“There is probably no subject more important than the study of food.”

—George Washington Carver

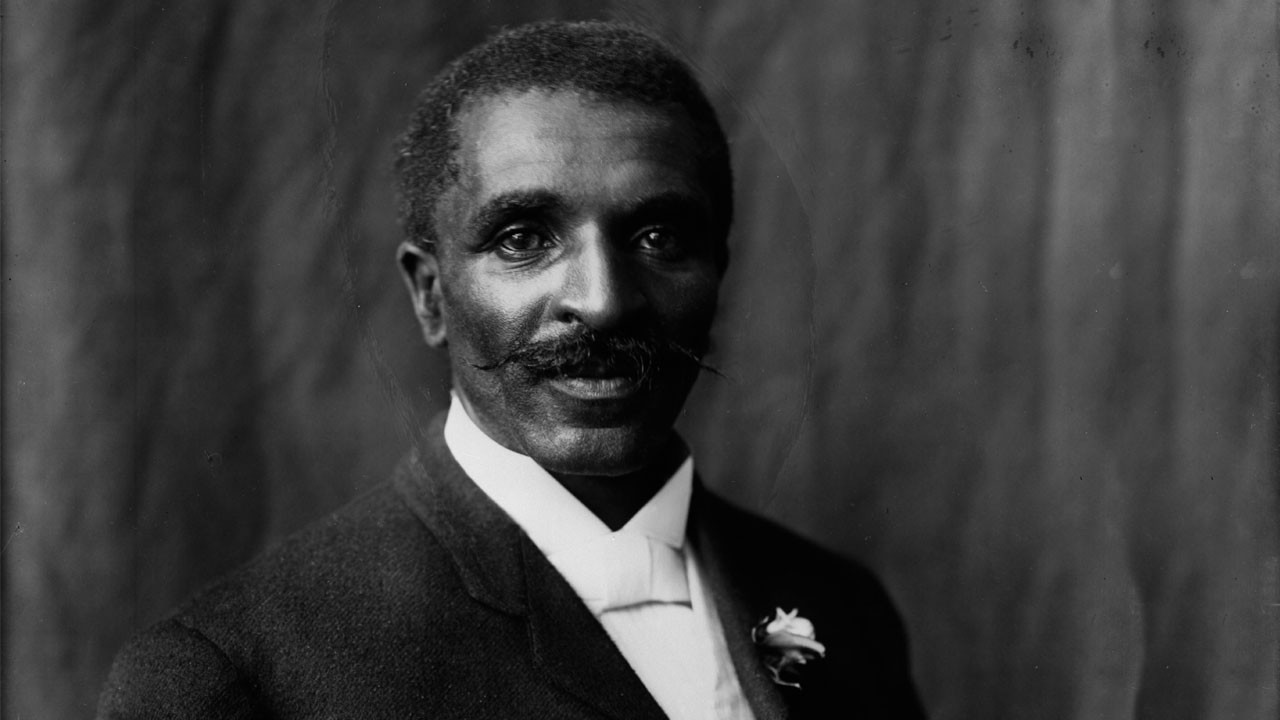

“When just a mere tot … my very soul thirsted for an education … I wanted to know every strange stone, flowers, insect, bird, or beast. No one could tell me [what I wanted to know],” Carver wrote in his autobiography. From his early experiences as a former slave searching for education in his native Missouri, to his unprecedented achievement of a master’s of science in Botany from Iowa State, to his long academic tenure at Tuskegee in the heart of the segregated South, George Washington Carver was determined to access the education and career that most white Americans would have denied him. Although his position as a highly educated black man at the end of the 19th century could have led him in a number of directions, including a permanent faculty position at Iowa State, Carver believed that God and his race led him generally to the South and specifically to Macon County, Alabama. The boy from Missouri may have had a long path to faculty member at the renowned Tuskegee Institute, but his zeal for knowledge of the natural world and determination to improve the lives of the everyday black farmer never flagged.

Carver can most accurately be referred to as a botanist, if one whose domain extended beyond the discovery and categorization of plant species. He recalls his almost inchoate boyhood affection for his wild and tended plants, calling them his “pets” and noting that at the time neighbors called him “the plant doctor” he “could hardly read.” Such beginnings led historian Linda McMurry, in her 1981 book George Washington Carver: Scientist and Symbol, to analyze his stature as both “scientist and symbol” and to address the potent mythography which still swirls around the man. More recently environmental historian Mark Hersey, in his 2011 book My Work is That of Conservation: An Environmental Biography of George Washington Carver, has further explored Carver’s legacy, celebrating him as a conservationist whose race and Christian spirituality have contributed to his being omitted from studies of early 20th century naturalists. To call Carver a civil rights activist who focused on food, in the way of an Anne Moody, author of the memoir Coming of Age in Mississippi, may be revealing, but is also incomplete. Carver’s career most certainly led to an increased belief in black intellect and scientific prowess; his life constituted its own, if indirect, debunking of white superiority. Yet while Tuskegee’s plant scientist was publicly reticent on the subject of civil rights, much in the way of his employer Booker T. Washington, he nonetheless promoted racial harmony through his Christian affiliations, via his willingness to take on speaking engagements with white schools and institutions, and through his work with white businessmen and politicians. Rather than view Carver from a specific and single perspective, I would like to add another perspective to the portrait of a black professor and scientist—that of an early proponent of what we now call sustainable agriculture and farm-to-table eating. (Today’s acolytes of farm-to-table dining tend to be gastronomic elites seeking out the latest iterations of haute cuisine; Carver’s writings urged rural agriculturalists to rely on their own productions, rather than purchases from a store.) The self-reliant ideology of charismatic educator and influential race leader Booker T. Washington, founder and first president of the Tuskegee Institute, would find one of its mission’s most successful proponents in the Iowa-trained botanist.

Carver’s childhood was unusual for one born into slavery: After losing both his parents while a small child, he was raised by his former owners, the Carvers. In some ways he was treated almost as a foster son, albeit one with the limitations of being born of black parentage. While his brother James, also raised by Moses and Susan Carver, was “tall, robust, and husky” (McMurray, 13) and later worked as their “hired labor” until shortly before his death from smallpox, George was from an early age “frail and sickly” and possibly tubercular. Because of his health problems, the younger Carver spent much of his time outdoors exploring small creatures and plants rather than logging or haying: “I literally lived in the woods.” Susan Carver assigned the child various household tasks including cooking and crocheting. These skills would later prove crucial when he moved from place to place in search of an advanced education, for segregation prevented him from attending many schools. He ended up as another foster child of sorts, most notably to the black couple Mariah and Andrew Watkins. Mariah Watkins’s reputed “good knowledge of medicinal herbs” and culinary skills furthered Carver’s interest in plants as well as in the methods of preparing them for human consumption and medical applications. His desire for further education led him from the home, and this time Carver cooked for a living. In a manuscript dated 1897, the botanist noted that in his teens he “was cooking for a wealthy family in Ft. Scott Kansas for my board, clothes and school privileges;” not long afterwards, Carver worked “as head cook in a large hotel” in Winterset Iowa. After being refused admission on racial grounds at a school in Kansas, Carver continued supporting himself with his domestic skills; his entrepreneurship included running laundry services, the latter of which would enable him to provide himself with room and board at Simpson College and then at Iowa State. These experiences, especially his stints as cook, undoubtedly account for his incorporation of household hints, recipes and cooking suggestions in the publications he would later write. Like Robert Roberts, the noted African-American butler and author of The House Servant’s Directory (1827), and others before him, Carver used his skills in service to augment a later career; in his case, his “cookbooks” were sponsored by the powerful Tuskegee Institute.

Eat local and organic may be the rallying cry today, but in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Carver saw that path as not only fiscally prudent, but environmentally sound. Hence the Tuskegee bulletins advocated sensible and affordable farming methods, along with literally hundreds of recipes.

Carver arrived in Tuskegee, Alabama in 1896 after receiving his master’s degree in scientific agriculture from Iowa State. He would spend his entire academic life at the Tuskegee Institute, where at the zenith of Carver’s career and due to the reign of its charismatic and devoted founder, the aforementioned Booker T. Washington, the school was perhaps the most renowned historically black college in the world. (Tuskegee’s international status was confirmed by the German government’s seeking out its agricultural department’s expertise in its cotton growing endeavors in the then colony of Togo.) As he confessed during the epistolary exchange with Washington that led to his hire, “I expect … to go to my people and I have been looking for some time at Tuskegee with favor.” Like that of Tuskegee’s founder, Carver’s life and career would become inextricably linked with the institution. His eccentricities, too, would become part of campus lore—like his daily donning of a fresh flower boutonnière, his climbing the fire escape to his apartment in the girls’ dormitory building, and his habit of knitting his own socks. Carver would also wear and repair his own clothes until they were close to rags, often refusing gifts of attire: biographer Rackham Holt stated that Carver wore the same suit to the 1937 unveiling of his commemorative bust at Tuskegee that he did for his graduation from Iowa State.) Washington hired Carver to run the agriculture department. Thus the botanist spent some of his early career running the campus poultry farm, attempting to start an apiary, and even launching a trial silkworm colony. Unfortunately, Carver’s lacked the executive aptitude to flourish in academic administration and animal husbandry: The high mortality rate of the school’s chickens, to name just one incident that led to a high-level donnybrook, drew criticism from Washington and eventually led to Carver’s dismissal from his poultry duties. As interested in research as teaching, Carver’s view of his trajectory at Tuskegee differed from Washington’s plans; he did not yearn to be a dean or campus administrator. One can reasonably state that Carver’s professional relationship with Washington was turbulent. Nevertheless, when Washington died before reaching his sixtieth birthday, the botanist rued the many times the two had exchanged words.

Despite their differences, Carver and Washington admired the other’s abilities and would have admitted that the other’s celebrity positively impacted his own life’s work—although that did not stop Carver from threatening on more than one occasion, as star faculty are wont to do, to take his professorship elsewhere. Carver’s fame, then and now, frequently is laid at the door of the many experiments he performed leading to new and surprising uses for common agricultural products like peanuts and sweet potatoes. Overlooked in the celebration of his entrepreneurial science is the impetus for his move to the Deep South: his desire to become a race man by aiding the farmers who labored ceaselessly with little to show for their efforts but debt. Carver’s significance should not solely be accounted for by his creation of multiple new uses for agricultural crops. In a nation today roiled by debates over genetically modified organisms (GMO food crops), Carver’s “old fashioned” methods of composting, kitchen gardens, and conscious eating seem simultaneously quaint and prescient. He should rightly be lauded as an avatar of responsible land stewardship and healthy eating.

At Tuskegee industrial education ruled the day, and so teaching was intended to be a major component of Carver’s duties. That said, classroom teaching eventually took a back seat to his research and public presentations; his disinterest in administrative details possibly spilled over into a dislike for the minutiae of grade books. Nonetheless he displayed an Emersonian belief in the natural world as an extension of, if not a replacement for, the classroom. His 1910 bulletin Nature Study and Gardening for Rural Schools lays out his experiential approach to education, which included at Tuskegee having his classes compete with one another in collecting specimens. Students were amazed by their professor’s ability to identify seemingly everything brought to his attention. Other of his notable pedagogical successes were conducted through outreach efforts like appearances at state fairs and farm visits, for what we know today as the agricultural extension movement was just getting underway. Remarkably, and due to Washington’s canny and determined efforts, Tuskegee was granted agricultural extension school status in 1897 despite being neither a land grant college nor an institution serving whites. Starting in 1898, as part of Tuskegee’s extension efforts, Carver authored and published numerous bulletins, which were circulated gratis to the small farmer, as part of the school’s educational mission; two to five thousand copies comprised initial print runs. [1] In addition to offering instructions on such topics as growing cotton successfully on sandy soils, and the expected offering of a historically black school in the cotton belt, Carver’s pamphlets laid out instructions for raising, preserving, and preparing the fruits and vegetables from the gardens of the black Southerners whose lives he worked so diligently to improve. Carver’s efforts included suggesting to his audience how to use organic methods when cultivating fruit and vegetables, and the multiple reasons to do so, as well as instructing his readers in methods of cooking, preserving, and eating homegrown produce. Eat local and organic may be the rallying cry today, but in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Carver saw that path as not only fiscally prudent, but environmentally sound. Hence the Tuskegee bulletins advocated sensible and affordable farming methods, along with literally hundreds of recipes.

Unlike his contemporary Rufus L. Estes, the black Pullman chef whose expertise in the kitchen and facility with customer service brought him a measure of fame as a cookbook author, Carver was not writing a cookbook for those who had sampled his dining car dainties. Instead, Carver’s bulletins for the average farming family were aimed at people unlikely to serve in a Pullman car, much less emulate the menus at the Pullman’s famed dinner tables. Carver’s recipes for homey fare were delivered either in a paragraph in which the ingredients and instructions are iterated or in the modern style that begins with a listing of ingredients and then proceeds to the how-to. Some foods he deemed so versatile (or perhaps the demand called for repeated publications) multiple bulletins on the same crop were offered. The prosaic cow pea received four bulletin treatments, with Carver suggesting everyday dishes such as “creamed peas,” “Alabama baked peas,” or “hopping john.” A true booster, Carver averred that cow peas should take their place in gastronomic lore along with more highly regarded legumes such as the “White, Soup, Navy or Boston Bean.”

Three Delicious Meals Every Day for the Farmer (Bulletin #32, 1916) offers an attractive dining experience for those often thought to be uninterested, or unable to afford, such meals. Well ahead of the curve of the now legion numbers of farm-to-table adherents and hobby gardeners who put up sauerkraut from backyard plots and raise urban chickens, Carver opens with a gentle scolding—“we are wasteful … Ignorance in the kitchen is one of the worst curses that ever affected humanity.” Much in keeping with earlier, vegetarian adherents such as William Alcott and Alexander Graham, Carver warns against the “bad preparation” of meals and the perils of “bad combinations” of food. The botanist lauds the healthy and “medicinal value … when wisely prepared” of homegrown fruits and vegetables, and includes a week’s worth of menus that include such dishes as sliced tomato and onions, green corn fritters, and homemade sausage. Certain recipes do include pork fat or bacon, but also represented are vegetarian dishes such as tomato soup, nut sandwiches, and creamed peas. The meals are advertised “every day” and “delicious” in large measure because the cook’s ingredients are culled from the farm’s own kitchen garden or perhaps obtained by local bartering Carver knew that locally grown foods prepared in the farmer’s kitchen would be healthier and less expensive that store-bought goods which provided a fraction of the nutritional value at a much higher cost. Carver’s desire to bring self-sufficiency and tasty meals to the struggling agricultural worker was in its way every bit as revolutionary and creative as his famed experiments that led to such products as peanut-hull-based wallboard. He understood that a black farmer’s planting cotton on every available scrap of land increased the chances that the farmer would remain in poverty, not decrease the likelihood of it. “Carver conducted agricultural research to make black farmers economically independent, producing their own means of subsistence and ending their dependence on the cotton industry.” (Zimmerman, Andrew; Alabama in Africa: Booker T. Washington, the German Empire, and the globalization of the new South. Princeton UP, 2010, 22). While Carver understood commercial fertilizer to be an occasional necessity, he also knew—and demonstrated—that the proper use of forest and farm compost could work just as well, if not better, to reinvigorate worn-out soils. But “Few contemporaries grasped what he was really trying to say or do” (McMurray, 308) Journalists of the time found publicizing business opportunities more newsworthy than saving the small farmer. If “Small-scale, simple technology that could be practiced by a black sharecropper was overshadowed by the lure of mass production technology” (McMurray, 306), so too was Carver’s advocacy on behalf of kitchen gardens and home-cooked meals.

The extent of Carver’s food and nutritional activism may remain unknown. Few records from the earliest years of Carver’s career exist, as a 1947 fire in the Carver Library destroyed much of the material extant before 1920. His own writings give little detail about his culinary experiences. (The 1943 biography by Rackham Holt, based on numerous conversations with Carver, includes many anecdotes based on memories of decades-old events). How can we fully assess Carver’s impact on food beyond what is available in the archive and Tuskegee publications? More specifically, how could he reach the farmer who could not access the information printed in the bulletins because he or she could not read? One clue may lie in the Jesup Wagon, named by Booker T. Washington for the financier who funded Tuskegee’s extension school on wheels.

The Jesup Wagon, a prototype of which Carver used to bring his exhibits into the Tuskegee community. Illustration: Courtesy of Tuskegee University

The illustration reveals the scientist’s early training and facility in art. Although Carver did not personally staff the Jesup Wagon—that role would be assumed by Thomas Campbell—he accompanied its prototype into the community. Thomas Campbell, Carver’s former student who later led the Jesup Wagon’s excursions (and was the FDA’s first black extension agent), recalled “in those earl[iest] years it was Dr. Carver’s custom, in addition to his regular work, to put a few tools and demonstration exhibits in a buggy and set out … to visit rural areas near Tuskegee. … he would give practical demonstrations, both varied and seasonal;” rather than wait for farmers to visit the extension station Carver went to them. In current terminology, his was a “pop-up” agricultural school. His educational vision encompassed a classroom on wheels that would include advice on healthful eating as well as agricultural methods. Because these rolling schools meant to educate the farmer and his wife, demonstrations illustrating the proper use of agricultural tools and ones covering the healthful preparation of food were presented together.[2] The Jesup Wagon and its predecessor thus aimed at all farmers, whether educated, illiterate, or someone in between. (Low literacy rates kept many farmers from utilizing the wealth of information contained in Carver’s pamphlets, a situation Carver lamented.) If Carver’s bulletins for Tuskegee—sought after by whites as well as blacks—provided a literal script for self-reliance and dignified living accompanied by recipes within the reach of modest but aspiring households, these vehicular classrooms could serve a similar purpose.

Carver’s extracurricular, out-of-doors work on behalf of the small farmer, like the pithy advice of the bulletins, has been overlooked if not disregarded entirely. “Organic fertilization … answer[ed] a crying need for small farmers” (McMurray, 90), and Carver explained the how-tos of that method, even though he did not reject a judicial use of commercial fertilizers. Nonetheless, the poorest farmer could scarcely get out of debt let alone purchase the chemical products said to increase agricultural yields. To “cast down one’s bucket where one stands,” to pull up decaying organic matter rather than fresh water (as in the parable Washington recounted in his famous 1895 Atlanta Cotton States and International Exposition Speech), was wise advice on several levels. Still, Carver’s “faith in organic fertilization placed him outside of then current scientific doctrine” and so to achieve his larger goal of assisting the black farmer, Carver played to the business and political interests that lauded him as a “cook stove chemist.” That his inventions and creations could be monetized or at least deployed as advertisements for regional “progress” could redound to the benefit of his people. (McMurray, 90) These goals—helping the small farmer by advocating self-sufficiency and supporting agribusiness—appear at odds. It was Carver’s hope that his renown in the business and political sphere would pay dividends to rural blacks in one way or another. From Washington’s era until the present day, critics have said that the Tuskegee doctrine of self-sufficiency countermanded much of the rhetoric of modernization. Carver’s peer W.E.B. Du Bois urged higher education and professionalization as key to gaining civil rights and self-respect, an uplifting of the peasant class, or those with the abilities to rise, into the twentieth century. Washington’s fears of modernization stemmed from the concern that the black peasantry would become an unskilled class of consumers. Consumerism per se ran the risk of making blacks highly dependent—which of course is precisely what happened on the farms when blacks relied on store-bought food. For someone like Washington, a liberal arts education of the sort that Du Bois preached threatened to produce a highly cultivated consumer class that would only feel entitled to be an elite but could not take care of its own needs. Yet Washington also said that while a community may not need someone that moment who can parse Greek, they would need someone who would fix wagons—and that having those wagons, and a higher standard of living, could eventually lead to requests for Greek instruction.

Rather than purchase canned goods, meat, and dairy from local grocers, Carver instructed, that the farmer should practice self-reliance; it was a theme sounded regularly through the three-plus decades Carver published the Tuskegee pamphlets. In his preface to The Canning and Preserving of Fruits and Vegetables in the Home, Washington “endorse[d] all that Professor Carver has said … and [I] urge colored farmers throughout Macon County to put into practice what he has suggested.” Carver began this particular bulletin by noting that “fully two-thirds of our fruit and tons of vegetables go to waste” and tempted his readers with “delicious” peach or strawberry dried-fruit “leather,” to name but one of his simple and electricity-free methods of preserving food. His guidelines would enable the small farmer to preserve foods for eating throughout the year. Carver continued his encomia to culinary freedom in bulletins like How to Grow the Tomato, in which he not only gave recipes for fresh tomato dishes but also for preserves. Bulletins even gave instructions for preparing pantry staples such as flour and mock “cocoanut.” Then as now, Carver’s instructions were useful for those living off the grid—and those who had yet to access public utilities. Today, thanks to the Internet, a complete listing of Carver bulletins is easily accessible online.

Those following the trend towards modern foraging would appreciate that Carver did not limit his advice to domesticated fruits and vegetables, pointing his readers to the bounty around them free for the taking. In 43 Ways to Save the Wild Plum Crop Carver goes further, lamenting the foods free for foraging that go unused annually: “I feel safe in saying that in Macon County [Alabama] alone there are many hundreds of bushels of plums that go to waste every year.” The wild plum provided delicious material for pies and soups, Carver pointed out, suggesting “no fruit makes more delicious jams, jellies, preserves, marmalades, etc.” He furthermore urged his readers to try a number of appealing recipes, including some for mock olives, catsup, and “Plum Lozenges (Very Fine).” Along with his editorials—“very fine” or “delicious” were often appended as suffixes to recipe titles, much in the way that the better-known Irma Rombauer of Joy of Cooking (1931) fame would add “cockaigne” to dishes she particularly liked—he would occasionally suggest ways to plate, as in his injunction to “decorate [this dish] artistically with nut kernels.”

The wild plum would be an obvious delicacy to anyone walking through a southeastern forest, as would other of the larger wild fruits, such as persimmons. Carver did not stop with the most noticeable edibles that could be foraged, however. In his World War II-era bulletin titled, “Nature’s Garden for Victory and Peace” (Bulletin #43, 1942)—the reference to victory gardens is unmistakable—Carver gives the publication an epigraph, a four-stanza poem by popular poet Martha Martin, “The Weed’s Philosophy.” In this verse an anthropomorphized weed laments its outcast status in a world that would destroy it: “If a purpose divine is in all things decreed/Then there must be some benefit from me a—weed!” In the original version, included in The Weed’s Philosophy and Other Poems, the second line does not end with an exclamation point. That Carver wishes to emphasize the beneficial nature of the unwanted plant becomes clear when he next cites the publication of a 1942 article in the Alabama Journal titled “Don’t Worry if War Causes Green Vegetable Shortage, Weeds Are Good To Eat,” and the subsequent letters that come to his attention asking if this claim has merit. Carver goes on to discuss a number of such “weeds,” from dandelions to purslane and lamb’s quarters.[3] Illustrated with several of his own botanical drawings.[4] Donning his chef’s toque, the botanist gives general instructions for serving and cooking various greens; the most formal recipe describes a classic dandelion salad, augmented with chopped radishes, onion, and parsley, and garnished with pickled beets and hard-boiled eggs. He closes with the hope that everyone will make these wild delicacies part of an everyday diet, as long as these foods are in season. Those reared on the advice of back-to-nature guru Euell Gibbons, whose foraging handbooks shot to counterculture fame in the 1960s, should know that he had a precursor on the faculty of Tuskegee.

Foraging for wild foods was part of Carver’s legacy, or rather a legacy with which contemporary students of foodways and counterculture eating habits are familiar—even if they do not trace its antecedents back to Tuskegee. Carver’s suggestions on turning towards wild plants to add healthy and thrifty meals to the rural black American’s diet had been preceded by his urgings to look to one’s own homestead in an earlier war-time publication, “Twelve Ways to Meet the New Economic Conditions in the South” (1917) and revisited ten years later in “How to Make and Save Money on the Farm” (Bulletin #39). Meant as guides for farmers struggling with the depredations of the boll weevil, by the tyranny of cotton monoculture with the subsequent depletion of the soil, and the seeming inability of most farmers, renters or owners, to get ahead financially, Carver wrote his booklets in a question-and-answer format. Presented as twelve questions that small farmers were likely to pose, the queries were followed by practical advice indicating that workable solutions could be reached by the farmer’s ingenuity and planning; the pamphlet also included tips that went beyond utilitarian instructions. Beginning with suggestions for avoiding the worst of the boll weevil’s destructive impact, Carver went on to describe how the cash-strapped farmer could still fertilize soil worn out by repeated cotton cropping—he notes how successful the demonstration plot at Tuskegee has been through the practice of compost application and crop rotation, should consider keeping a small number of domesticated animals (e.g., a cow, a few chickens), and have a garden and fruit trees. The farmer “can realize more money [from a variety of crops such as corn, peanuts, and sweet potatoes] than from cotton;” he furthermore asserts that even if a “paying market cannot be had for the raw product, they should be fed to stock, and turned into milk, meat, butter, eggs, lard, etc.” Even sharecroppers and renters should pursue these suggestions, as “It will leave more money in your pockets, aside from the great value of forming correct habits of living.” The later bulletin includes numerous recipes culled from other Tuskegee bulletins, repeating, to take one example, the directions for drying and preserving pumpkins for later use (in this particular case Carver repeated preservation techniques outlined in his 1915 Bulletin # 27, “When, What and How to Can and Preserve Fruits and Vegetables in the Home.”

Donning his chef’s toque, Carver gives general instructions for serving and cooking various greens; the most formal recipe describes a classic dandelion salad, augmented with chopped radishes, onion, and parsley, and garnished with pickled beets and hard-boiled eggs.

Important to our understanding of Carver’s sense that art and science go hand in hand,[5] the botanist did not fail to recognize that hard work deserves beauty, suggesting “a pretty door-yard with flowers.” A well-landscaped home’s ability to raise the value of a property is important, he avers, but notes that rather than a physician sometimes “all we need is a bunch of beautiful flowers from loving hands.” The botanist may be a professor of agricultural science but he was also an artist, and anticipated Alice Walker’s recognition of how her mother’s beautiful flower beds eased the struggle of their family: “Because of her creativity with her flowers, even my memories of poverty are seen through a screen of blooms—sunflowers, petunias, roses, dahlias, forsythia, spirea, delphiniums, verbena.” Tomato cultivation, Carver asserted, went beyond nutrition alone: “There are so many sizes, colors and varieties that, for garnishings, fancy soups, and especially fine decorative table effects, they are almost indispensable.”

The life and career of George Washington Carver, known to generations of Americans as the peanut man, has been overdue for reassessment. Carver’s calls to the impoverished black farmer to eschew commodity foods and to dine well from the products of his own and neighbor’s plots, not only resonate in today’s lifestyle pages but also with the cries of public health and agricultural activists calling for the labeling of GM food and greater access for the poor to unprocessed food and greater encouragement for them to develop a healthier diet. Will Allen, recognized for his work in urban farming with a MacArthur Fellowship “Genius Grant” award, may be better known to today’s foodies as the black man who brought fruits and vegetables to the impoverished African American, but the noted urban farm activist gives Carver a shout-out as his inspiration and predecessor, even including Carver’s illustration of the Jesup Wagon in his memoir. “I was not the first African-American farmer and teacher to make trips through the South to teach people how to farm. The educator and agriculturalist George Washington Carver has long served as an inspiration to me. … My workshops at Growing Power were in the spirit of Carver’s own [lessons]” (Allen, 210).[6] Perhaps we should not be surprised that Rodale Press’s first issue of Organic Gardening appeared in the last year of George Washington Carver’s life, 1943. Carver’s baton was ready to be passed, even if decades would follow before his advocacy would be recognized.