“Search out thy blindness,” Helen Keller’s poem invites us, “It holdeth riches past computing.”

Her words echoed in my memory when, closing my eyes to sleep one night this past year, a pro-cession of printed words moving across an expanse of red appeared, a red dark as claret. The words paraded past in what seemed slow time. They were a little too far away for me to decipher. Stand still, I thought. Wait for me to read you. I could almost make them out, but there was no way to draw them closer to do so. They were printed in the font I recognized as Courier New. Under shuttered eyes I saw them flow on, crossing a wine-dark river some blind people say is all the sightless see. They were English words, composed of the letters of the alphabet you and I learned by heart in the morning of our lives, chanting them as our fingers traced them on the pages of our first copybooks.

This strange vision returned a few weeks later, and after a time, returned again and yet again, vanishing when I blinked and opened my eyes. What does this signify, I puzzled, these rows of words flowing onward in a procession stately as a pavan, moving right to left across the inner field of vision? What is their text, and for whom is it or was it inscribed? When I opened my eyes and then closed them again, I saw unrelieved darkness. The words left as they had arrived, in an instant; I could not conjure the merest trace of what I had seen. By opening my eyes, I had broken a spell.

This happened again and then again as yesterdays passed into todays. After a time, there came a change in this baffling inner vision. The words remained motionless, and seemed to be printed on a red brick wall. I strove fiercely to bring them into better view. But squint as my closed eyes did at my bidding when I pressed them shut firmly, they remained indistinct. One night I asked myself aloud, What is this that is coming to me? Is this a sign of the bleak aftertime of the loss of eyesight that befalls the remaining life of a lifelong writer and lover of books?

The Lord giveth and the Lord taketh away. Blessed be the name of the Lord.

In my student days, I read of a proverb in the oral tradition of a preliterate people, a teaching that whomever or whatever you pass by in the morning of life you will pass by again in the evening.

A memory came: a philosopher—I think it was Ernst Cassirer—wrote of the delight children take in learning the names of things they ask about. He thought that each new word a child learns serves as a walking-stick the child uses on his or her way through an ever-expanding universe.

“Read, Grandma,” my toddler granddaughter implored whenever I looked up from reading to her and her brother and asked what they thought of what we were sharing, “Don’t talk, just read.” Those were the days of the Golden Age when I read aloud to little children, first as parent of their mother, my daughter, and of her brother, then in the Age of Restoration as grandparent of theirs. “Nothing gold can stay,” Robert Frost’s poem says. Yet there can be moments when the Past returns.

This June, the procession of English words paraded past my open eyes in the bright light of day, and I am beginning to read their message. I read in the New York Times (Motoko Rich, “Pediatrics Group to Recommend Reading Aloud to Children From Birth,” June 24, 2014, p. A14) that the American Academy of Pediatrics would announce that Tuesday that doctors will tell parents to read aloud to their children from infancy on. This is the first time the Academy, which advises parents to keep children away from screens until at least age two, has issued a policy on early-literacy educa-tion. Reading, talking and singing to children are important in increasing the number of words children hear in the earliest years of their lives. While some affluent, highly educated parents read poetry and play classical music to their children even when they are in utero, research shows that many parents do not read to their children as often as educators and researchers think is crucial to developing pre-literacy skills that help them succeed once they attend school. A federal survey of children’s health found that 60 percent of American children from families with incomes at least $95,400 are read to daily from birth to age 5, compared with about one-third of those from families living below the poverty line of $23,850 for a family of four. “With parents of all income levels increasing-ly handing smartphones and tablets to babies, who learn how to swipe before they can turn a page, reading aloud may be fading into the background.” What is more, pediatrician Alanna Levine observes, parents today must compete for their children’s attention with portable digital media.

It was not long after learning to trace letters of the alphabet that I practiced drawing them freehand as budding artists do, and then in cursive writing connected letters into words I harvested from reading and listening to what was spoken in the life around me.

My parents never read aloud to me or my four siblings. Yet my older sister and I became avid readers from an early age, and often had to be called repeatedly to close our books and attend to our chores. Our mother, whose schooling ended with the eighth grade, read books and papers to the end of her long life; her penmanship, very like gothic font, was one of the most exquisite I have ever seen. Our father’s schooling ended after one year of high school. Yet he was self-taught in the math and related skills required to become a licensed master plumber in midlife; and among my cherished memories of childhood were the times he walked beside me to the local branch of the Chicago Public Library. He told me that one of my first words was book, which he overheard me murmuring in my sleep.

To this day, I remember with an inexpressible joy the thrill of first learning to read—the feeling of empowering myself to open books in solitude, and to enter the worlds inside them—to spirit myself to live imaginatively there. Way leads to way, Robert Frost says in his poem. For one born with what the ancients called “the itch to write,” by the age of 7 or 8 I knew that reading and writing are entwined. It was not long after learning to trace letters of the alphabet that I practiced drawing them freehand as budding artists do, and then in cursive writing connected letters into words I harvested from reading and listening to what was spoken in the life around me. Soon I was filling pages with words telling of my thoughts and imaginings, then signing them with my name.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream tells of the writer’s way: “And as imagination bodies forth/The forms of things unknown, the poet’s pen/Turns them to shapes, and gives to airy nothing/A local habitation and a name.”

The first light of creativity in writing as well as drawing dawns with the child’s impulse to make a double of what has been shown—a semblance of the form as best as one’s own hand can bring forth: a squiggle one’s very own on the paper. “Have you got that pencil with you?” my mother said she overheard me at age two demand of my older sister. In our family, it was forbidden to give pencils to toddlers. But in the fullness of time I came of school age and into our birthright. Hence-forth I could inscribe the wonders of the world within and bring them into this one by my hand; I could people them, giving words to the stories their lives told as they emerged from “airy nothing.”

Cursive writing is the fertile crescent of creativity in literature and the fine arts. In writing by one’s own hand, we learn how to build our very own bridge between the life of the world within and the world out there. Researchers today find evidence that “the links between writing by hand and broader educational development run deep, and that children not only learn to read more quickly when they first learn to write by hand,” but also “remain better able to generate ideas and retain information” as well. (Source: “What’s Lost as Handwriting Fades,” by Maria Konnikova. The New York Times, June 2, 2014) In a 2012 study, children who had not yet learned how to read and write were given a letter or shape on an index card. They were asked to choose between any one of three ways to reproduce it: trace the image on a page with a dotted outline, draw it on a blank sheet of paper, or type it on a computer. After doing so, they were placed in a brain scanner and shown the image again. The finding pointed to the importance of the initial process of duplication. Children who drew a letter freehand exhibited increased activity in three areas of the brain that also are activated by adults when we read and write (the left fusiform gyrus, the inferior frontal gyrus and the posterior parietal cortex.) For children who traced or typed the letter or shape, the activation of these areas was significantly weaker. Dr. Karin James, a psychologist at Indiana University, noted that the task first to plan and then to execute our action by making our own facsimile of an image freehand on blank paper is not required if we are given a traceable outline and asked to make its double by tracing it or by pressing the key with the symbol for it on a keyboard. She says this study “is one of the first demonstrations of the brain being changed because of the practice “of reproducing an image by drawing it on paper.”

Another study that compared children who physically form letters with children who just watch others doing this, suggests that it is only the actual effort that engages the motor pathways of the brain and delivers the benefits for letter recognition of learning by handwriting. And still another study involving children in grades two to five demonstrated that printing, cursive writing and typing on a keyboard each is associated with distinct and separate brain patterns, and each results in a distinctive end product. Children who composed text by hand produced more words more quickly than doing so on a keyboard, and expressed more ideas. Also, brain imaging showed that of those in the oldest group asked to come up with ideas for a composition, the ones with better handwriting showed greater neural activation in areas associated with working memory, and increased overall activation in the networks of reading and writing.

It appears that the benefits of writing by hand live on after childhood’s end. Though many adults prefer typing to writing longhand for speed and efficiency, the price may be a diminishing of our ability to process new information. It has been found that students learn better when they take notes by hand than when they type on a keyboard. Writing by longhand permits one to process the contents of a lecture and reframe it; the process of reflection and manipulation can lead to a better grasp of the material encoding of memory.

… brain imaging showed that of those in the oldest group asked to come up with ideas for a composition, the ones with better handwriting showed greater neural activation in areas associated with working memory, and increased overall activation in the networks of reading and writing.

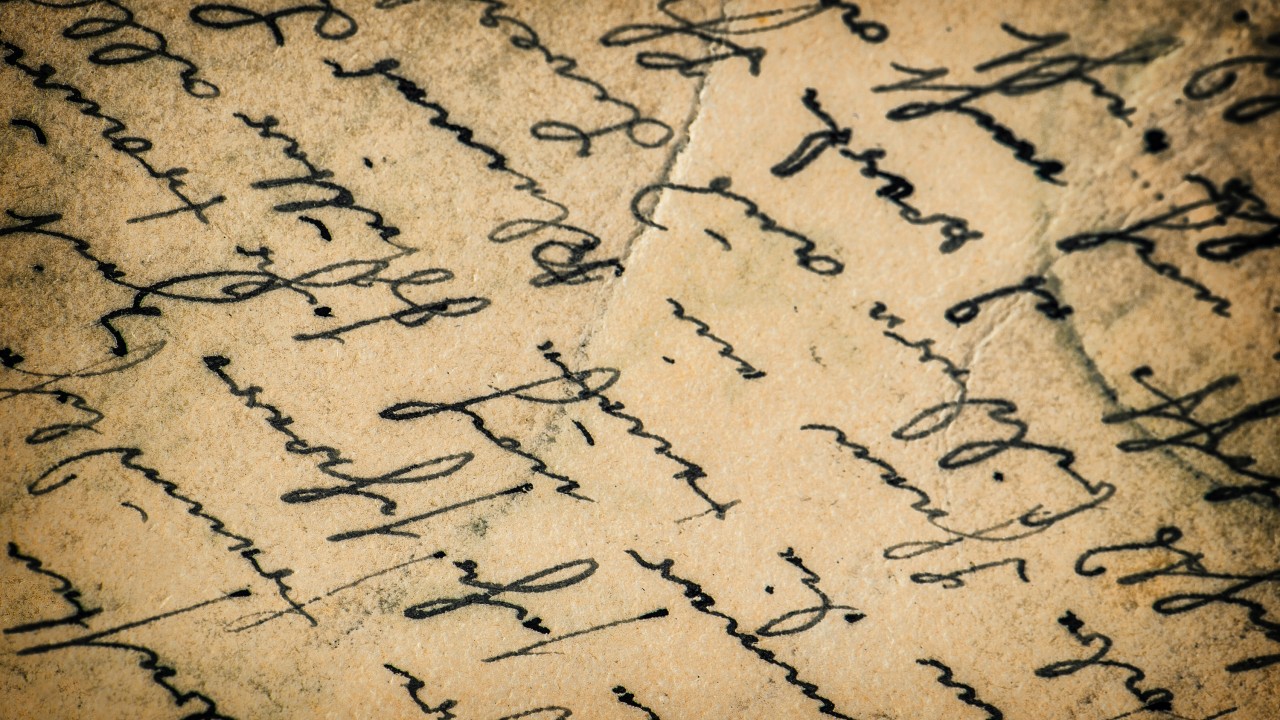

Fellow writers, this is a call to do what we can to save cursive writing. The Common Core standards, now adopted by most states, call for teaching writing that is legible, but only in kindergarten and first grade. Thereafter, the emphasis shifts to proficiency on the keyboard. Of the losses to future generations threatened in our lifetime, the disappearance of cursive writing is among the most grievous for me to contemplate, for it is here where we first discover our creativity. A letter in the June 9 New York Times from Patricia Siegel responding to this article reminds us that “Hand-writing is our personal stamp, … and should be allowed to develop and flourish in children … the way we draw and write goes to the heart of who we are.” Another, from Valerie Hotchkiss, Director of the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois, warns that “as knowledge of cursive fades, so too will our ability to do historical research.” Hotchkiss says her Library has more than “three miles of literary archives containing letters and manuscripts by Mark Twain, Carl Sandburg, Marcel Proust, Gwendolyn Brooks and H. G. Wells, among other luminaries.” She asks how “new generations of non-cursive readers” can “make heads or tails of these documents—let alone their own parents’ love letters” and reminds us that “by not teaching cursive, we are excluding those who come after us “from the ability to do primary research or interact with the past.”

Search out thy blindness / It holdeth riches past computing Words from the heart, heart-thoughts rise up, and lights heretofore hidden shine forth; a current is activated and flows between them and their realization by the writer’s hand. These are our voiceprints, prints of our singular, signature voice. It is in meditation, in reverie, in dreams, that we may dive down to our most profound joys and griefs. As we move ever more deeply into what is within, we may make discoveries about ourselves—even in late life when they reveal themselves through the wavering hand of great age—that transform us. Yesterday morning, for the first time in the bright light of day my writing hand became transparent and I could see through it the procession of words parading past. I still could not bring them nearer to read them as I read print on the page. But their return and my search thus far have shown me the way to acknowledge here my fear of loss and speak its name, and to declare what I have loved and passionately long to preserve for our inheritors in the after time.