The title “executive producer” followed by “Norman Lear” capped the credits for five of the most popular sitcoms of the 1970s—All in the Family (1971-1979), Maude (1972-1978), Good Times (1974-1979), The Jeffersons (1975-1985), and Sanford and Son (1972-1977)—but the words were nearly superfluous. The main characters had only to open their mouths for viewers to know who had created them, and what told on them was that, well, they told everything: their beliefs, their (many) prejudices, seemingly their every thought, no matter whom it might offend. Those thoughts had had ample time to ripen in the minds of these characters, who were typically in their mid- to late forties when their series began (Fred Sanford, Redd Foxx’s character on Sanford and Son, was a good bit older than that); these were adults, with grown children who rebelled against their parents or simply held up under their bluster as best they could.

During the original runs of these programs, I was a child, living in a household where there was a TV on if anybody was awake. I followed the antics of Fred Sanford, Maude Findlay, George Jefferson, All in the Family’s Archie Bunker, and the Evans family of Good Times the way I followed the comings and goings of my own family members. Sometimes there were even similarities: Michael, the youngest Evans child, was roughly my age—and skin color—and his dad died not long after mine did. As that last detail suggests, for all their uproariously funny moments, some real sh-t happened on those shows. Archie once cheated on his wife, Edith; Edith narrowly escaped being raped in her own home; the ardent feminist Maude agonized over her late-in-life pregnancy before having an abortion; and, in perhaps his finest moment, the unapologetically racist Archie shunned neighbors who tried to recruit him for the local KKK. I got to know the details of these characters’ lives, to know what frustrated them, how sweet they could be one moment and how maddening the next. What I didn’t know about these TV characters—because they were among the first I ever followed—was that TV had never seen anything like them before: the issues they faced, the subjects they discussed, and the attitudes they expressed, which made them no more than representative Americans, were without precedent in the history of broadcast entertainment. Television prior to the arrival of Norman Lear’s family of characters was roughly equivalent to painting before Brunelleschi and the use of perspective, limited by a flatness that is especially obvious in retrospect.

I use the word “family” advisedly, since Lear’s characters—like those in that other mainstay of my growing-up years, Marvel Comics—all inhabited the same universe. Maude was Edith’s cousin; Florida, the mother on Good Times, began life as Maude’s housekeeper; the cleaning-store owner George Jefferson was Archie and Edith’s neighbor in Queens before he and his wife, Louise (“Weezie”), moved on up to the East Side, to a dee-luxe apartment in the sky-hy-hy. (Fred Sanford and his son, Lamont, didn’t know any of the others, no doubt only because they lived on the opposite coast.) And these characters’ mix of the lovable and the exasperating made them like members of our families.

Television prior to the arrival of Norman Lear’s family of characters was roughly equivalent to painting before Brunelleschi and the use of perspective, limited by a flatness that is especially obvious in retrospect.

The cantankerous junk dealer Fred Sanford’s love for the thirtyish Lamont (Demond Wilson) did not keep him from calling his son “Dummy” as if it were his name. Fred, who had had even longer than Archie to stew in his own prejudices, disliked and distrusted whites but—as sometimes surfaced—didn’t necessarily think very highly of his fellow blacks, either. In one episode (TV’s earliest investigation of intra-racial prejudice?), Fred needs a dentist and informs Lamont that he wants a white one. Naturally, when the two arrive at the dentist’s office, Fred is seen by a middle-aged black man. Fred questions the man about his credentials, finally leading the dentist, who knows the score, to leave and send in his young white colleague. Fred is relieved until he asks more questions and finds that this fellow was trained at a third-tier institution. If you like, the dentist cheerily tells Fred, the boss can work on you. Fred eagerly agrees, the young man exits, and—to laughter and applause from the live studio audience—the first dentist returns. Turn the dial (back when you could do that), and there was George Jefferson (Sherman Hemsley), the little rooster whose constant crowing could make you forget that he had something to crow about, the black self-made man whose verbiage sometimes, and sometimes accidentally, contained hard-won wisdom. One episode has George being blackmailed by a childhood friend (played by the underappreciated Moses Gunn, who also turned up as the love interest of the widowed Florida on Good Times, and who was featured in such iconic black film fare of the 1970s as the first two Shaft movies and Roots). Pay up, the friend says, or I will tell your wife about the things we used to do as poor young street punks. George decides to tell Weezie (Isabel Sanford) himself, only to discover that she learned about it all long ago from George’s mother. George then speaks the line that sums up the human condition: “You mean all this time I was worried about that, when I coulda been worrying about something else?!” And then there’s Maude (Bea Arthur), whose outspoken liberalism could blind her to her own racism, as when she tells a black acquaintance who expresses fondness for a white singer that she should support performers of her own race. But one of the most heartbreaking moments in any of Lear’s shows finds Maude complaining to a therapist about her father, then suddenly remembering an act of kindness and self-sacrifice on his part—and weeping over having failed to appreciate him. The Evans family on Good Times lived in a dangerous Chicago high-rise housing project; the eldest child, J.J. (Jimmie Walker), may have struck some as a black stereotype, but if my own neighborhood was at all representative, that did not stop working-poor black families from tuning in as if they themselves were on TV, which, in a sense, they were, for the first time.

But for sheer force of personality, and impact on the medium of television, none of Lear’s creations stood taller than Archie Bunker, brought to life by Carroll O’Connor. Archie became known as TV’s first bigot (or, in some circles, as “our kind of guy”), but he was merely the first to have his bigotry revealed. (Would I have been welcome at dinner in the Cleaver household of Leave It to Beaver, broadcast 1957-1963? I have my doubts.) His bigotry and sexism were just parts of the whole, and if the mark of a round character is that we cannot maintain a single attitude toward him or her for very long, then Archie was as round as they come. He had a deep love for the sweet, dim-witted wife (the wonderful Jean Stapleton) he was forever telling to “stifle”; he had an affection and respect, which he would have died to avoid admitting, for the liberal son-in-law (Rob Reiner) with whom he was continually butting heads and whom he allowed to live rent-free in his home; he shouted his contempt for whole groups of people whom he would not have had it in him to harm; he was uneducated, limited, and in real danger of being left behind economically and socially, and his being smart enough to know all this was the source of his rages against contemporary life, which could arouse in us a mix of anger and sympathy usually reserved for kin.

If Archie seemed to have been pulled from life itself, to have been a real person, that is largely because he was based on one: Herman “H. K.” Lear, Norman’s dad.

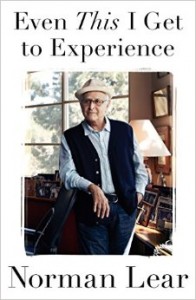

Does a man ever get over his father? Born into a Jewish family in New Haven in the summer of 1922, the second child and only boy, Lear developed toward H.K. a reverence that withstood a great deal before souring, which it never did completely. Like Archie, H.K. was a large personality whose faults were proportional to the rest of him. (He would even tell his wife, Jeanette, “Stifle!”) “He was a flamboyant figure with what appeared to me to be an unrivaled zest for life, and he seemed to fill every room he was in,” Lear writes in his warm, frank, very enjoyable autobiography, Even This I Get to Experience. “He leaned into everything that came his way. He bit hard into all of life, and everything in the same measure.” He adds a few pages later, “My father was extremely outgoing and affectionate, but the underside of his great good nature was not admirable. Enormously insensitive, he treated absolutely everybody the same way, never taking into consideration that the person he was talking to now might be just a little different from the person he was talking to ten minutes before.” Unlike Archie, H.K. was a con man: he was arrested in 1931 for selling fake bonds to a brokerage house and spent three years in prison. For a time, without its breadwinner, the Lear family broke up; Norman lived with an uncle and then his grandparents in New Haven between the ages of 9 and 12, while his mother and sister resided in Hartford. (If Archie was Norman’s father, then perhaps Edith was the mother Norman wished he had had. When Norman complained later to his mother that they had barely seen each other during the years they lived apart, the response from Jeanette Lear—“a world-class narcissist”—was, “Oh, please!” When, at age 61, Norman told his mother that he was to be one of the first inductees into the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Hall of Fame, she said, “Listen, if that’s what they want to do, who am I to say?”) Lear writes of living with his uncle, aunt, and cousins during his parentless years, “My way of singing for my supper … was to make them laugh a lot. I thought it was my obligation to entertain my cousins because I was the beneficiary of their family’s largesse, so I would tell them stories, especially stories taken from films, and I did impressions of the actors.” If there is a more revealing statement about the true roots of comedy, I have never heard it.

Like many a man before and after him, Norman Lear seems to have spent a lot of time running both toward and away from his father’s example. Even This I Get to Experience details a long life in which Norman Lear has largely emulated H.K.’s zest for adventure, though a good bit more successfully and with a tad more sensitivity than his dad (even if, once in a great while, he has displayed similar bone-headedness, evident in or two ill-advised business moves). After H.K.’s release, the family reunited and lived for a time in Brooklyn before returning to Connecticut and settling in Hartford. Norman Lear wrote and acted in theatrical productions during high school and spent two happy years at Boston’s Emerson College—during which, as a Jew, he nonetheless “never lost the sense of being outside looking in”—before enlisting to fight in World War II. He saw action as a crew member in a B-17 bomber, flying 52 missions in Europe; during one such mission his best friend was killed. After the war Lear had a brief stint as a press agent, worked somewhat longer for the shaky company founded by his father, and then relocated to California with his young family to try to revive his career in publicity. (“Hollywood’s not for you, dear,” his mother told him.) Instead, through ingenuity, chutzpah, and rather amazingly good luck—a combination that would come through for him on quite a few occasions—he and his cousin’s husband wrote a comedy routine for Danny Thomas, who went on to perform it for years. Lear’s foot was in the door of the entertainment world, and soon the rest of him would burst in. Over the next two decades he worked as a writer and/or producer on shows starring Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis, Martha Raye, Tennessee Ernie Ford, George Gobel, and Andy Williams, among many other TV and film projects, and founded Tandem Productions (in 1958) with Bud Yorkin. Through Tandem, Lear created the programs that would dominate the ratings and make him truly famous, beginning with All in the Family. Nearing his fiftieth birthday at that point, having seen a good bit of life himself, he could inform the experiences of his middle-aged characters.

“My way of singing for my supper … was to make them laugh a lot. I thought it was my obligation to entertain my cousins because I was the beneficiary of their family’s largesse, so I would tell them stories, especially stories taken from films, and I did impressions of the actors.” If there is a more revealing statement about the true roots of comedy, I have never heard it.

Perhaps of necessity, the sections about Lear’s signature creations (which also include Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman, broadcast 1976-1977) are the most interesting in the book. Among other stories, he discusses his fights to get various lines of dialogue past CBS executives and on the air, talks about the difficulty of working with Carroll O’Connor, and reveals his struggles with John Amos and Esther Rolle, who, playing the parents on Good Times, were so worried about the images of the black family they were projecting that they had to be cajoled into making what would be some of the series’ best episodes. (Lear does give short shrift to Fred Sanford, who for my money was as original a TV creation as Archie Bunker and who was less groundbreaking mainly because Archie came first.) All that said, Lear’s refreshingly self-deprecating book is fascinating as a whole, exploring the many facets of a very full life, including his three marriages and numerous children; his extensive liberal activism (he established People for the American Way, for example); and, through it all, his largeness of spirit, which transcended its darker sources and gave birth to some of the most memorable characters of our time.