity. St. Louis as a city of ample public lands and public parks. St. Louis as a city defined by waterways, like the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers. In his final dream-like imagining, MacKeith urges us to visualize “a condensed garden, centrally located and opened to all” (171). This garden represents an “ideal city: a city to be experienced in all its richness and diversity, to be appreciated in all its fragility and sensuousness, to be understood in all its history, challenges, and potentials. This garden suggests a city of equal rights, opportunity, and access, a city of contemplation and imagination” (171). For MacKeith, this garden is Citygarden.

This garden represents an “ideal city: a city to be experienced in all its richness and diversity, to be appreciated in all its fragility and sensuousness, to be understood in all its history, challenges, and potentials.”

Duffy, Phillips, and MacKeith equally conceive of Citygarden as a space pulsing with almost utopic energy. The contributors suggest that Citygarden not only offers sculpture for a city, but also, perhaps more importantly, sculpture of and about a city. The command of the book’s title, Please Touch, need not be taken so literally. Citygarden is itself a place of contact, drawing together local and out-of-town visitors with the city’s past, present, and aspirations for the future.