The latest Supreme Court decision involving the rights of same-sex couples, Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, issued on June 4, upheld the rights of a Colorado baker to refuse to make a cake in celebration of a same-sex wedding. The Court based its 7-2 decision on the belief that the Colorado Civil Rights Commission’s denial of the baker’s rights was based on “a clear and impermissible hostility toward the sincere religious beliefs that motivated his objection,” as Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote for the majority. It seems that if the Colorado Commission did not evince “hostility,” then their decision against the baker could have been more convincing.

But the emotions at play include more than the “hostility” toward religious-based discrimination. Feelings also attend to the expression of religious principles themselves. This interplay of emotion is fundamental to the impasses between religious liberty and anti-discrimination law. To better hone our sense of the emotional stakes here, we have to look again at how the massively successful marriage equality movement defeated its religious opponents in emotional terms. They are rooted at the local, interpersonal level.

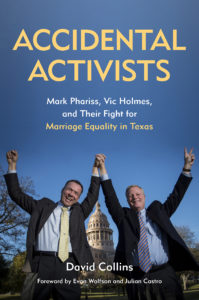

As told by David Collins in Accidental Activists: Mark Phariss, Vic Holmes, and Their Fight for Marriage Equality in Texas, the legal battle for marriage quality in Texas was a melodrama. Bad guys, trying to prevent the marriage plot, scurry in the background as Collins alights more heavily on the ‘good’ to be found in communities and relationships. His goal is the propagation of the faith in the committed romantic relationship between Mark Phariss and Vic Holmes, two of the lead plaintiffs in the 2013 Texas marriage-equality case DeLeon v. Perry. Collins takes us along as they race to file, appear before the court, wait for decisions, meet with attorneys, and try to escape from under the burgeoning legal apparatus on weekend getaways, where they continue to respond to Facebook messages to keep the faith alive. Phariss and Holmes withstand legal roadblocks put up by the state and the particularly rancid climate of discrimination and marginalization of same-sex attracted people in Texas. The case reaches the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, and during its deliberation the Supreme Court of the United States rules in Obergefell v. Hodges on June 26, 2015 that every state in the country must give full legal recognition to same-sex couples seeking marriage. At the end of the book, we join Collins at Phariss and Holmes’ lavish wedding and leave with a sense that the purpose and celebration of marriage, and all the people involved in the fight for it are right, true, and wholesome.

This interplay of emotion is fundamental to the impasses between religious liberty and anti-discrimination law. To better hone our sense of the emotional stakes here, we have to look again at how the massively successful marriage equality movement defeated its religious opponents in emotional terms. They are rooted at the local, interpersonal level.

Everything about the marriage-equality movement had been managed and manicured for years before the major LGBT legal organizations and funds decided to make their case through the courts. Many queer people critiqued the movement for spending an enormous amount of time and resources to gain entry into a socially discriminatory institution. Their critique aimed to redirect the fight for access to the rights and benefits of marriage in ways that did not require one to get married. That approach was, and still is, bound up with a dismissal of marriage in its entirety as straight, patriarchal, and consumer-driven, a position which has never had nearly as wide of an appeal as marriage equality.

Collins’ story of marriage equality in Texas is straightforward. He provides an uplifting narrative about how a same-sex romantic partnership is validated by the government and comes to hold a more respectful and comfortable place among friends, family, and the larger community. Setbacks are setbacks. Wins are wins. Hopes and fears are clear. This emotional transparency makes the storytelling rather simplistic. But it evinces a reality the queer critique of marriage has failed to consider: Many people establish their personal moral compass in the melodramatic mode.

As literary and film scholars have shown, the very transparency of an emotional narrative—as it twists and turns around professions of love and dignity, victimization and salvation—is the key to its persuasive power in the realm of popular culture and law. The melodramatic mode was key to the success of the marriage-equality movement.

Melodrama has been commonly associated with qualities such as inauthentic and shallow. These understandings completely miss how people turn to melodrama’s clear-cut manifestations of ‘good’ and ‘evil’ in order to situate themselves on moral ground. As literary and film scholars have shown, the very transparency of an emotional narrative—as it twists and turns around professions of love and dignity, victimization and salvation—is the key to its persuasive power in the realm of popular culture and law.[1] The melodramatic mode was key to the success of the marriage-equality movement.

The heroes of a melodrama, which in the story of marriage equality are the plaintiffs, need to be palatable to a general swath of American society, and the jobs they hold worthy of the broadest respect. Mark Phariss is a corporate lawyer (now running for a Texas Senate seat) and Vic Holmes is a veteran of the Air Force. Of the other two plaintiffs on the case, Cleopatra DeLeon had also served in the Air Force and Nicole Dimetman was an attorney. They were, like the plaintiffs for marriage-equality cases across the country, handpicked by legal strategists. Frank Stenger-Castro, deputy general counsel in the San Antonio office of Akin Gump, the firm that represented their case, said that the description of Pharris’s and Holme’s lives “‘reads … like a telenovela!’” (89). Collins tells us how the reader should see the characters. “Like most Americans, averse to risk and conflict,” he writes, “Mark and Vic wanted only to live their lives quietly and enjoy the love they had found” (49). And so, the story goes, it was only accidental that they became activists. In reality, their activism was not at all accidental. Phariss began serving on the Board of Governors for the HRC, a major LGBT rights group, in 1997. Phariss and Holmes were simply both playing the role of ‘accidental activist.’ These men, as well as DeLeon and Dimetman, are more than worthy of our commendation for their stand-in work as upstanding couples. At the same time, the plaintiffs in marriage-equality cases across the country could have been switched out of one case and put into another, and the story would be the same.

The setting of their drama crucially evokes an American Dreamscape. Collins offers a kind of Architectural Digest tour of most of the upscale properties that feature in the story, including Phariss and Holmes’s houses. I cringed at his descriptions of them, and of the wedding itself, with their implicit praise of kitschy class. They read like a style magazine feature. Still, in representation and reality, high-end home furnishings and keepsakes from safaris are designed to signal comfort and enjoyment of all that life has to offer.

The words and phrases Phariss and Holmes used in talking about their case to the public and press, and by extension, the clichés Collins uses in telling their story, were based on “poll-tested language known to move hearts and minds” (100). The most prominent and important example of branding was the use of the phrase “marriage equality” instead of “gay marriage.” The goal was to encourage empathy through shared values rather than remind people of how their relationships might differ from each other.

Collins depicts Pharris and Holmes enjoying their lives together, and the encouragements and greetings they receive from others, in photographic snapshots, framed and placed around their cozy, welcoming home. He tells us of the personal struggles that led to moments of peace and warmth with friends and family, but he seldom shows with any nuance how those struggles played out. One of the few examples, perhaps because it directly relates to the marriage plot, is when Phariss and Holmes are split apart just as they are about to enter the Supreme Court to hear oral arguments in Obergefell. Their number in line has ensured them entry. The guard distributes the tickets only to give his last one to Holmes, with none left for Phariss. A representative of Faith in Action, an organization that opposes same-sex marriage, had slipped in line in front of them! Friendly eyes in the queue watched it all go down. One of the observers confronts the line jumper who, after playing innocent, gives up his stolen ticket. We identify with Phariss and Holmes in how they were cheated and lied to, and in their urge to reunite inside the courthouse, each one alternately giving their one ticket to the other until the drama is resolved, and all before the backdrop of the highest court in the land. The melodrama of the actual moment, as much as its retelling, is in the stark back-and-forth pull, the clear bullying of someone who did nothing ‘wrong,’ and the intense attachment between Phariss and Holmes that, when felt by observers and now readers, wins the day.

All of the snags and triumphs in Accidental Activists serve to reinforce a story much broader than marriage equality. It is the story of ‘good’ vs. ’evil,’ and it unfolds on every scale. The message is that there is right and wrong no matter where you live. Individual Facebook feeds, now a primary conduit of popular culture, are full of stories from around the world. Their number of likes and dislikes help orient people’s moral compasses. When Collins quotes from Phariss’s and Holme’s Facebook posts, he adds, “everyone knew what they meant” (112). That reassurance is what gives the melodramatic mode its social power to change hearts and even laws.

Collins does a nice job showing the melodramatic mode at work most powerfully in the arguments made in court. He has taken transcripts and recordings and created little dramas that read like the play Inherit the Wind adapted for the Lifetime Channel. All we are asking for is basic rights, the lawyers expound again and again.

The rhetoric around the story of this couple, like every other couple fighting for the right to be married, was at the core of the legal arguments used for all the marriage equality cases across the country, including the winning Supreme Court case. Collins does a nice job showing the melodramatic mode at work most powerfully in the arguments made in court. He has taken transcripts and recordings and created little dramas that read like the play Inherit the Wind adapted for the Lifetime Channel. All we are asking for is basic rights, the lawyers expound again and again. These rights should be given to these couples, they continue, because they are people who love each other with dignity. What Collins makes clear, perhaps inadvertently, is that the success of the legal arguments hinged on these melodramatic moments. Moral and emotional transparency is what made the plaintiffs, in the eyes of a majority of the judges, full “persons,” and, as such, they should no longer be victimized but treated with dignity under the law. The many judges who have decided on the question of same-sex marriage over the past decade certainly had to root their decision in a question of law: Are rights and protections being unlawfully denied certain people? Yet, the need for protections and rights, as well as its articulation and argument, relied entirely on the court seeing the plaintiffs as “persons” just as much as anyone else who already had the right to marry. The majority opinion of Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy in Obergefell rested on the belief that what makes same-sex attracted people “persons” deserving full protection under the law is how they uphold, in their choice to marry, “the highest ideals of love, fidelity, devotion, sacrifice, and family”—all the ‘good’ stuff (263).

• • •

What is implied but elided in this expression of melodramatic personhood is the sexual desire that brought the plaintiffs together in the first place. You may think that the sexual desire between them is not only private but has no bearing on their equal protection under the law. But it does. This is vitally clear in the words the lawyers used to argue for the sanctity of their relationships. These include “monogamy” and “committed,” which admit to the sexual desire at the core of their relationships while also cordoning off the need to know anything more about their sexual behavior.

The winning argument for marriage equality was designed to deflect any emotions, such as disgust or even horror, that individuals may have felt toward the sexual behavior between people of the same sex. These feelings of revulsion have been the go-to basis for the disqualification of the dignity of same-sex attracted people. Appeals to both legal reasoning and religious beliefs to discriminate have long rested on this emotional logic. Such was again the case when the owner of Masterpiece Cakeshop in Colorado declined to make a cake for a same-sex wedding celebration and argued for his right to do so.

The law and its subjects are now severely caught within this particular emotional logic in response to the sexual behavior between people of the same sex, mostly men. Its history can begin to untangle it. How the ‘sodomite’ became the ‘homosexual’ and then became the ‘gay person’ is one long story of how sexual behavior came to be the person who engages in it, which is the very basis of sexual identity itself. This is why it was also a necessity that homosexual sex, or ‘sodomy’ in its catch-all meaning, no longer be a criminal offense before marriage between same-sex couples could be granted a federal right. And it was not until 2003 that the Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas found sodomy laws discriminatory and illegal! That decision has not diminished the specter of sex. Phariss and Holmes had to “check out as ‘squeaky clean,’” in the words of their attorney Frank Stenger-Castro (64). ‘Squeaky clean’ means no criminal record or moral taint. For gay people, whose criminality was tied to their ‘disgusting’ sexual behavior, the primary markers of squeaky clean are monogamous and committed, which mean their sexual behavior is consensual, invisible, and benign.

The law and its subjects are now severely caught within this particular emotional logic in response to the sexual behavior between people of the same sex, mostly men. Its history can begin to untangle it.

When someone does see something ‘wrong’ with same-sex attraction, their mind goes right back into the gutter to find out what it is. Everyone knows that the baker at Masterpiece Cakeshop in Colorado was imagining what the two guys requesting the cake were ‘doing with each other.’ But what exactly did he conclude, and what was it based on? The customers, there with the mother of one of the grooms, looked like good, decent people, apparently. Regardless, the only difference between them and a heterosexual couple is that, theoretically, children can result from sexual intercourse between the latter. (In reality, heterosexual couples have fertility problems or do not want children and use contraception to prevent having them.) The crucial point is that same-sex marriage and the sexual identity of same-sex attracted people are different from heterosexuals and their coupling if compared on these terms. This was the main legal argument used against marriage equality: Since same-sex couples cannot produce children, the state has no interest in supporting those couples. Indeed, it has a more active interest in preventing their marriages because those couples do not harbor, solely between themselves, the potential for human reproduction. Treating their relationships the same as heterosexual marriages that theoretically could result in children weakens the larger social structures that support reproduction. This teleological reasoning is important precisely in how its terms gain powerful traction through the melodramatic mode. Now it is the gay couple, undermining the social order, that is ‘evil.’

The court ultimately decided that denying same-sex couples the right to marry will not affect children or childbearing in any nefarious way. To disqualify same-sex couples along those lines is discrimination. Anti-discrimination law says, ‘treat me without recourse to what you might think my sexual identity means; treat me as a full person.’ The paradox is that these laws are premised on the same logic of identity that reduces people to types, with all the moralizing language that comes in their wake. The way around that paradox has been to cordon off the question of sex—one of the most emotionally instigative questions—by presenting same-sex couples, and their marriage celebrations, as squeaky clean as possible.

• • •

This image of the squeaky-clean couple, set before the court of public and legal opinion, continues to incite a queer critique of marriage as a commodified and restrictive institution. In the January 2017 cover story of Harper’s Magazine, titled “The Future of Queer: How Gay Marriage Damaged Queer Culture,” author Fenton Johnson takes as his target “the predominance and glorification of Fortress Marriage as the norm: the married couple whose friends are all couples, who divide the world into inside and outside, who practice an intense, couple-centered version of collective narcissism.” While Johnson gestures toward the fact that marriage limits access to many legal rights to married couples (although he does not mention how legal theorists and practitioners continue to work to delink that access from marriage), his focus is elsewhere. For him, “Our salvation, our literal salvation in the here and now, in this nation, on this planet, requires our abandoning those ancient clan divisions in favor of the understanding that we are all one.”

How the “collective narcissism” of marriage differs from being, in Fenton’s world, “all one” is truly puzzling. It is important to dwell on this assertion for how it, and his “manifesto” as a whole, also operates in the melodramatic mode. Much more than Collins, Fenton’s melodrama rests on the dispersion of his enemies. They include the patriarchal straight culture that has upheld Fortress Marriage, as well as people like Phariss and Holmes who are apparently strengthening its walls in their work for marriage equality. One of the more prominent and early gay enemies in that line of work was journalist Andrew Sullivan. In a January post for New York Magazine, Sullivan, while reiterating the importance of the marriage-equality movement for “average citizens seeking merely the same rights and responsibilities as everyone else,” called out the radical left, implying the queer critique of the marriage movement and marriage itself, as reopening a public divide around the question of marriage and threatening the progress he sees in marriage equality. Sullivan cites a recent study from GLAAD (Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) showing that discomfort around LGBT people, and reports of discrimination, have actually gone up for the first time since the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision in favor of marriage equality. GLAAD suggests that the increase is a result of the extreme rhetoric of the right, and the particularly regressive conservatism circulating around President Trump, to which Sullivan also nods as a contributing factor.

Both sides of the gay argument here are limited, but it has to do with their emotionally descriptive language rather than their particular political positions. While the melodrama of marriage has won the right for same-sex couples to get married, we need another rhetorical genre to better understand and reveal what the cake maker and others are trying to wrap their heads around in the face of same-sex coupling. Again, it has everything to do with the sexual bond. The melodramatic mode affords a feeling of oneness between people precisely by passing over how the sexualization of their bond introduces an instability at its core. What is the sexual but the byproduct of the precarity of knowing, while always trying to know and imagining knowing, what holds people together as ‘one’? As Justice Kennedy wrote in his opinion in Lawrence v. Texas (the case that found sodomy laws discriminatory and illegal), these “intimate and personal choices … are central to … liberty …. At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of … the mystery of human life.” The recognition that same-sex couples pursue that mystery with as much dignity as any other couple, without any observer ever really knowing what goes on between any two people, is what won the case for marriage equality. What is urgently needed now is a clarification of the emotional logic of the sexual that will begin to reveal exactly how the mystery of human life triggers such responses as a baker’s over-sexualized assurance of what two people are ‘doing with each other.’ ‘Good’ and ‘evil’ are a way around the question.

No mere celebration of love, marriage is a public witnessing to the precarity of the sexual bond and the nexus of trust that holds it together. Every side of the debate around marriage would agree that individuals are most vulnerable, and intimate with others, when sex is a question. The ‘answer’ to that vulnerability includes pleasure and pain, but never full knowledge of anyone or anything.

The baker’s naming of “the Bible” as his moral authority, like the language and aspirations of marriage equality in Collins’s story of Phariss and Holmes, ignores the precarity of the sexual within any one relationship. The queer critique of marriage also falls into the same easy logic of a conflict defined by the defenders and destroyers of marriage. And for all its good in winning marriage equality, the use of the melodramatic mode has tended to obscure the ceremonial purpose of marriage. No mere celebration of love, marriage is a public witnessing to the precarity of the sexual bond and the nexus of trust that holds it together. Every side of the debate around marriage would agree that individuals are most vulnerable, and intimate with others, when sex is a question. The ‘answer’ to that vulnerability includes pleasure and pain, but never full knowledge of anyone or anything. To let the meaning of the sexual bond hinge on the production of a baby or to think marriage requires monogamy are both coverups for the feelings of human vulnerability. What the baker at Masterpiece Cakeshop misses in his own coverup reading of “the Bible” is how, long before the marriage-equality movement, Christian communities have felt it necessary to publicly witness and recognize the foundational social place and power of a sexualized commitment between partners of the same sex.[2] These relationships were sexualized in the very question of their coming together, answerable by no other people than themselves and God. To attest to know more than those parties is to demean religion itself.

Melodrama, which has included its fair share of claims for divine knowledge, can draw our attention to the categorizations people employ when they have no sure ground to stand on. But, in its highest forms, it can also portray the guessing and the twists and turns they put themselves in along the way, including those within a relationship. Alas, none of the writers reviewed here are interested in this level of emotional nuance. We are left with flat, one-sided voices that are ultimately unthinking. ‘Principled’ rejection of same-sex marriage is predictable in that world. So are the now stock melodramatic characters of the person who is driven to marry by their attraction to its commodified celebration or the person who sees the financial and medical security it brings as simply an addendum to their own personal commitment to a romantic partner.

Here it is necessary for me to be melodramatic. In the choice for marriage is the admittance to the vulnerabilities that bring us together and the acknowledgment of the precarity of the bonds that hold us there. Since the public event of marriage is the most salient recognition of that reality in contemporary society, there should only be more cakes and ale to preserve it.